Understanding Implicit IRRs: The Core of Rational Investing

When you buy shares in a company, the price you pay carries an implicit Internal Rate of Return (IRR). Essentially, anyone who purchases shares—and is willing to hold them indefinitely—locks in a certain IRR, determined by two factors: (i) the price paid and (ii) all future cash flows the company will provide to its owners. These returns typically come either as dividends or as a lump sum (usually cash) if the company gets acquired.

This concept applies universally to all companies—even those operating in sectors like technology, where expectations for rapid sales and margin growth are common. However, because shares can be traded easily and frequently, investors often mistakenly focus on market timing. In reality, collectively, investors always end up receiving the IRR described above—someone is always holding shares of each publicly traded company.

From my experience—supported by extensive data and proprietary tools(*)—the Market does attempt to value companies based on their future cash flow prospects. It isn’t just a random walk detached from fundamentals. Yet, the Market suffers from short-term bias: it tends to overly emphasize current earnings, causing prices to fluctuate far more than they would if investors consistently took into account earnings across full economic and industry cycles.

This short-term bias creates opportunities for active portfolio management. By carefully selecting investments based on long-term cash flow potential rather than short-term earnings fluctuations, we aim not only for strong long-term returns but also for the comfort of knowing our investments are fundamentally sound—backed by real cash flows rather than speculative hopes that someone else will pay more later.

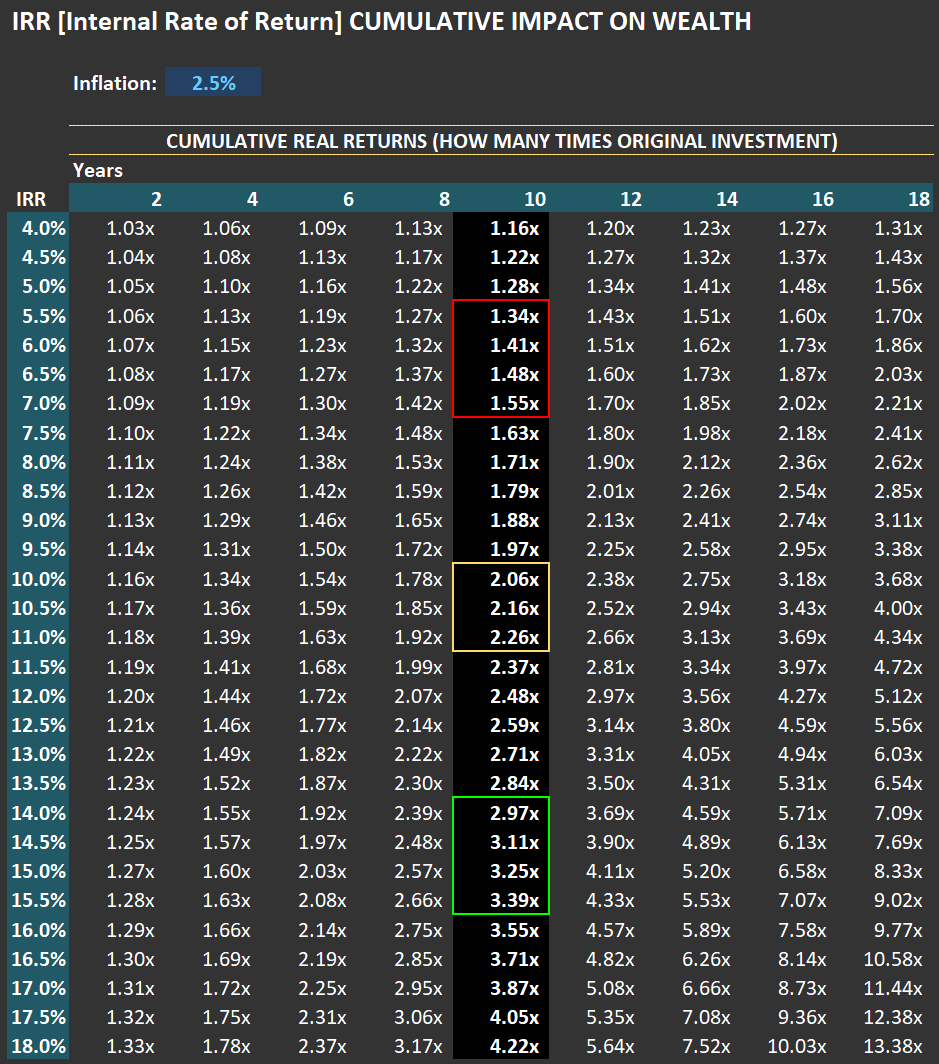

Every company entering RIM’s portfolio on the long side has an “above normal” expected IRR, while those on the short side have “below normal” expected IRRs. To illustrate what “normal” looks like within RIM’s Circle of Competence (CofC), see the table below. It shows cumulative real returns—how many times your initial investment would grow—after a given number of years based on the observed IRR at purchase.

I’ve selected the 10-year mark as a practical proxy for “long term.” For instance, if you bought something today with an implied IRR between 10% and 11%, after ten years, your investment would grow—in real terms—to between 2.06x and 2.26x your original investment (highlighted in yellow). This range represents the average observed returns over very long cycles (20+ years) for companies within RIM’s CofC.

The green box highlights the typical IRRs (14% to 15.5%) at which we initiate long positions. Conversely, the red box shows typical IRRs (5.5% to 7%) at which we initiate shorts. In practical terms, when RIM initiates a long position in a company, we expect cumulative dividends (and/or cash payment for the business) equivalent to roughly 3.2x our initial investment; shorts typically offer only about 1.4x—a significant 120% difference in expected returns.

Ultimately, regardless of personal hopes or beliefs, the Market collectively prices companies based on expected future cash flows available to shareholders. Therefore, successfully investing requires both skill and discipline: skill in accurately forecasting long-term earnings prospects and discipline in buying when earnings—and thus prices—are unusually low (and shorting when they’re unusually high). This disciplined approach is precisely what I practice every day at RIM.

(*) My insights are built upon 67 detailed valuation models I’ve meticulously developed and refined over the past two decades. Additionally, I rely heavily on Odysseus—RIM’s custom-built portfolio management, trading, and reporting tool—which I developed using Python and some of today’s fastest computational libraries.