Understanding Implicit IRRs: The Core of Rational Investing

When you buy shares in a company, the price you pay carries an implicit Internal Rate of Return (IRR). Essentially, anyone who purchases shares—and is willing to hold them indefinitely—locks in a certain IRR, determined by two factors: (i) the price paid and (ii) all future cash flows the company will provide to its owners. These returns typically come either as dividends or as a lump sum (usually cash) if the company gets acquired.

This concept applies universally to all companies—even those operating in sectors like technology, where expectations for rapid sales and margin growth are common. However, because shares can be traded easily and frequently, investors often mistakenly focus on market timing. In reality, collectively, investors always end up receiving the IRR described above—someone is always holding shares of each publicly traded company.

From my experience—supported by extensive data and proprietary tools(*)—the Market does attempt to value companies based on their future cash flow prospects. It isn’t just a random walk detached from fundamentals. Yet, the Market suffers from short-term bias: it tends to overly emphasize current earnings, causing prices to fluctuate far more than they would if investors consistently took into account earnings across full economic and industry cycles.

This short-term bias creates opportunities for active portfolio management. By carefully selecting investments based on long-term cash flow potential rather than short-term earnings fluctuations, we aim not only for strong long-term returns but also for the comfort of knowing our investments are fundamentally sound—backed by real cash flows rather than speculative hopes that someone else will pay more later.

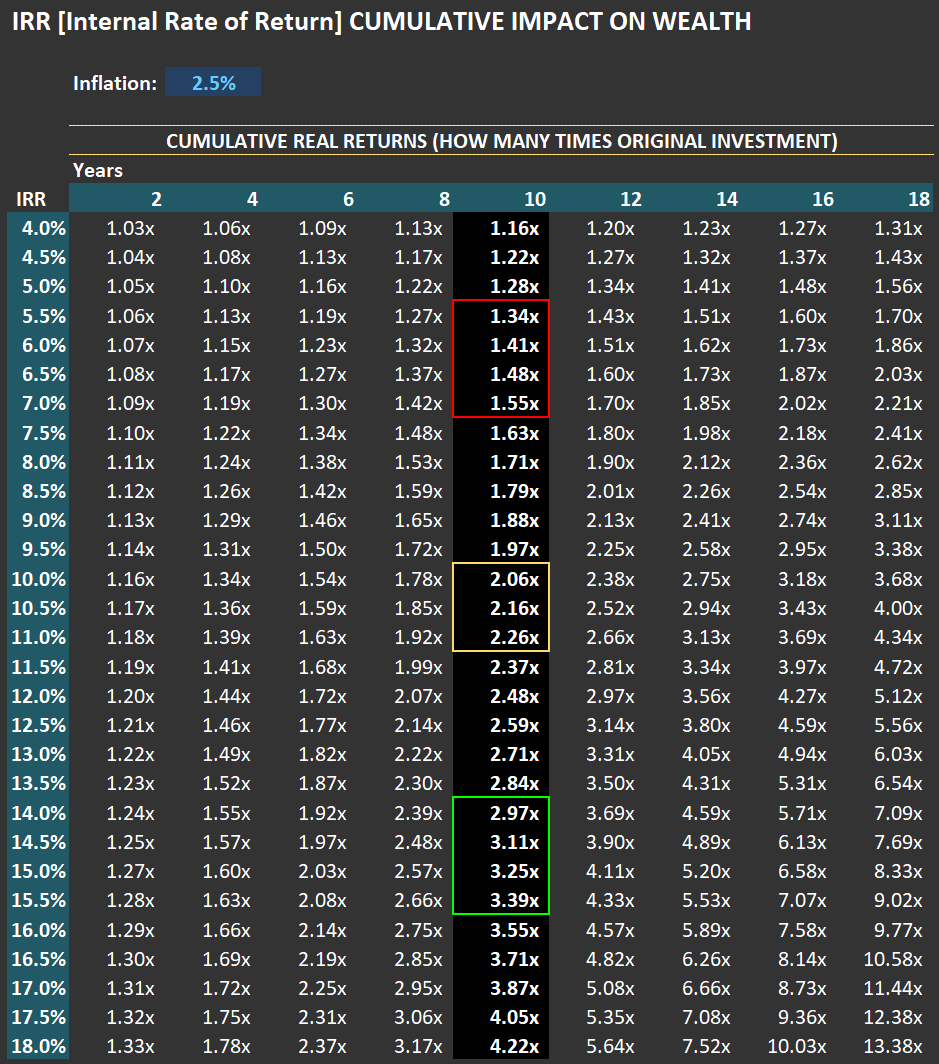

Every company entering RIM’s portfolio on the long side has an “above normal” expected IRR, while those on the short side have “below normal” expected IRRs. To illustrate what “normal” looks like within RIM’s Circle of Competence (CofC), see the table below. It shows cumulative real returns—how many times your initial investment would grow—after a given number of years based on the observed IRR at purchase.

I’ve selected the 10-year mark as a practical proxy for “long term.” For instance, if you bought something today with an implied IRR between 10% and 11%, after ten years, your investment would grow—in real terms—to between 2.06x and 2.26x your original investment (highlighted in yellow). This range represents the average observed returns over very long cycles (20+ years) for companies within RIM’s CofC.

The green box highlights the typical IRRs (14% to 15.5%) at which we initiate long positions. Conversely, the red box shows typical IRRs (5.5% to 7%) at which we initiate shorts. In practical terms, when RIM initiates a long position in a company, we expect cumulative dividends (and/or cash payment for the business) equivalent to roughly 3.2x our initial investment; shorts typically offer only about 1.4x—a significant 120% difference in expected returns.

Ultimately, regardless of personal hopes or beliefs, the Market collectively prices companies based on expected future cash flows available to shareholders. Therefore, successfully investing requires both skill and discipline: skill in accurately forecasting long-term earnings prospects and discipline in buying when earnings—and thus prices—are unusually low (and shorting when they’re unusually high). This disciplined approach is precisely what I practice every day at RIM.

(*) My insights are built upon 67 detailed valuation models I’ve meticulously developed and refined over the past two decades. Additionally, I rely heavily on Odysseus—RIM’s custom-built portfolio management, trading, and reporting tool—which I developed using Python and some of today’s fastest computational libraries.

Understanding Transportation Trends Through Cass Index Charts

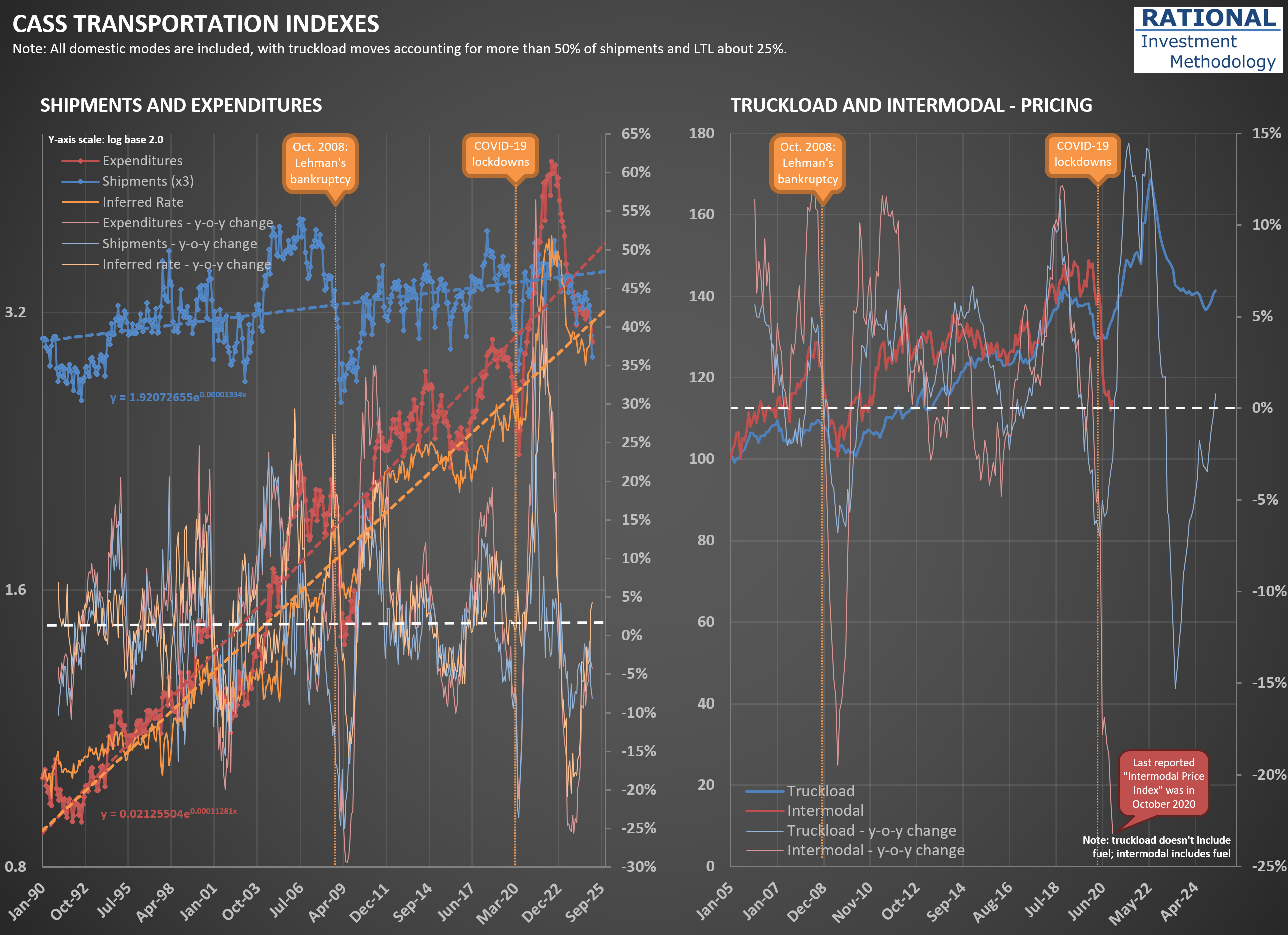

I’m writing a Portfolio Action [PA] to RIM’s clients and referencing the chart below. I’m posting it here so my clients can see a more complete explanation of the Cass Transportation Indexes and—if on a computer—zoom in on the chart itself. As always, here is a disclaimer: the charts I share with you are for my professional use. I share them “as is” because I want you to know what I do daily. Therefore, they are not “presentation ready” charts. They are busy, with a lot of lines. However, they serve their purpose well: quickly displaying information (lots of it) to me. So take the time to analyze the charts I’m sharing with you, so you can absorb all the information they portray.

Let’s go to the charts themselves. On the left, the most crucial series are the shipments (dark blue) and expenses (dark red). The series covers all modes of domestic transportation, but truckload shipments account for more than 50% of the index. LTL (Less Than Truckload) is close to 25%. So, this is mostly a trucking-related index.

Note that “expenses” in this context means how much the user of trucking services paid trucking companies for their services. In other words, expenses equal revenue to trucking companies. Also note that these two series are on a log scale base 2. Why a log scale? Because the series is so old, you would be unable to see variations in the distant past (as older values - especially for the expense series - are much smaller than newer ones).

