Why Valuation Always Matters: Lessons from $WMT, $KO, and $HD

During a recent conversation with an investor, he said: “I’m not concerned about the high valuation of the company I’m buying today because it’s a great company that’s growing and has good margins, and I plan to hold it for a very long time." What is your first instinct when hearing such a statement?

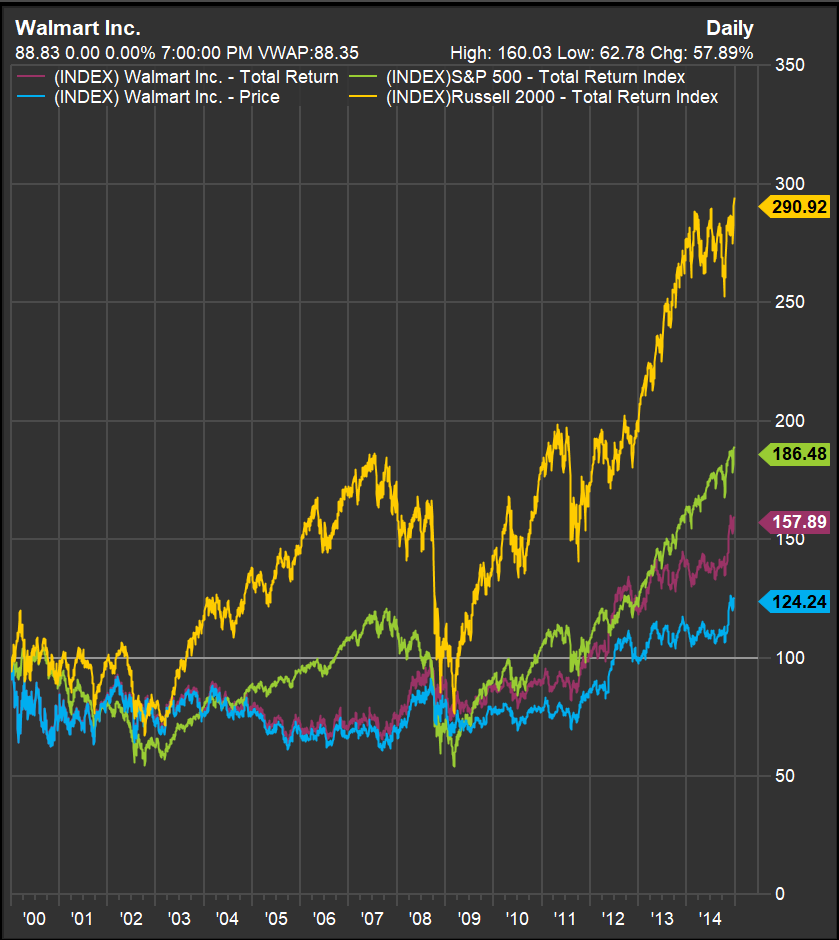

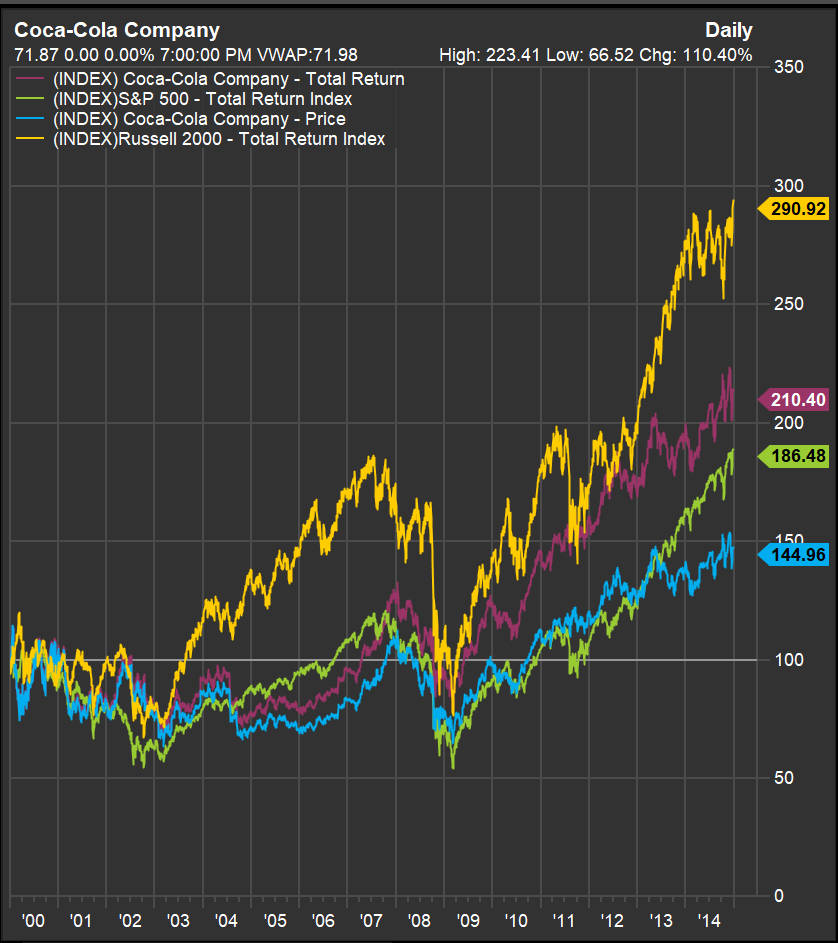

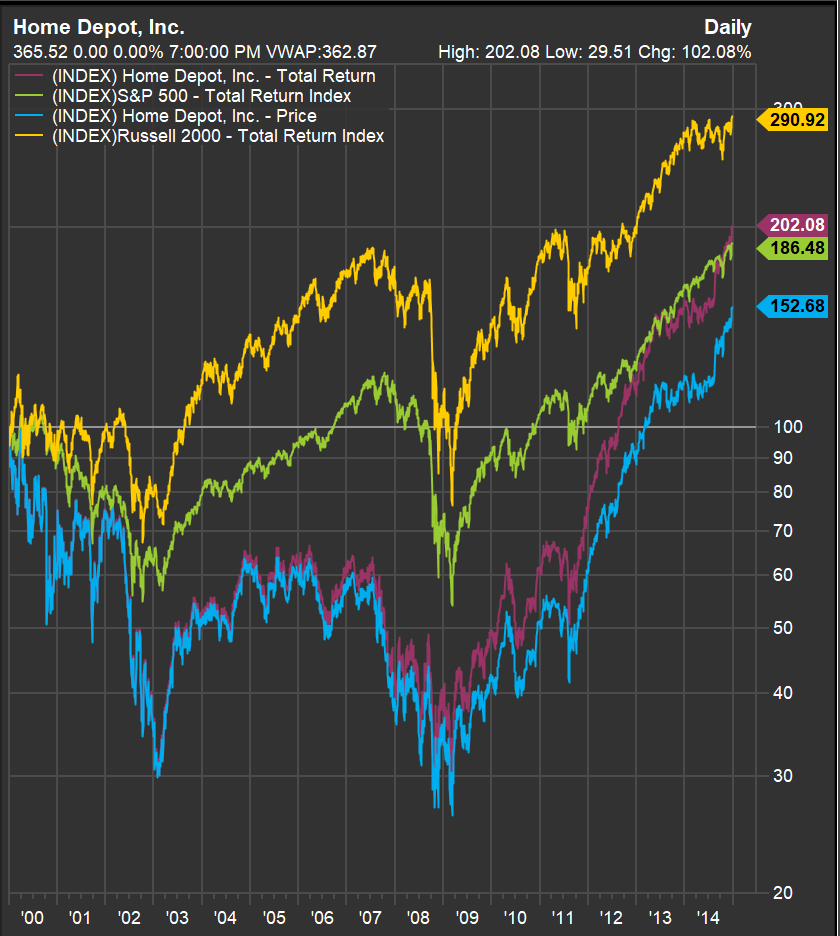

If you have doubts about whether this approach is wise, take a moment to examine the three charts below for $WMT (Walmart), $KO (Coca-Cola), and $HD (Home Depot). These charts show returns (indexed to 100 as of January 1, 2000) through December 2014—a span of 15 years. The blue line represents stock prices, but since these companies pay dividends, the “Total Return” line (red) is the one you should focus on. Two other lines are included for comparison: one in yellow for the Russell 2000 and another in green for the S&P 500. Pay close attention to how much better small, mundane companies (represented by the Russell 2000) performed compared to the broader index that participated in the bubble (the S&P 500).

The US equity market was in a bubble in 2000—a fact that hindsight makes clear. But here’s what’s curious: there was no definitive event that caused the bubble to burst in March 2000. Concerns existed, but no single trigger led to the collapse. This highlights how difficult—if not impossible—it is to predict when a bubble will pop.

