Investment vs. Speculation: Why $AMZN's [Amazon] Whole Foods Deal Reveals the Difference

When Amazon announced its $13.7 billion acquisition of Whole Foods in June 2017, the market greeted it with the kind of excitement typically reserved for transformative events. Headlines proclaimed a “radical disruption” of retail. Analysts spun scenarios of Amazon dominating the grocery industry. The chatter was intoxicating—the sort of “super-fantastic” narrative that gets investors excited and stock prices buoyed. Eight years later, a great WSJ article (here) revealed some key figures for Whole Foods. They now operate 547 stores and employ 106,000 people. It’s time to ask a more grounded question: What did Amazon actually get for its money? This is where the distinction between speculation and investment becomes crystal clear.

The Difference Between Betting on a Story and Buying a Business

Speculation is what happens when someone hears “Amazon is buying a grocer” and immediately imagines Amazon cornering the entire grocery market, margins expanding magically, and hypercompetitive Walmart getting crushed. These narratives feel plausible. They’re seductive. They create urgency. But they’re built on imagination, not analysis.

Investment is different. It involves doing the unglamorous work of understanding what you’re actually buying. In the case of Whole Foods, that means understanding historical store productivity, typical operating margins in the organic grocery space, and whether a premium grocer can realistically achieve transformational growth in a mature, hypercompetitive market. It means calculating what return the price paid actually implies—and asking whether that return justifies the risk.

What the Numbers Suggest

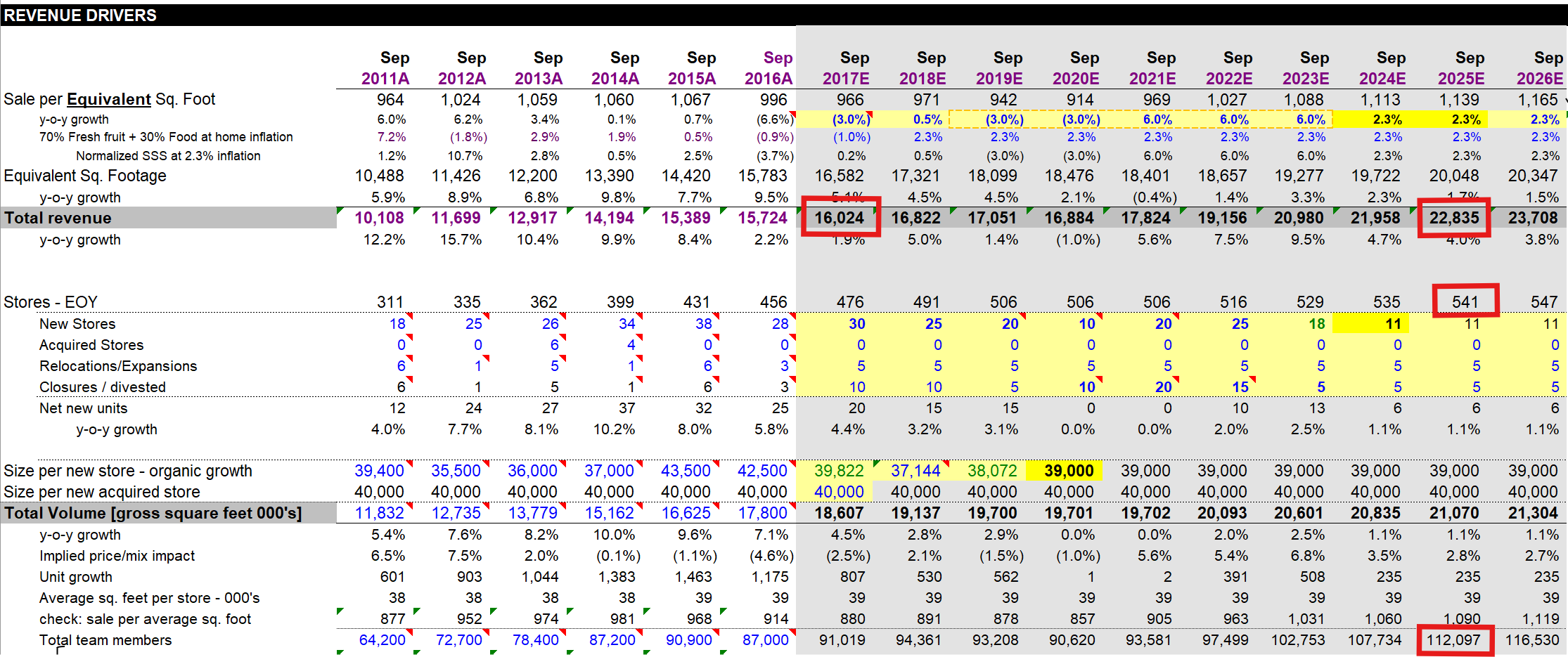

Back in June 2017, I made my last update on my model of Whole Foods - I had been following the company for years (see first picture below - relevant figures highlighted by red rectangles). That model projected where the company would be in the ensuing years. The results, which have now been partially validated by eight years of reality, are instructive.