I also added to the charts a reference to two important events: the month Lehman Brothers went bankrupt, significantly exacerbating the economic downturn in 2008, and the lockdowns in March 2020. Also note that both series have a dashed line crossing them—they are exponential trendlines (which in a log scale appear as a straight line). They help gauge where we are in a cycle.

For instance, observe how much expenses were over its trendline during the pandemic, while shipments - albeit above the trendline - had a much smaller peak. This is because shippers were willing to pay a lot to secure transportation capacity due to the abnormal consumption triggered by excessive government stimulus. Observe how the light-orange line - showing a year-over-year [y-o-y] delta in the inferred rates charged - had its most significant spike ever during the pandemic.

Last, the light-red and light-blue lines show y-o-y changes in the shipments and expenses series. Note how both have been in negative territory for a while. In January 2025, they completed 24 months of continuous decline, the most prolonged period since the series started in 1990. A few crises got close, but none reached the 2-year mark. That is why trucking company CEOs say we are in a “freight recession.”

The chart on the right shows a couple of series trying to isolate prices for (i) truckload and (ii) intermodal. They will show cycles similar to those in the series on the left. However, Cass claimed they had difficulty measuring intermodal prices during the pandemic and interrupted the series' release. I hope one day they return to reporting it.

The Cass Transportation Indexes are a fantastic source of insights on the transportation industry. To complement it, I also like to see what the American Trucking Association [ATA] data tells us. You should check the post I made a few days ago using the ATA data (here).

Fundamental Analysis Spotlight: $OI and Market Mispricing

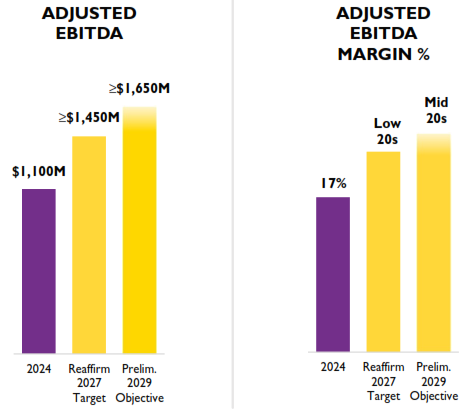

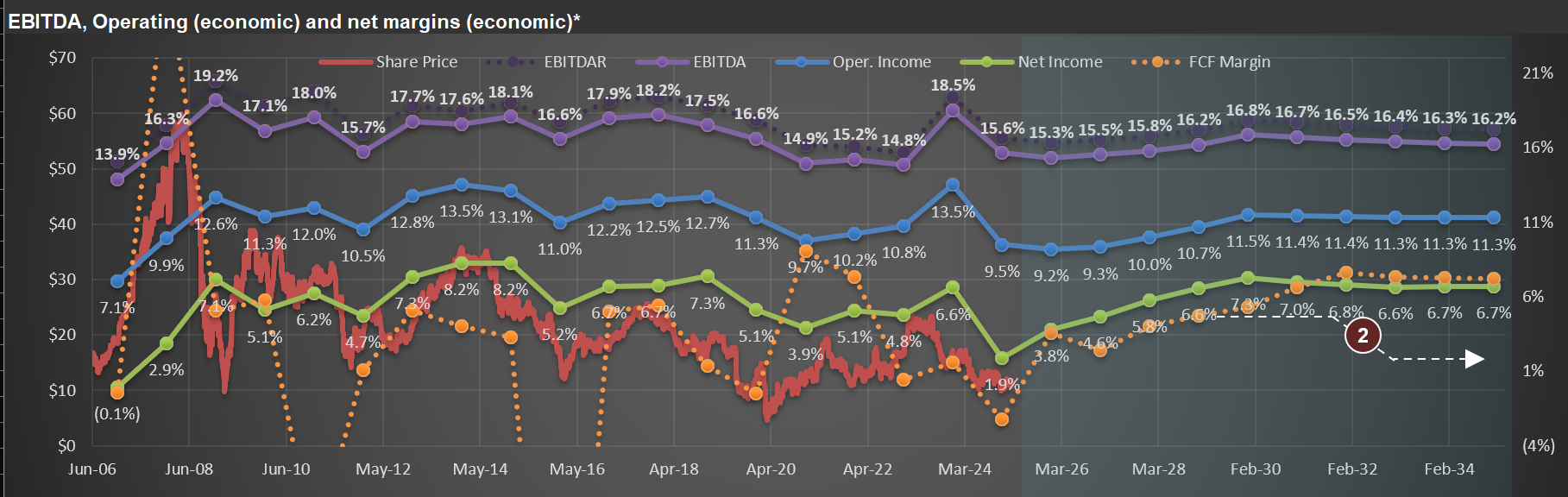

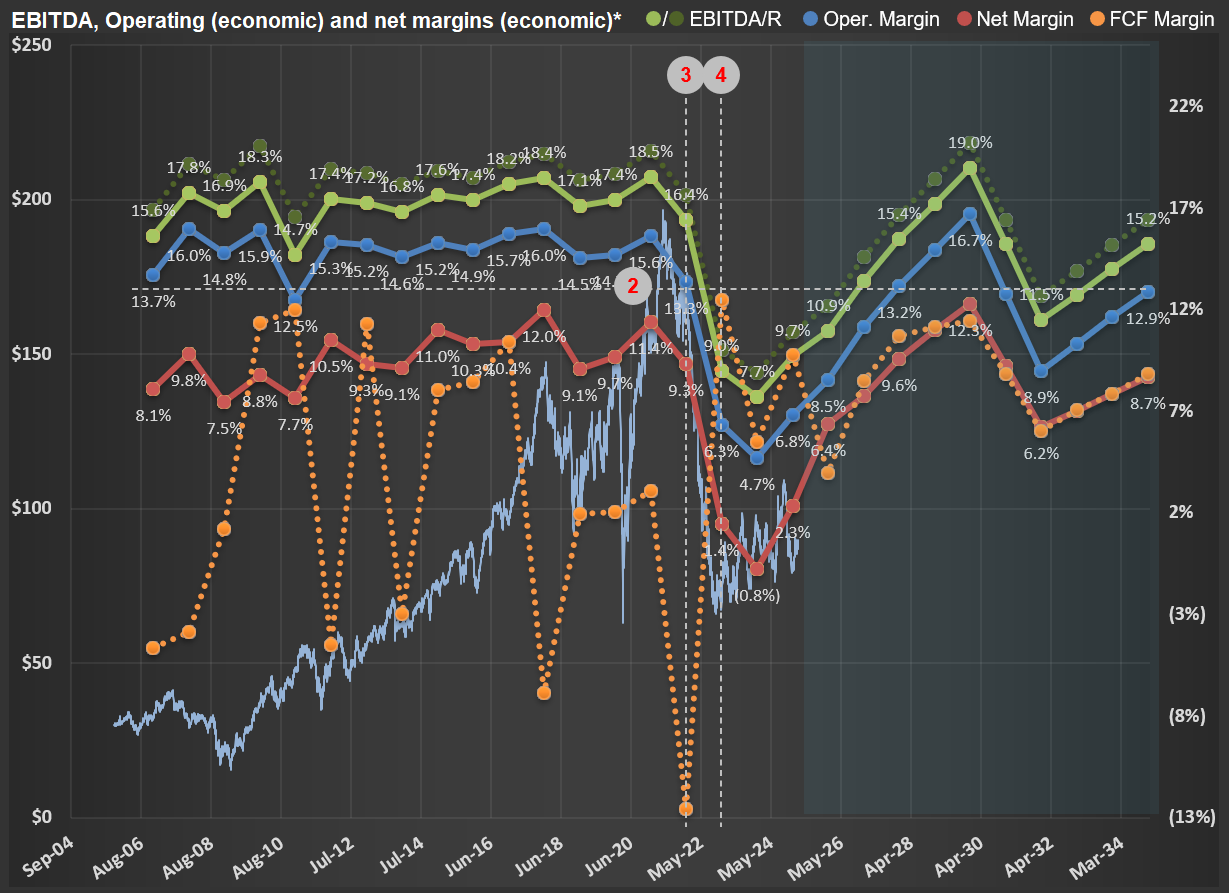

I attended the $OI (OI-Glass) investor day event and wanted to share some interesting insights. Look at the first chart below, which I pulled from their extensive 91-page presentation. Notice the projections for 2029: management targets EBITDA margins in the “mid 20s,” so let’s call it “around 25%.”

Now, check out the second image—this one shows my base-case scenario for OI-Glass. By 2029, my estimated EBITDA margin stands at 16.8%. I’m slightly more conservative in calculating EBITDA than management, as I leave some expenses on my calculations that they might exclude. So let’s round up my estimate to 17%.

But here’s the impressive part: OI-Glass appears substantially undervalued even using my conservative margin of 17% (or 8 percentage points below management’s target). Historically, the market has valued companies similar to OI-Glass—assuming my base-case scenario—at around 4 to 5 times today’s valuation. It would be much more with EBITDA margins of 25%!

This is a perfect illustration of market inefficiencies. The market isn’t fully pricing future profitability improvements implied by OI-Glass management’s expectations. Instead, share prices often reflect current EPS disproportionately. This is precisely where fundamental analysis adds value. If you’re skilled at (and have the time to dedicate to) understanding businesses and accurately forecasting long-term earnings potential, you’ll be well-positioned to identify opportunities (long or short) that eventually get recognized by the Market’s mechanical pricing heuristics.

Hence, I focus on first understanding what companies do and in which context (e.g., their competitive environment). Only after that do I spend time modeling a company in excruciating detail (also a necessary step to quantify your understanding of the business). With such an approach, I hope to be an “investor” and not a “speculator " (who blindly hopes that share prices move in their favor).

Is CSX's Growth Engine Losing Steam?

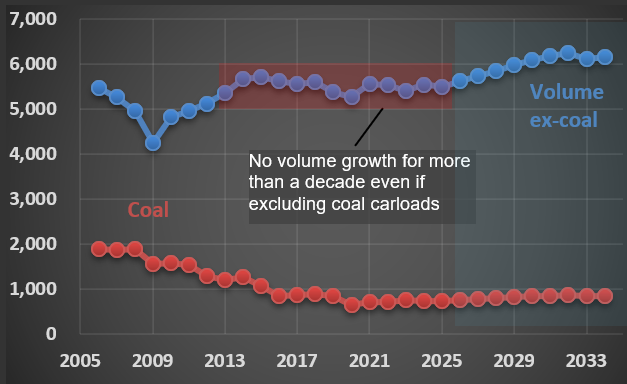

I’m currently analyzing $CSX (CSX Corporation), one of the leading railroad operators in the US. Look at the chart below: the red line represents coal carloads, which have significantly declined over the past two decades as the country transitions away from coal as an energy source.

The blue line shows carloads for all other industries CSX serves—think chemicals, materials, minerals, forest products, automotive (from parts to finished vehicles), and intermodal containers (those versatile boxes that seamlessly move between trucks, trains, and ships). Interestingly, volumes for these categories have remained relatively flat over the last 13 years.

Yet, despite stagnant volumes, CSX’s earnings per share—and consequently its share price—have risen considerably during this period. This growth has primarily been driven by aggressive cost-cutting measures and consistent price increases, enabled by the duopoly structure common among railroads. However, recent slow declines in margins could suggest that this favorable dynamic is beginning to shift.