What we can observe from the charts below is that each of these companies—despite their success in subsequent years in terms of sales growth, margins, and earnings—delivered poor stock performance during this period. Why? Eventually, investors evaluate their returns on investment, and if future prospects are too low relative to the price paid, share prices adjust. I’ve discussed this tendency—to seek reasonable internal rates of return (IRRs)—in this post.

Consider Walmart: around that time, its price-to-earnings ratio (P/E) ranged from 40 to 50—not unlike its recent peak above 40 times earnings. It took until late 2011—12 years—for investors to recover their money in nominal terms. Adjusted for inflation, it took even longer. Along the way, investors faced a painful drawdown of 37%.

How about Coca-Cola? Surely its stable business made it safer, right? In some ways, yes—but investors still had to wait nine and a half years to break even. While its drawdown was slightly smaller than Walmart’s (34% versus 37%), it was still significant.

And then there’s Home Depot—a case of even greater suffering due to its exposure to the housing crisis during the Great Financial Crisis (GFC). Investors didn’t recover their principal until mid-2012—a grueling wait of 13 and a half years. Worse still, they endured a staggering drawdown of 70%. How many investors could resist panic-selling under such conditions?

What ties all these stories together is one common factor: abnormally high valuations at the time of purchase. Despite these companies’ eventual growth in sales and margins—and even their ability to achieve high valuations again later—paying too much upfront led to years of poor returns and significant volatility. This brings us back to the statement at the beginning: Buy highly priced companies at your own risk. Even if their prospects are excellent, valuation matters—and it always will.