On store count, my forecast proved remarkably prescient: I projected 541 stores by September 2025; the company now operates 547. On headcount, I forecasted 112,000 employees; the current figure stands at 106,000. On sales, I modeled total growth of 42% from 2017 to 2025; Amazon reported more than 40% sales growth since the acquisition. These aren’t accidents. They reflect the reality that Whole Foods operates in a mature business in which productivity per square foot, per employee, and per store tends to fall within predictable boundaries.

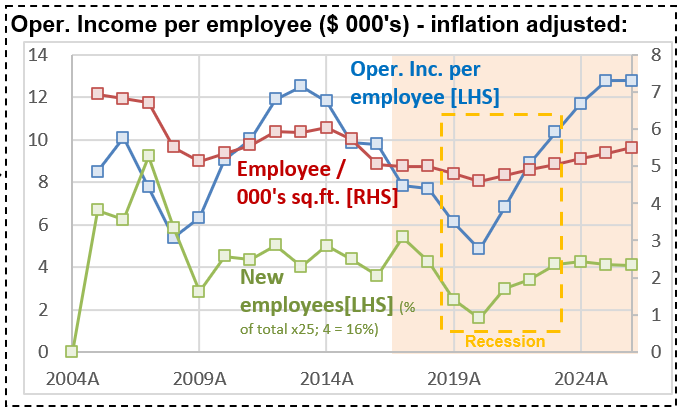

But here’s what’s remarkable: these projections also revealed something uncomfortable. When I calculated the Internal Rate of Return (IRR) that Amazon achieved on its Whole Foods investment—assuming the company’s margins remain consistent with historical patterns—the IRR comes in at approximately 8.8%. And by “historical patterns,” I meant reaching an operating profit per employee consistent with times when the company was operating very efficiently (see second chart - focus on the blue line).

Why 8.8% Should Matter

Eight point eight percent is a respectable return in many contexts. It’s better than Treasury bonds. It beats inflation. But for Amazon—a company that commands extraordinary capital and pricing power, with a cost of capital (Ke) that reflects its dominant market position—8.8% is mediocre. It’s below the historical hurdle rates that truly accretive acquisitions typically exceed.

To put it another way: Amazon paid $13.7 billion for a business that, if it performed exactly as my 2017 model suggested (and the evidence suggests it has), would compound capital at a rate that fails to fully reflect the premium one should demand for deploying that much capital in such a capital-intensive, hypercompetitive industry.

This doesn’t mean the deal was a disaster. Amazon hasn’t destroyed value. But it hasn’t also created the spectacular value-creation story that the initial narrative promised. The company moved 40% more merchandise through 547 stores and 106,000 employees—an outcome you could have forecast by looking at historical productivity metrics and applying straightforward extrapolation.

The Broader Lesson

This distinction between investment and speculation explains why some investors thrive while others repeatedly lose money. Speculators heard “Amazon buys grocery” and imagined Disney-like returns. Investors asked: Given what we know about this industry, what return does this price actually imply? And if the market is correct about Amazon’s strategic brilliance here, shouldn’t the returns exceed our cost of capital? The tragedy is that poor answers to this question have led many investors into situations far worse than Amazon’s Whole Foods deal.

Take Beyond Meat, which at its peak was valued at nearly $4 billion, pricing in a future where plant-based meat would capture vast market share and command premium margins. Those who bought at peak valuation didn’t lose 30% of their capital. They lost 95%+. The difference? Beyond Meat’s valuation required speculative assumptions about market size and profitability that had virtually no historical precedent. Whole Foods, by contrast, sits in a known market with knowable economics.

What This Means for Your Investing

When you encounter a story about a company acquiring another, a new technology, or a business entering a hot new market, resist the urge to extrapolate linearly from enthusiasm. Instead, ask yourself: What is the IRR this price actually implies? Does that IRR compensate me for the risk and the opportunity cost of deploying capital elsewhere? What assumptions about margins, growth, and competitive dynamics does this valuation require? Have those assumptions been validated by history, or am I betting on a discontinuity?

For Whole Foods, Amazon’s price implied an 8.8% IRR. That’s a fact you could have calculated the day the deal closed. Everything that followed—the 40% sales growth, the store expansion, the employee base—was largely predictable, given straightforward assumptions about retail productivity. The surprise, if you were paying attention to the math rather than the narrative, wouldn’t have been that Amazon “succeeded” with Whole Foods. The surprise would have been to discover that the deal represented anything other than a competent, if uninspiring, deployment of capital into a mature, slow-growth business.

That distinction—between imagining what might happen and calculating what should happen given your purchase price—is the difference between speculation and investing. Amazon, for all its brilliance, chose the latter path on Whole Foods. And it got what 8.8% annual returns suggest you should expect: a reasonable but unremarkable business.

How This Relates to My 2017 Model

I want to emphasize something important for anyone reading this: my 2017 Whole Foods forecast was built on understanding store economics, not on believing in a transformational narrative. The model assumed:

- Whole Foods would add stores at rates consistent with past expansion plans

- Per-store productivity would remain within historical bands

- Margins would not dramatically improve (a conservative assumption, but crucial to disciplined valuation)

- Growth would be gradual, not exponential

Eight years later, nearly every projection has held. I wasn’t prescient—I was simply careful about what I assumed. And that carefulness is what separates the investors who sleep well at night from the speculators who wake up wondering where their Beyond Meat investment went.