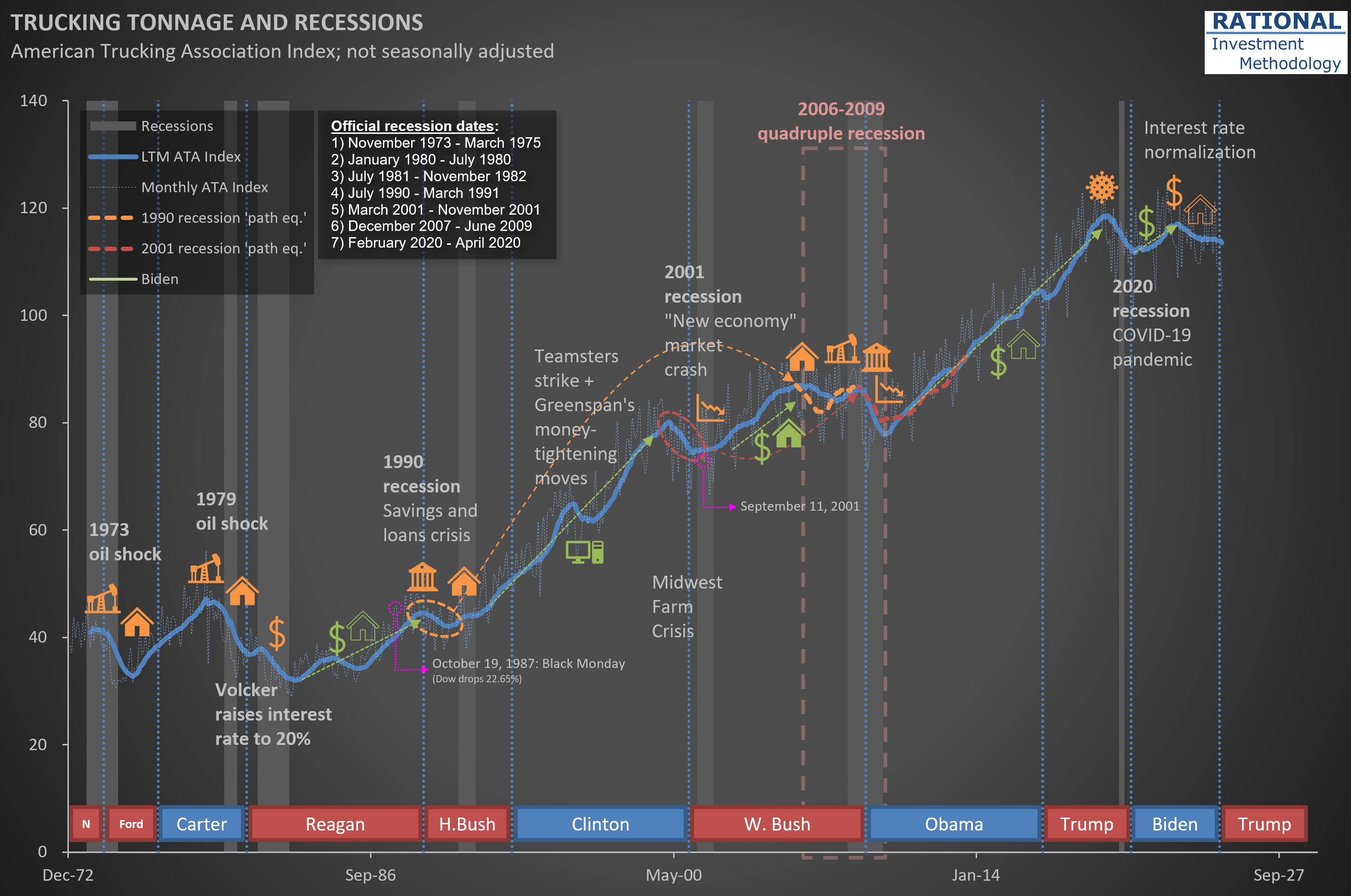

What Trucking Tonnage Tells Us About Market Crashes and Recessions

I was recently asked if a market crash can trigger a recession. In short: yes, it certainly can—and it did in the early 2000s.

The chart below should look familiar to RIM’s clients. It shows trucking tonnage data from the ATA (American Trucking Association). The thin-dotted blue line represents monthly figures, which tend to be volatile due to weather seasons and holidays. I’ve added a thick blue line showing the Last Twelve Months (LTM) moving average to better identify trends.

Every turn in this LTM line has a story behind it—economies typically grow until something disrupts them. That’s why you’ll see annotations on the chart marking significant events: sharp oil price spikes, declines in housing starts, rising interest rates, banking crises, market crashes, and even a global pandemic (I never imagined I’d be adding that one!).

Take a closer look at the early 2000s. Trucking tonnage began declining around March 2000—exactly 25 years ago—coinciding with the internet bubble bursting. While the tragic events of September 11th certainly disrupted economic activity further, the downturn had already begun well before then. However, the market crash was clearly the initial trigger.

Could we be experiencing something similar today? Nobody knows, but there’s no point obsessing over it. Unless, of course, you invest in companies for which it is challenging—if not impossible—to predict long-term sales and profitability. These types of companies are the core protagonists—in terms of how much they decline—during bubble bursting years.

As equity investors, our focus should remain on thoroughly understanding a select group of companies and accurately modeling their financials based on company- and industry-specific data. Then, when the market inevitably overreacts to short-term news or temporary EPS fluctuations, we’re ready to act decisively. If you’ve been following RIM’s approach, you know that’s exactly what I do every single day.

What Harley-Davidson's Financing Data Reveals About the US Consumer

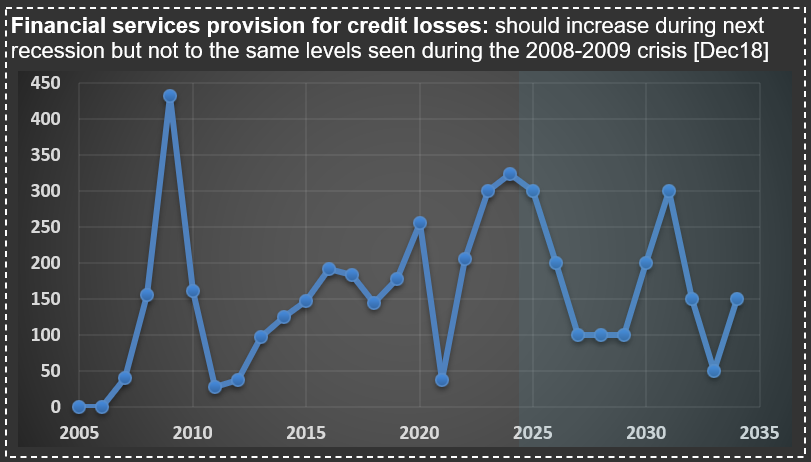

$HOG (Harley-Davidson) operates as two distinct businesses: a motorcycle manufacturer and a consumer financing provider. In fact, Harley-Davidson Financial Services financed over 70% of the motorcycles sold in 2024. Like any company offering financing, it must set aside provisions for potential credit losses.

The chart below illustrates these credit loss provisions (in basis points) relative to their total outstanding receivables portfolio. Notice the significant spike in 2009 during the Great Financial Crisis (GFC)—a severity that’s tough to surpass. (You might also spot my 2018 comment, noting future cycles would come, though likely not as extreme as the GFC.)

But more importantly, observe how elevated these provisions have been over the past two years (and likely continuing into 2025). Those surprised by recessionary signals today simply haven’t been paying attention to the right indicators. As I’ve mentioned in previous posts, the US consumer has already exhibited recessionary behavior for some time.

Are Investors Overpaying for Growth? O'Reilly's SSS Under the Microscope

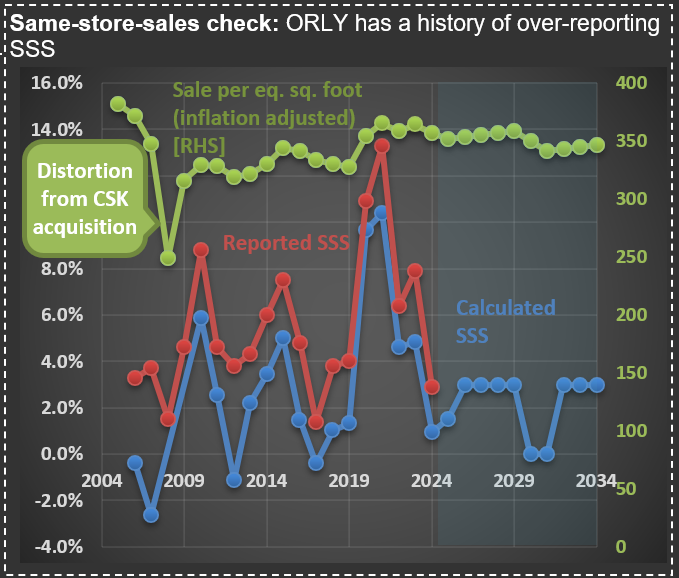

When analyzing retailers' sales, it is necessary to adjust “same-store sales” (SSS) by the age of the square footage. This adjustment is required because newer stores typically generate lower sales per square foot than established locations, as it takes time for customers to discover and frequent newly opened convenient locations.

Without these adjustments, there’s a significant risk of overestimating actual sales growth. In my analysis of $ORLY (O’Reilly Automotive), I’ve consistently calculated lower growth figures than what they’ve reported for several years now. As you can see in the picture below, ORLY’s reported figures (red line) consistently outpace the properly adjusted metrics (blue line).

Over the past two decades, ORLY has reported impressive average SSS growth of 5.6% annually. However, my calculations suggest they’ve overestimated this growth by approximately 2.9% per year. This means their true SSS growth rate is closer to 2.7%—essentially tracking with inflation.

This discrepancy may have contributed to ORLY’s current valuation, which stands at more than 30x earnings. At today’s price, an investor is accepting a potential return of only about 5.5% annually (from a business owner’s perspective, similar to how Warren Buffett would evaluate a complete acquisition). Is such a modest return sufficient for your investment goals?

Less cars but higher sales in real terms? Inflation confusion at play

After finishing my $AAP (Advance Auto Parts) work, I’m updating my analysis on $ORLY (O’Reilly Automotive). The difference in performance between these two stocks is staggering, but—given current price levels—you might be surprised which offers materially better prospects for higher IRRs (Internal Rate of Return) for the long-term holder.

