Where Did the Cash from Operations Go?

Today, I’m diving into my analysis of $PKG (Packaging Corporation of America), a company that offers an interesting case study in how businesses deploy their cash beyond dividends and share buybacks. One common strategy is acquiring other businesses, typically within the same industry. This approach aligns with the broader trend in the U.S., a country I often refer to as “the land of oligopolies,” where many industries are dominated by a handful of major players. However, not all acquisitions are created equal—some management teams venture outside their area of expertise, attempting to diversify into uncorrelated industries. These moves frequently result in losses.

In contrast, PKG’s management opted for a more logical and focused strategy. In late 2013, they acquired Boise Inc., another paper and packaging company, for $1.3 billion. Since then, PKG has made additional acquisitions within its core industry, albeit at smaller scales.

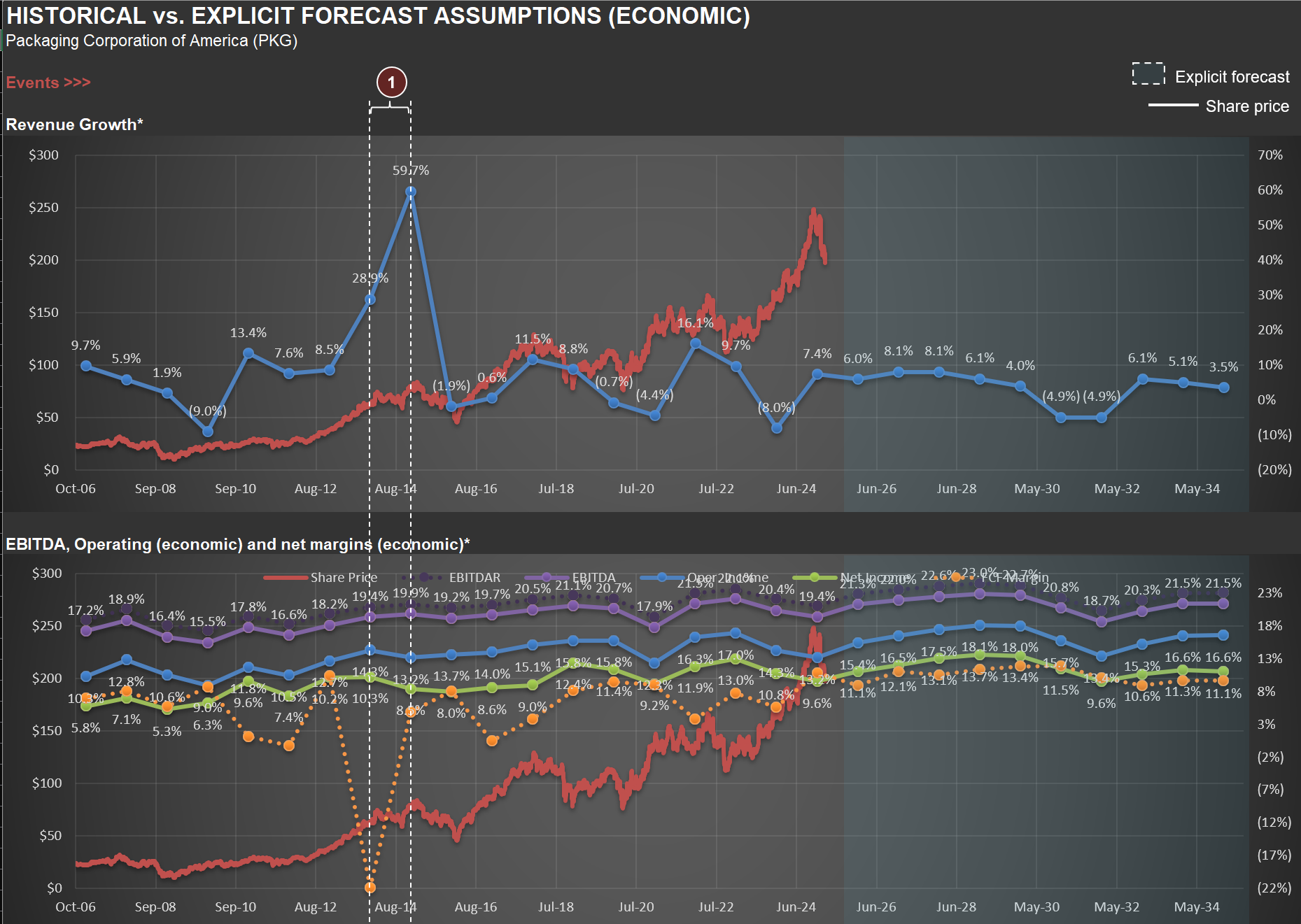

The two charts below illustrate the impact of the Boise acquisition on PKG’s financials. The first chart highlights a notable surge in sales growth over the two years following the deal’s closure. This increase reflects the integration of Boise’s sales into PKG’s financials. The second chart shows a significant negative Free Cash Flow (FCF) margin during this period. FCF margin is calculated as (i) Net Cash from Operating Activities minus (ii) Net Cash from Investing Activities, divided by (iii) Sales.

The $1.3 billion spent on Boise is captured under “Net Cash from Investing Activities” pushing the total figure into negative territory. The key question is whether this acquisition will ultimately pay off—a question that demands detailed valuation work. After assessing the rationale behind a deal, it’s essential to adjust future projections to account for the new assets and business operations.

Getting this process right increases your chances of buying or selling a company at prices aligned with your investment thesis—whether long or short. Missing critical details or skipping a robust forecast can lead to mediocre performance at best. And if you happen to make money despite a flawed forecast? Recognize it for what it is: luck.

At its core, the job of an investment manager is to minimize reliance on luck by rigorously analyzing and projecting logical outcomes. Yet even when your analysis is spot on, patience and discipline are vital—it can take years for your thesis to play out fully.