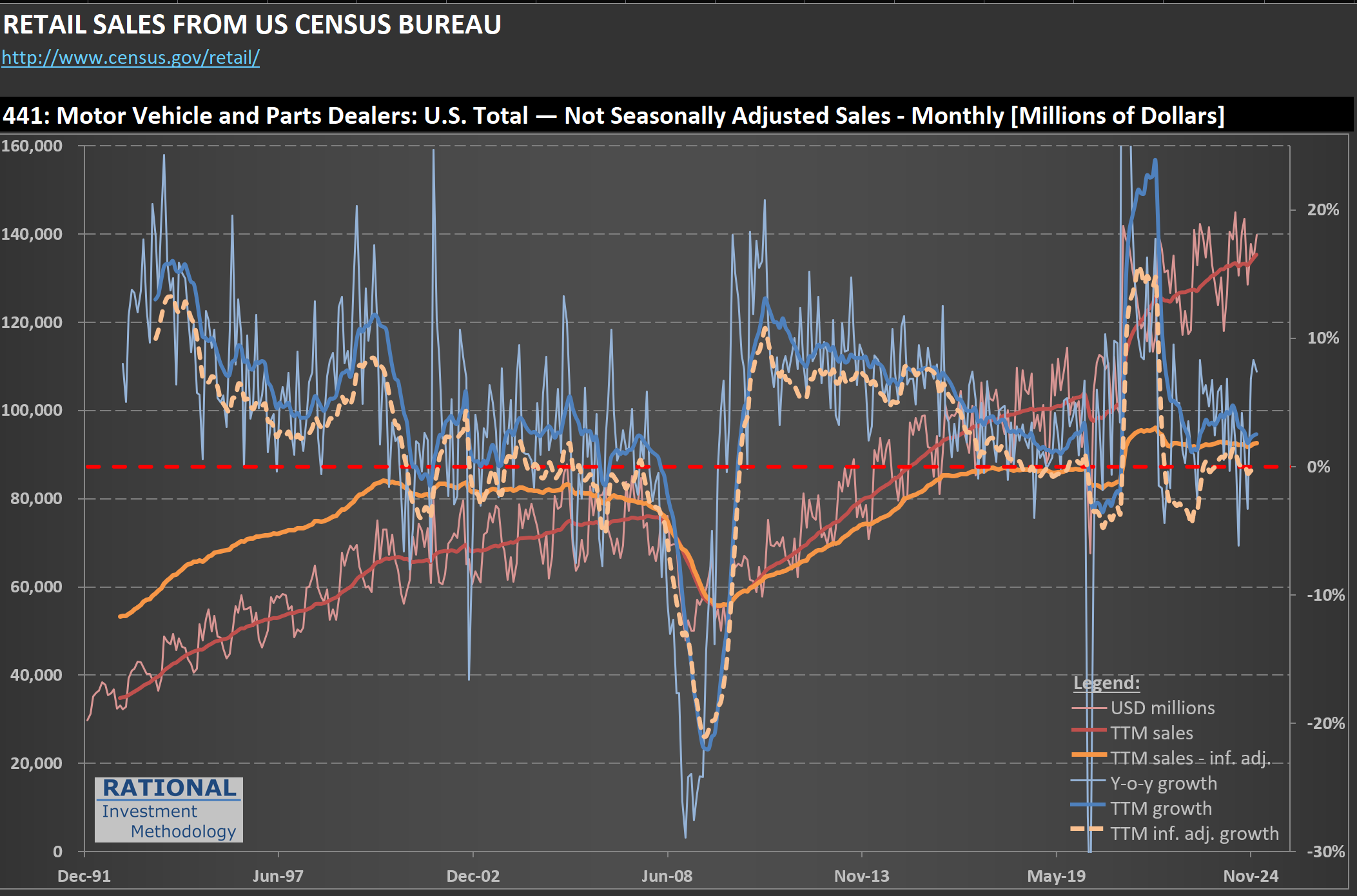

The chart I’m sharing below offers a high-level view of motor vehicle (and parts—a small part of these figures) sales. The line to focus on is the orange one: it shows sales adjusted for inflation. Now if you look at the last post (here) showing the number of vehicle sales, you will see a discrepancy. I.e., the number of vehicle sales is lower (by -7,5%) while the total dollars spent is higher (by +6.4%) compared to pre-pandemic levels.

A change in mix (more expensive cars, less cheap cars) could explain part of the delta. But another factor is at play: the overall inflation ratio (which I use to normalize sales) doesn’t capture the actual inflation in car prices. These more expensive (in real terms) cars lead to lower unit sales than before. It doesn’t help that the American consumer is also in a recession - I discussed it on a post yesterday (here).

Understanding long-term drivers for auto parts sales

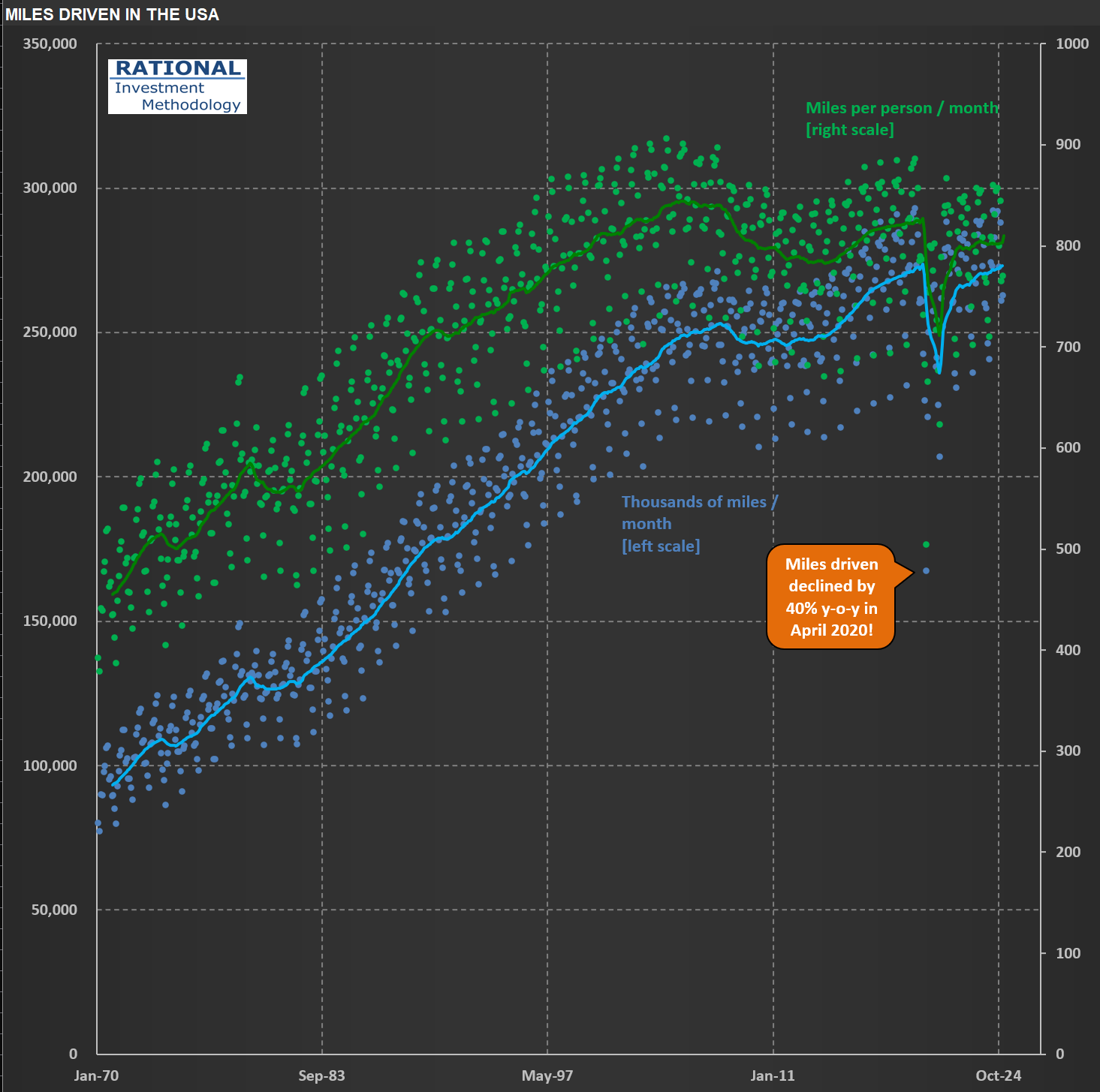

I’m working on $AAP (Advance Auto Parts) today, one of the top three auto parts retailers - more on the business later. Now I’m sharing two charts I have in my analysis to ensure I’m aware of some secular trends affecting the industry.

The first shows total miles driven (in blue) and miles driven per person (in green). The lines are a trailing 12-month figure. Total miles driven still grows, but not by much. It is interesting to note, however, that miles driven per person peaked in 2005—two decades ago!

If people drive less, they should be buying fewer cars—at least per capita, right? We observe this in the data—see the second chart. The blue dots show cars sold per month. In red, an index of how many cars were bought per capita is shown. The peak of car purchases in the US happened in the summer of 1979! The last peak of absolute numbers of vehicles sold in 12 months happened 25 years ago, in the summer of 2000.

These figures help me calibrate the underlying potential auto parts sales. On top of the drivers I just shared, I still need to consider how long cars last nowadays. For example, if one observes that we have an “aging fleet” in the US and concludes that they are going to need more auto parts, that might not be the case if cars just last longer. Technology has made parts more durable. Hence you have to consider a cascade of effects when trying to understand what will impact sales in the long run.

Valuation Distributions: Why 'Is the Market Cheap?' is the wrong question and how to use it to spot recessions

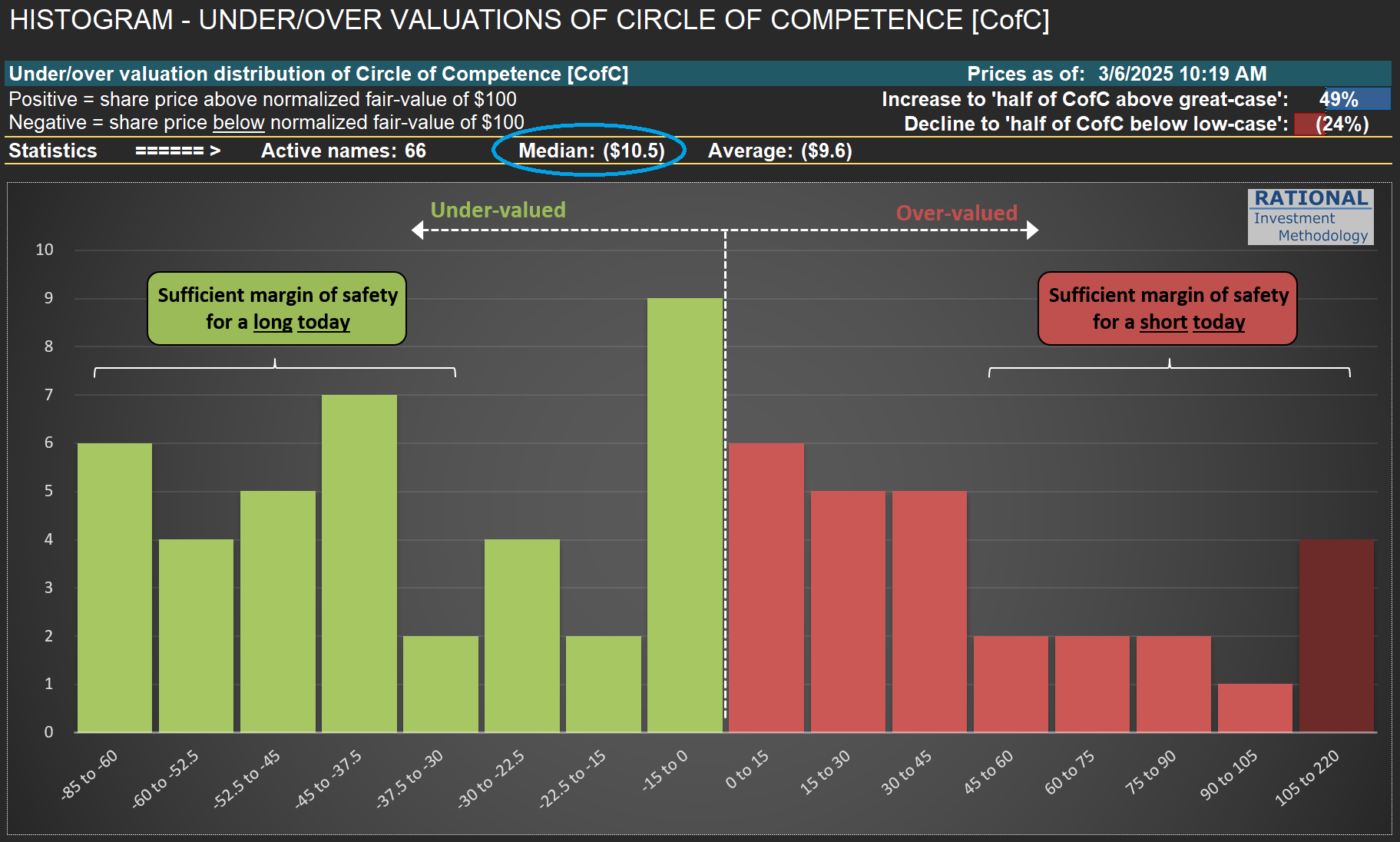

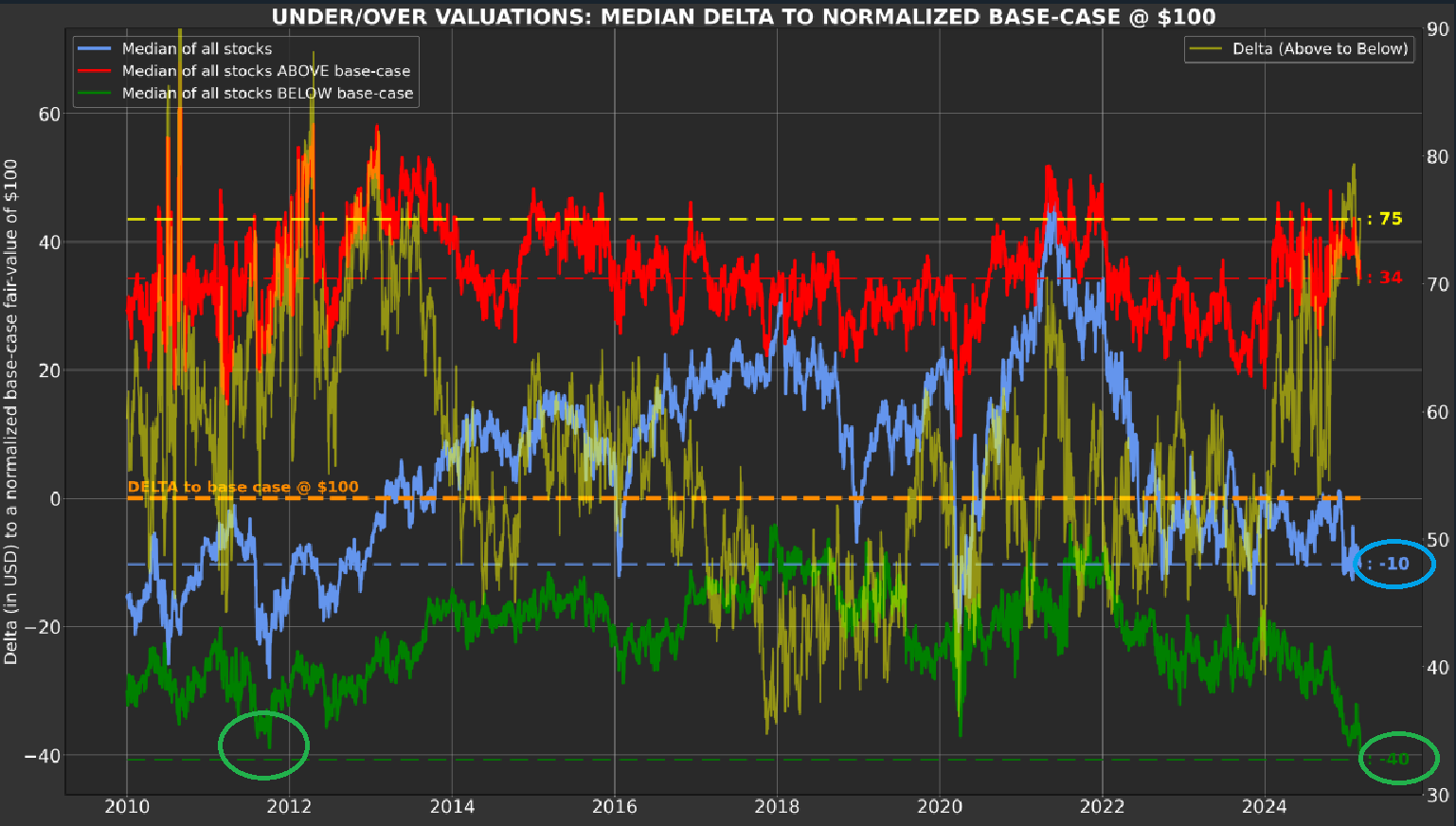

Frequently I’m asked if I think “The Market” is expensive or cheap. I know the person asking the question wants a yes/no answer. Still, I must explain that - although you could provide a single number - it would be a very incomplete as any market is a distribution of under/over valuations of all the companies in that market. So if you want to know if the S&P500 is cheap/expensive, you have to have an assessment of the under/over valuation of 500 companies!

What I do day in and day out at RIM is to update and polish reference fair values for all the companies on my CofC (Circle of Competence). By normalizing these fair values to $100/share, I can build the histogram in the first picture below. So for “RIM’s market”, the average company is undervalued by ~10% (see figure circled in blue on the chart). But this is an average. Reality is much more complex - some companies are cheap while others are expensive. Hence, it is crucial to see the data in a histogram.

But we can do better (as long as you have a sophisticated tool like Odysseus - RIM’s portfolio construction, trading and reporting tool). Take a moment to review the second chart below. It shows the averages, over time, of all companies (in blue), the expensive ones (in red—they are also in red in the histogram), and the cheap ones (in green—they correspond to the ones also in green in the histogram).

I want to bring to your attention the green line—cheap companies are now undervalued by 40%! See the -40 figure circled on the right side of the chart. This is more extreme than what was observed in the summer of 2011 (period circled in green). Can it get worse (i.e., more undervalued)? Of course - the second chart starts in 2010 because I want to exclude 2009, as undervaluation at that period was almost surreal. But understand this - the US is in a full-blown recession for some industries. Look at the post I did for $BC (Brunswick) here and $HOG (Harley Davidson) here. Sales figures at these industries (per capita) are at 2009 levels. The same is true for anything discretionary, from mattresses to toasters.

So, are we in a recession? I won’t debate potential distortions to broad GDP figures—that define whether the country is in a recession or not—with its multiple adjustments, as macro-economics is not my specialty. However, the American consumer is definitely in a recessionary mood. That is why we have so many cheap stocks (and by an uncommon amount) - they are primarily in the consumer/housing segments.

Last, you can see that the red line on the second chart is still relatively high. That is because some industrial names, which have a delayed cycle compared to consumers, are only now showing a substantial correction in sales and margins. However, valuations in the sector will eventually reflect the harsh reality for some companies in this group.

So what should one do out of this long blog? I hope it will help by reminding you to discuss more precisely what it means to say “the market is expensive” (or cheap). I want you to think about distributions. Moreover, also to think about the possibility of someone really having an assessment for all the companies that are part of whatever market they are referring to. So next time someone tells you “I think the S&P500 will go up” (implying they think it is cheap), you can tongue-in-cheek say “Wow, I didn’t know you had 500 valuations!” Otherwise, any opinion is nothing more than a blind guess.

Farm Cash Flow: The Hidden Driver of Agricultural Equipment Sales

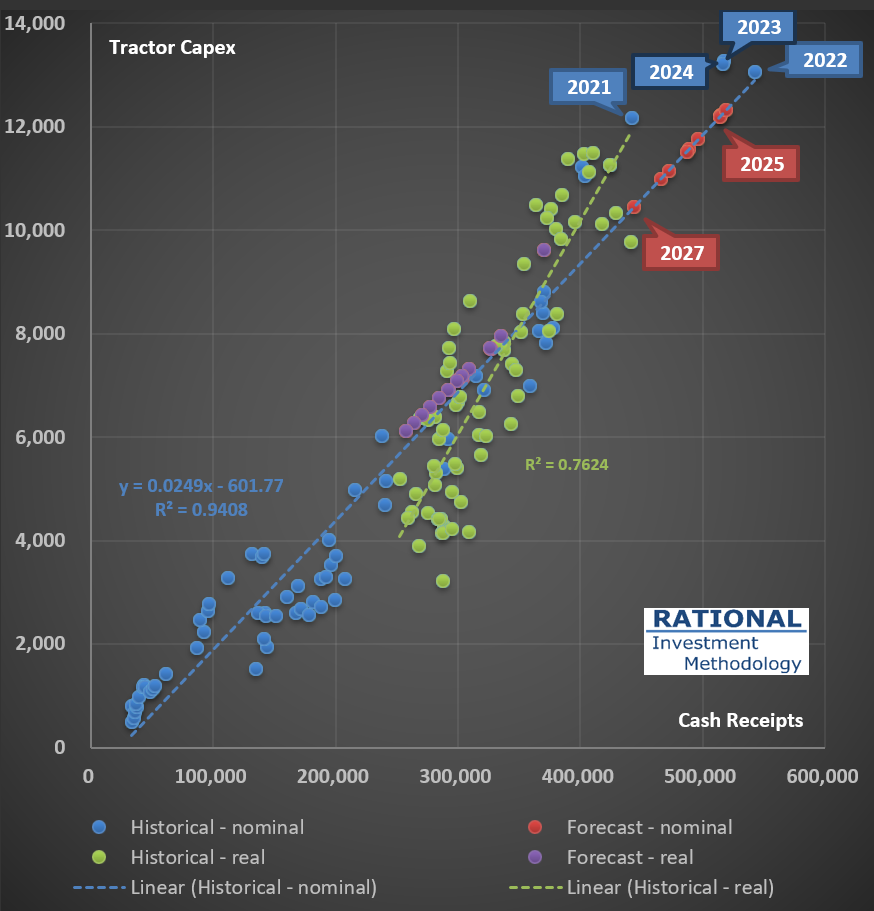

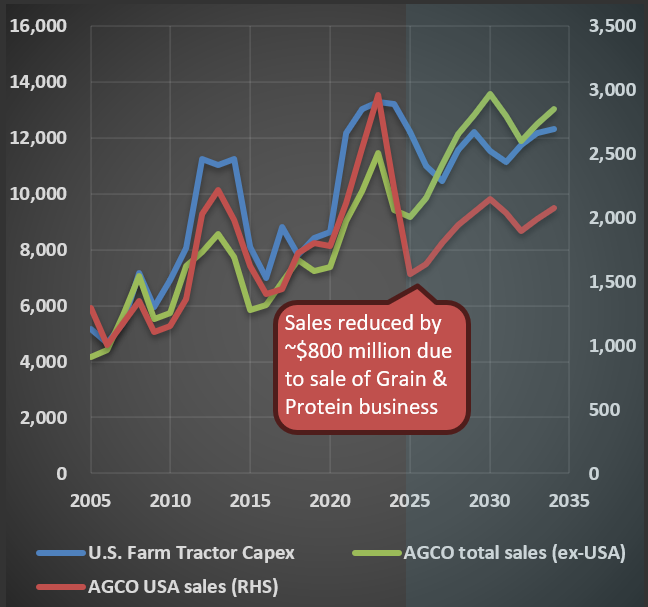

As I delve into my $AGCO [AGCO Corporation] analysis today, I’m reminded of the fascinating relationship between farm economics and agricultural equipment sales. The agricultural sector’s financial health, particularly U.S. farm cash receipts (or net cash income), has historically been a key indicator of agricultural capital expenditures.

Take a moment to examine the first chart below. It beautifully illustrates the strong correlation between tractor sales and cash receipts, highlighting the direct impact of farm profitability on equipment purchases.

Even more intriguing is how we can use U.S. farm cash receipts as a proxy for global trends. Despite AGCO and other agricultural equipment companies operating on a global scale, the interconnected nature of agricultural commodity markets allows for this simplification. The second chart demonstrates this phenomenon, showing remarkably similar sales dynamics between U.S. and non-U.S. regions.

In my forecasting work, which includes $DE [Deere & Co.], I’ve found the USDA’s projections of U.S. farm cash receipts to be invaluable for predicting long-term revenue trends in the agricultural equipment sector. This approach has consistently yielded accurate results, providing a solid foundation for investment decisions.

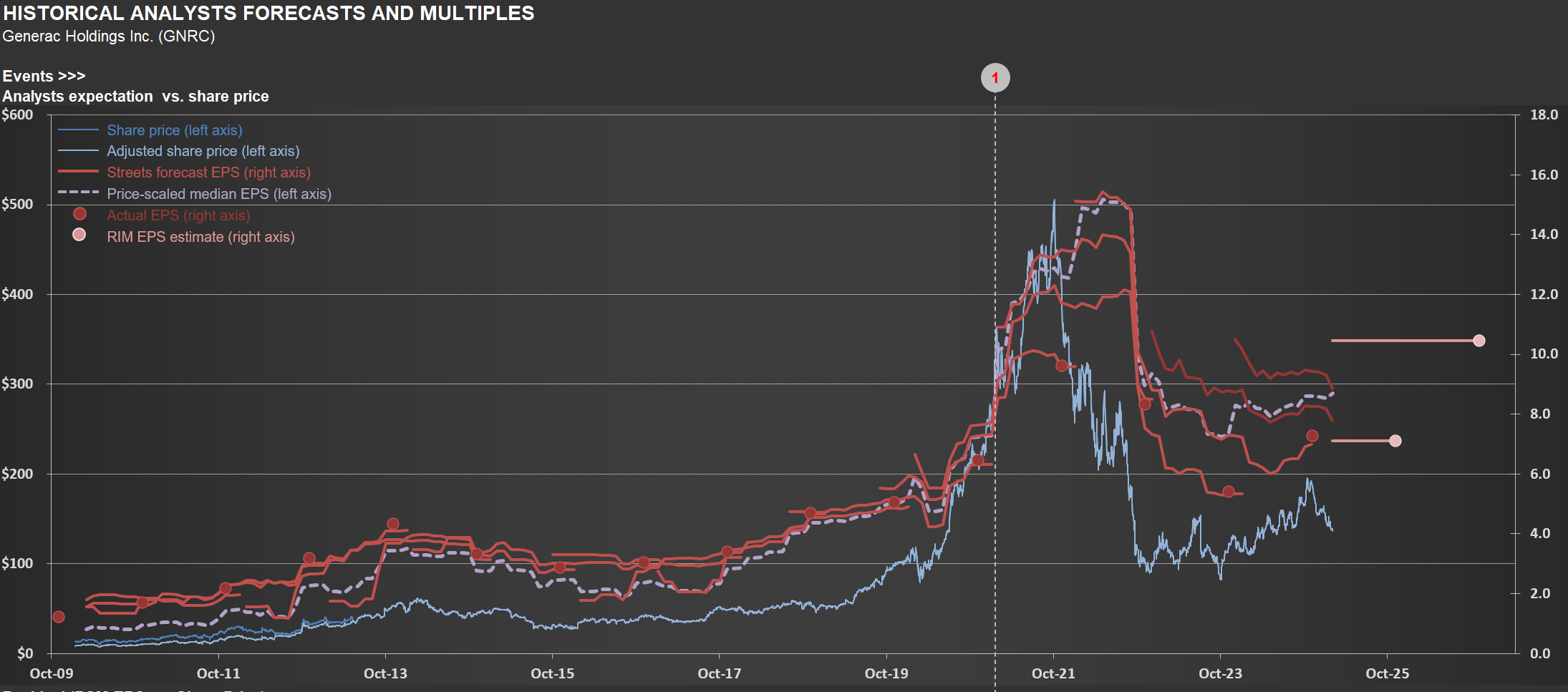

Market Prices vs. Fair Value: Why Today’s Quote Isn’t the Full Story

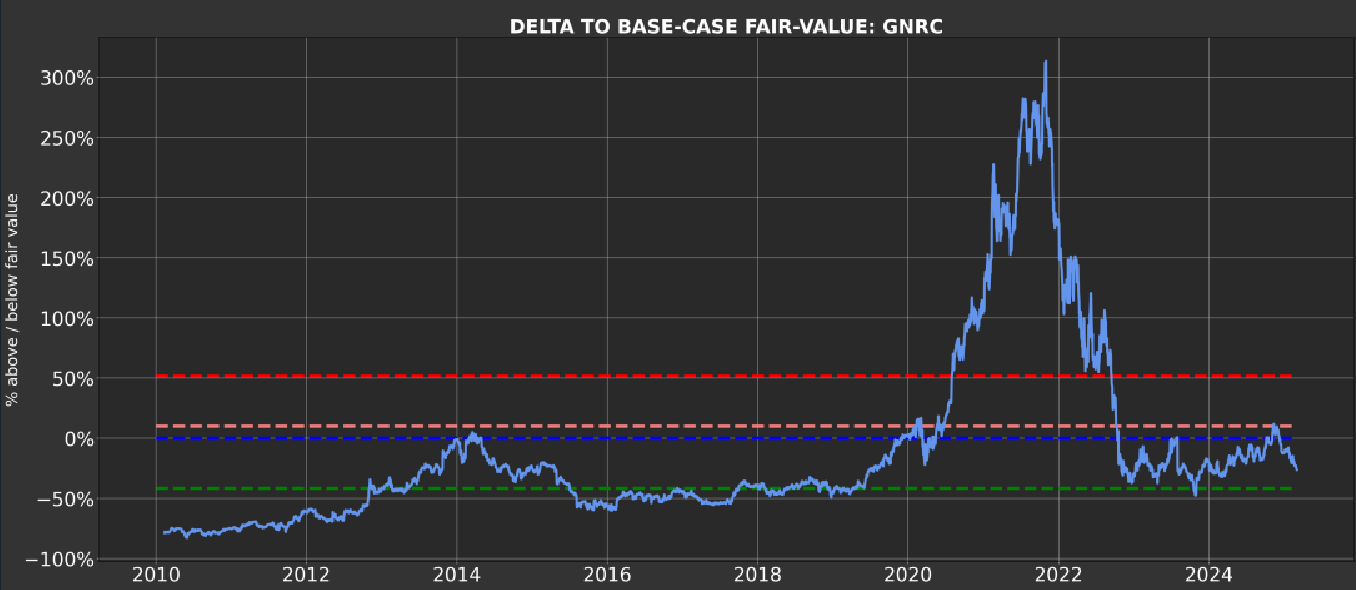

When assessing a company’s long-term value, certain metrics can be misleading—and today’s share price often tops the list. Take $GNRC [Generac] as an example. Since its IPO, short-term earnings estimates (red lines in the first chart below) have closely tracked its share price (blue line). While markets are “correct” on average over time, valuations at any given moment frequently stray far from rational estimates of fair value.

The second chart, from Odysseus (RIM’s portfolio management tool), highlights this disconnect. The blue line shows the market price deviation from RIM’s fair value calculation. At $500/share in late 2021, Generac traded at a staggering 300% premium to its intrinsic value—a vivid reminder that asking “what is the market telling me?” can lead to flawed conclusions.

Key Takeaways:

- Extreme price deviations are common, driven by short-term sentiment rather than long-term fundamentals.

- Systematic strategies thrive on these dislocations, using disciplined triggers to enter long/short positions.

- RIM’s approach focuses on exploiting these gaps rationally, avoiding emotional reactions to market noise.

By anchoring decisions to intrinsic value—not fleeting price swings—investors can turn volatility into opportunity.

Recreational Boating Market Hits Recession-Era Levels

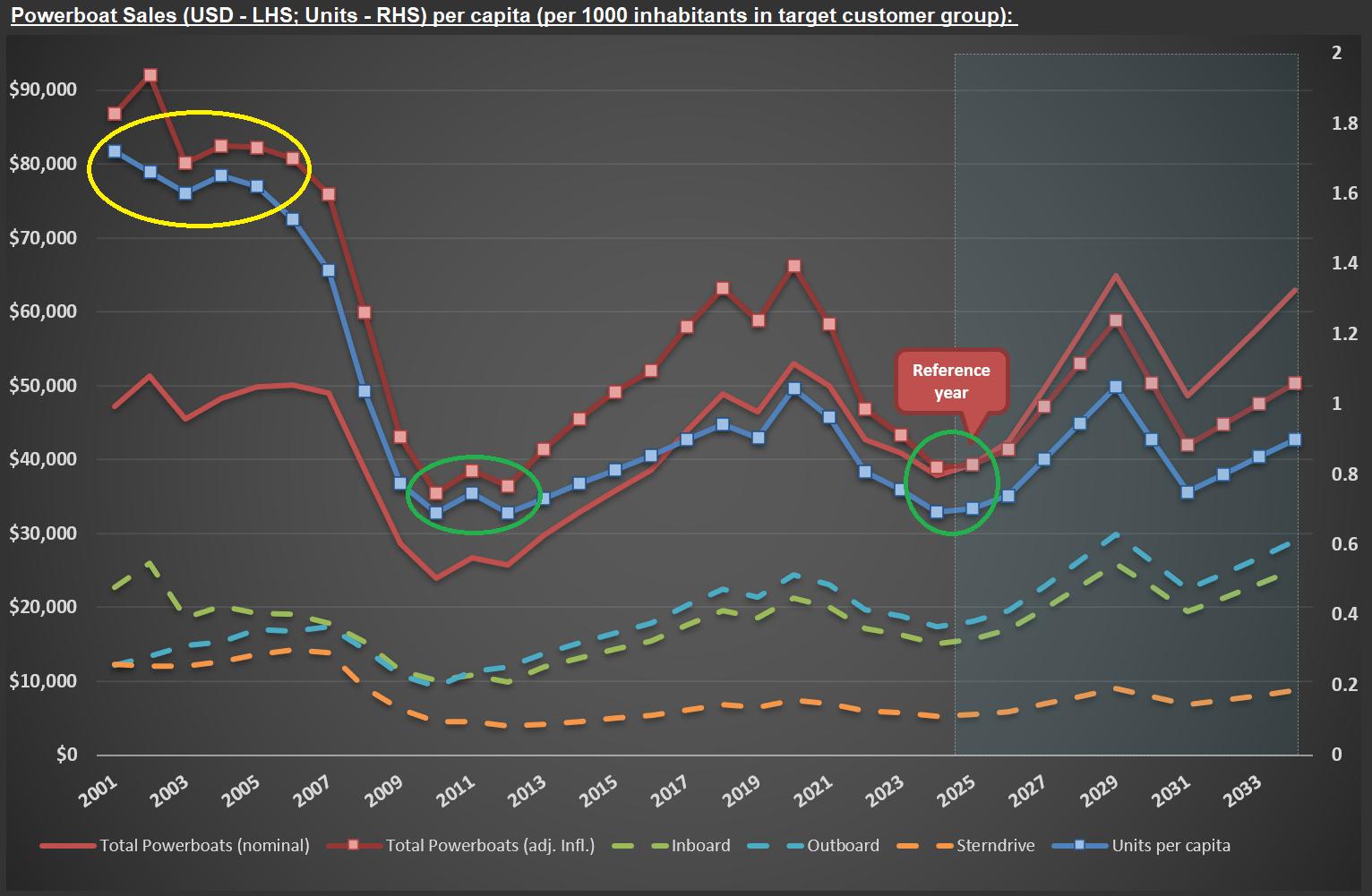

The recreational boating market reveals some concerning trends (which might lead to buying opportunities in the sector). The chart below shows powerboat sales estimates from my $BC (Brunswick) analysis, with the square-marked lines telling an important story. Sales volumes for 2024/2025, measured in units or inflation-adjusted dollars, have retreated to levels we haven’t seen since 2010-2012 – the early recovery period following the Great Recession (circled in green). Even more striking is how these figures compare to the pre-housing bubble era that ended in late 2005 (circled in yellow).

While headline GDP numbers might suggest economic health (I’ll share updated GDP charts and some comments in a future post), the recreational boating industry is experiencing significant challenges. This disconnect between broad economic indicators and sector-specific realities is worth noting for investors.

Brunswick’s recent actions highlight these difficulties. During their Q4 2024 conference call, the CEO candidly shared: “If you look from 1 January 2024 to 31 December, we unfortunately had to exit about 20% of our hourly staff and 7% of our salaried staff. The majority of that happened in the back half of the year when it was clear that we had to reduce our production levels to support year-end inventory levels that we needed to go into 2025.”

What does this mean for the broader discretionary spending landscape? I believe the American consumer is currently in a recession, as comments like the one above - and figures shown in the picture below - don’t show up during a healthy economy. But as always, this too shall pass, and Brunswick and other companies in the sector will revert to normalized sales levels.

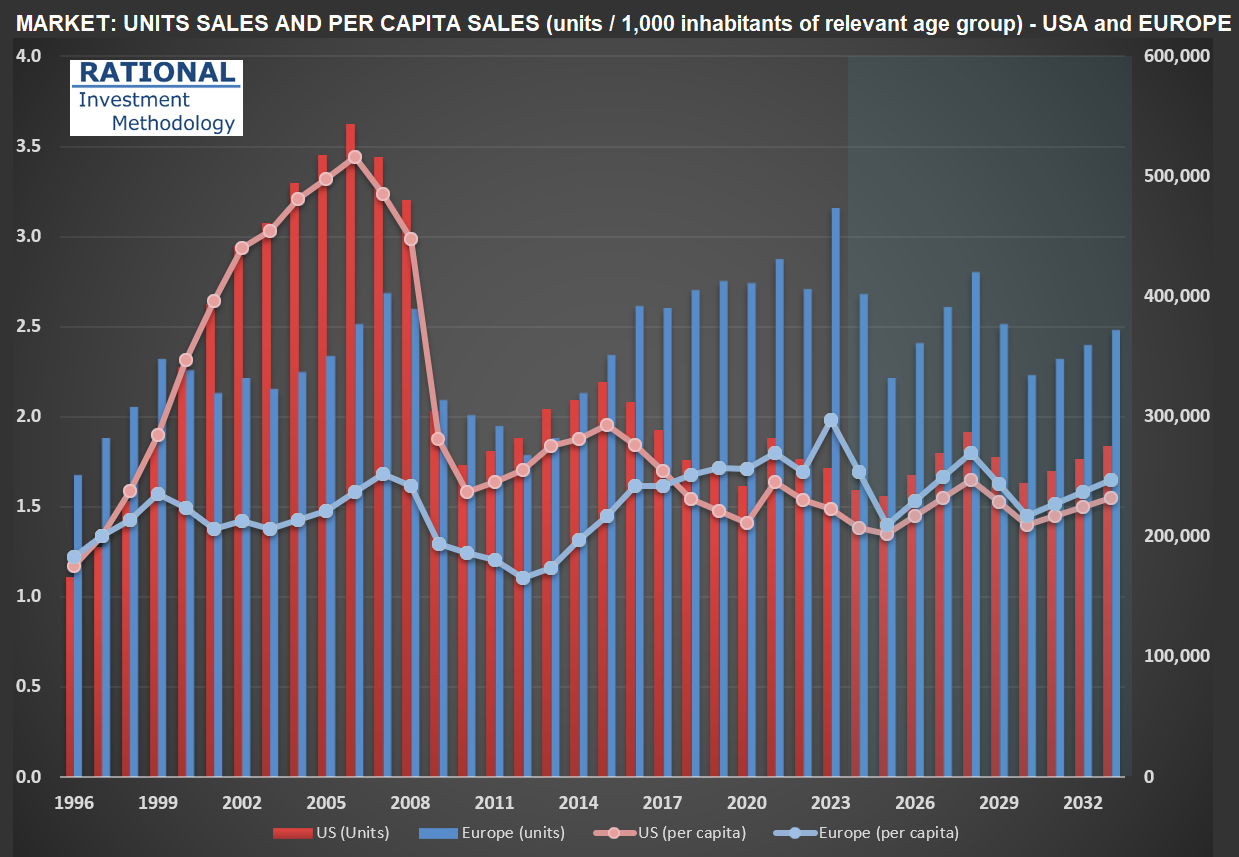

America's Declining Motorcycle Market and What It Means for Harley Davidson

Bloomberg is conducting a comprehensive series of special segments on $HOG [Harley Davidson], highlighting significant shifts in the American motorcycle market - hence this post. The evolution of motorcycle sales per capita in the United States has shown a staggering decline over recent years, as illustrated in the chart below.

Surprisingly, Americans now purchase fewer large motorcycles (over 600cc) than Europeans, despite having advantages that traditionally supported motorcycle ownership: abundant open spaces for riding, widespread garage availability for storage, and higher income per capita. This represents a fundamental shift in the American motorcycle culture that Harley Davidson has long dominated.

As part of my ongoing analysis of recreational vehicle markets, I’m currently researching $BC [Brunswick Corporation], a leader in the marine industry. I’ll be sharing insights on the boating sector soon, examining whether similar consumption pattern changes are occurring across different recreational vehicle categories.

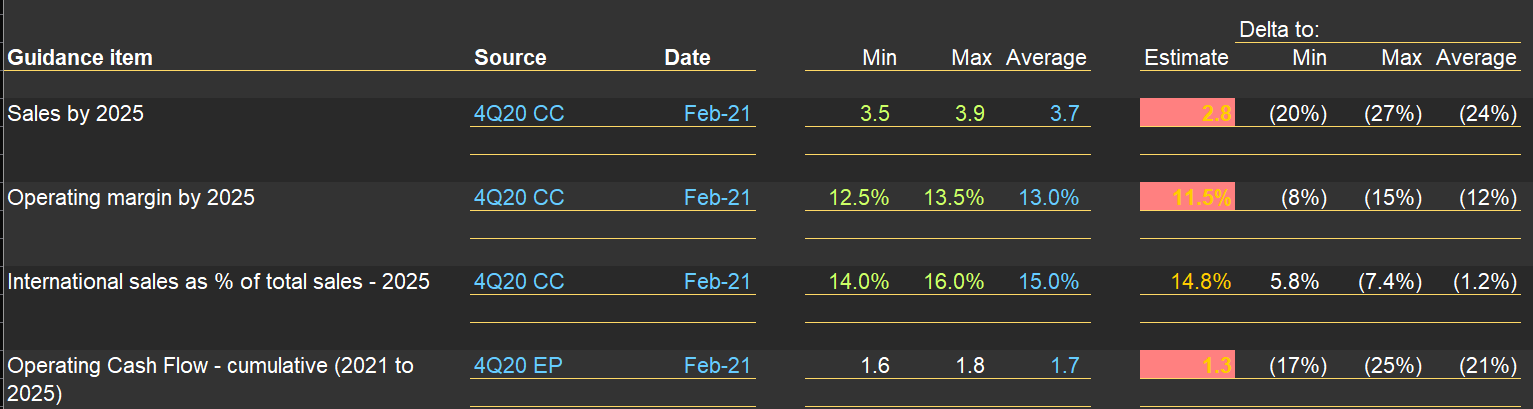

Carter's 2025 Forecast vs. Reality: A Humbling Lesson in Long-Term Guidance

Companies usually provide “guidance” for short term expectations. It helps when there are more complex changes in the P&L (for instance, after an acquisition and/or disposal). But sometimes, they provide longer-term guidance, as did $CRI (Carter’s) management in early 2021. The picture below shows their guidance for 2025 (on the left). On the right, what might happen (as we are now entering the “target year”). The delta between expectations vs. reality is significant (and I’m using a “normalized margin” for 2025 - the actual is expected to be closer to 7%). This example underscores how difficult it is to make forecasts. If it is that hard for a company’s management team that sells baby clothes, founded 160 years ago, can you imagine your chances to forecast sales and profitability in the technology field correctly? If you want to invest (instead of speculate), focus on mundane businesses. And even so you will be humbled by your mistakes!

US Census Bureau Revisions Shrink America's Youngest Population: Implications for Carter's Future Market

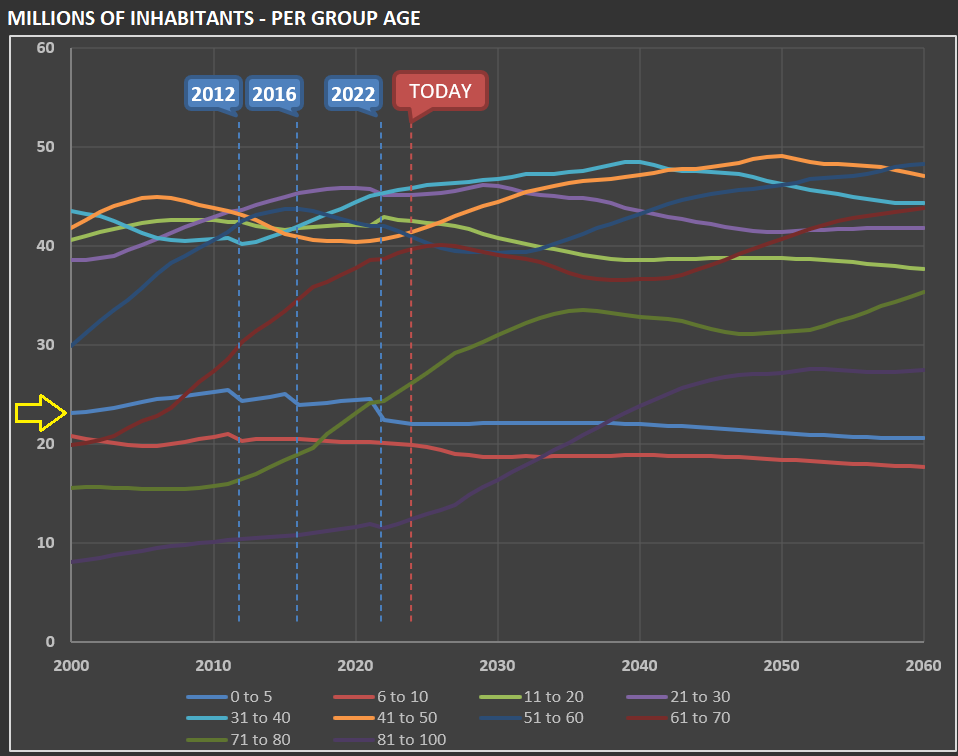

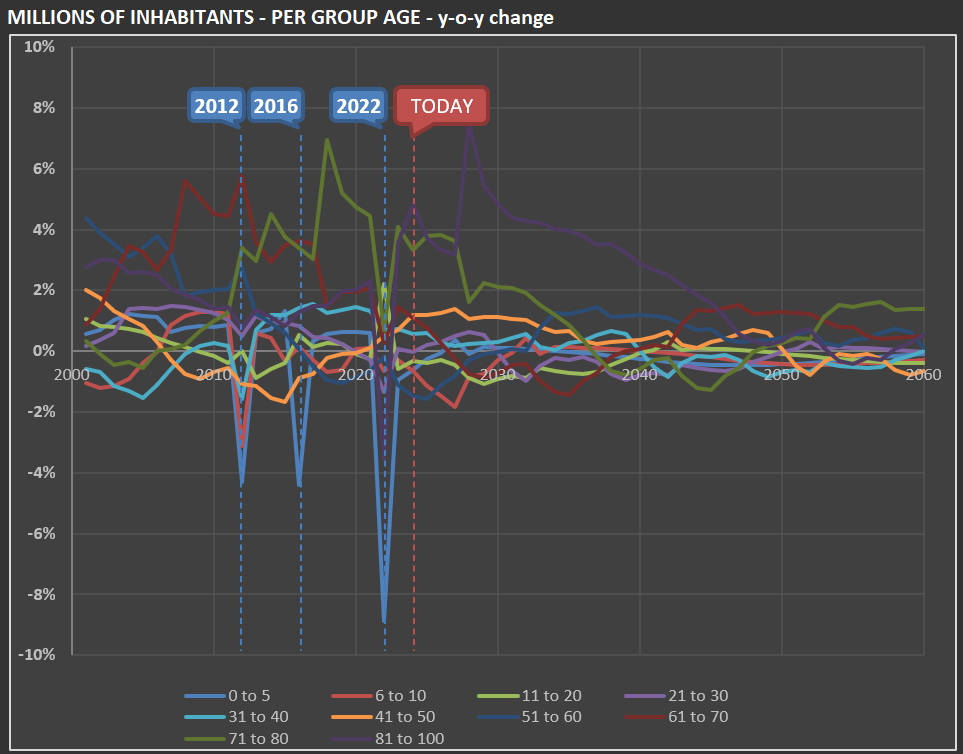

When I’m working on $CRI [Carter’s], I need to update the forecasted population growth for the “zero to 5” segment in the US (done by the US Census Bureau), as they are the company’s core “clients.” The first chart below shows—per various group ages—how many millions of people the US has had and is expected to have over the next few decades.

The yellow arrow highlights the “zero to 5” group. Just below it is the “6 to 10” group. Note that the US Census Bureau drops the number of young children in the US with each dataset revision. The second chart gives you an idea of how much: in 2022, the “zero to 5” group’s estimate was reduced by almost 9%!

Glass Half Full: OI's Strategic Pivot Promises Value Amid Historic Low P/E

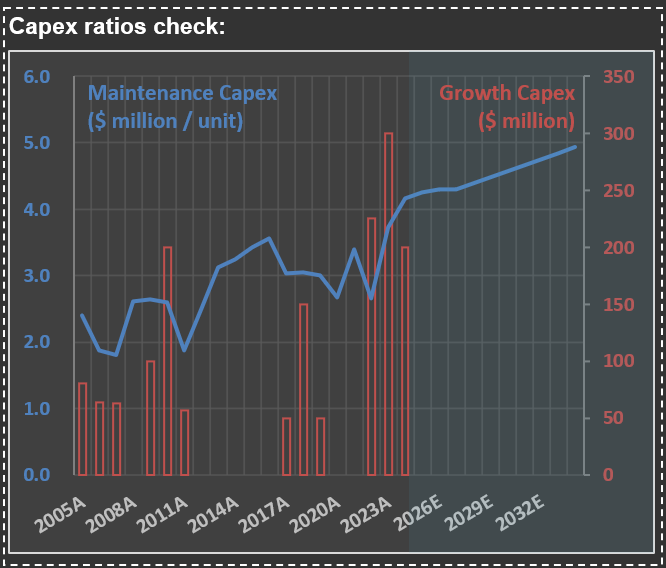

Never underestimate how much money CEOs can burn (and still be paid millions to do so!). Below is my check for Capex for $OI [OI-Glass], the biggest glass containers manufacturer in the world. The company battled massive asbestos liabilities for years. When that got solved, what was the prior CEO plan? Burn almost $1 billion (these are the sum of the two last groups of the red bars) in a new technology called MAGMA.

Here is what the new CEO just said about it: “With regard to MAGMA, we continue to ramp up production at our first greenfield line in Bowling Green, Kentucky. The achievement of key operating and financial milestones at this site over the course of 2025 will be critical as we chart the future of the MAGMA program. As we focus on these milestones at Bowling Green, we have paused the development of Generation 3. As with any capital project, MAGMA will be required to generate returns of at least WACC plus 2%. We will provide more details on our long-term strategic plan next month at our Investor Day.”

In other words, MAGMA didn’t work (as I’m assuming it doesn’t generate returns above WACC). So I will be in New York on March 14th - at the NYSE - to participate on the company’s Investor Day. I hope they will provide information that will increase investors confidence. As of now, if they achieve their $1.45 billion EBITDA guidance for 2017, it means that the company is trading at less than 3x P/E! I don’t use multiples to calculate fair values for companies at RIM. But such a low figure called my attention!

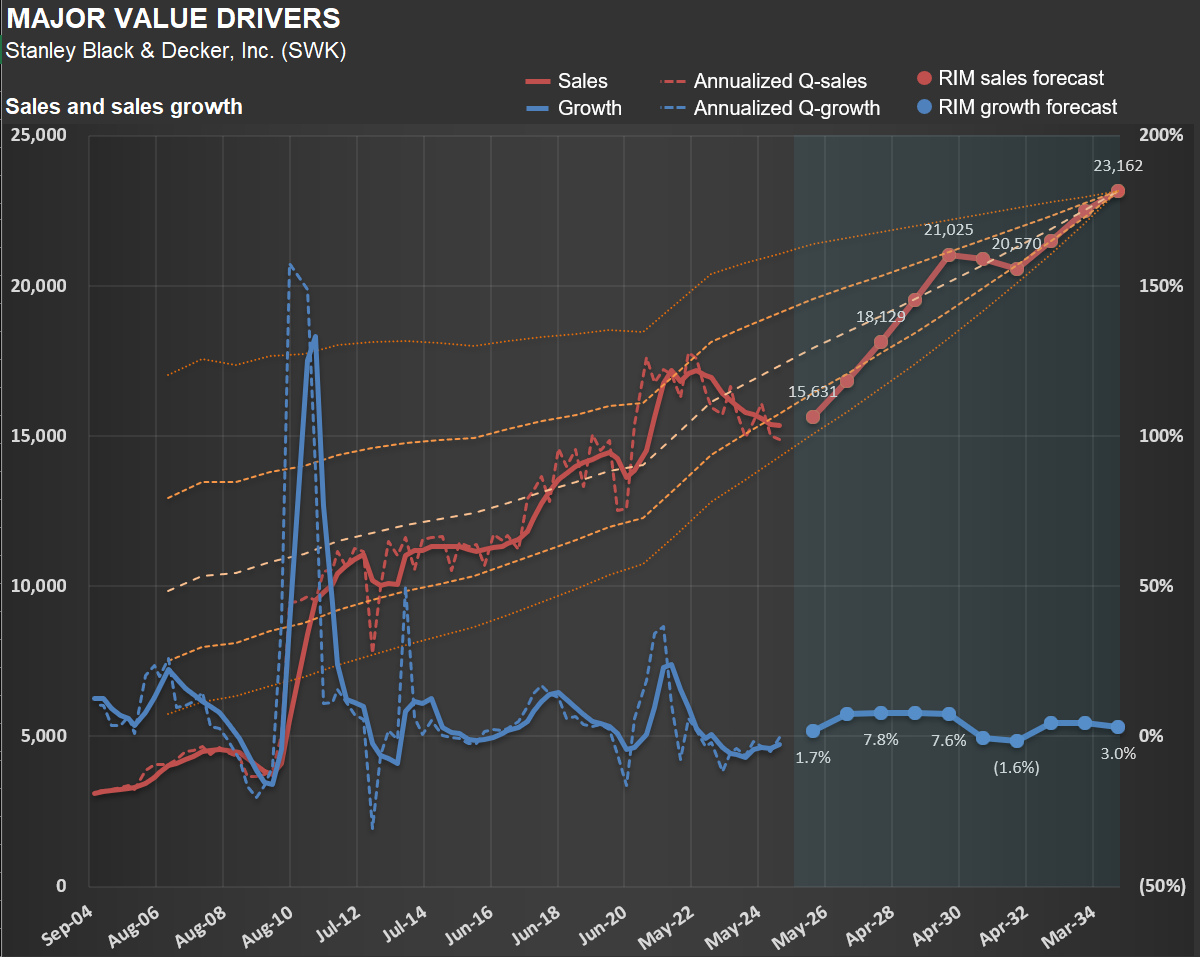

Stanley Black & Decker: Sales Slump and Margin Collapse in the Post-Stimulus Reality

The first picture below shows sales for $SWK (Stanley Black & Decker) - see how it is now below the mid-trendline (which includes the impact from inflation + population growth). The second picture shows margins - it is amazing how strongly impacted their margins were when it became clear that management misinterpreted the excessive stimulus of 2020/2021.

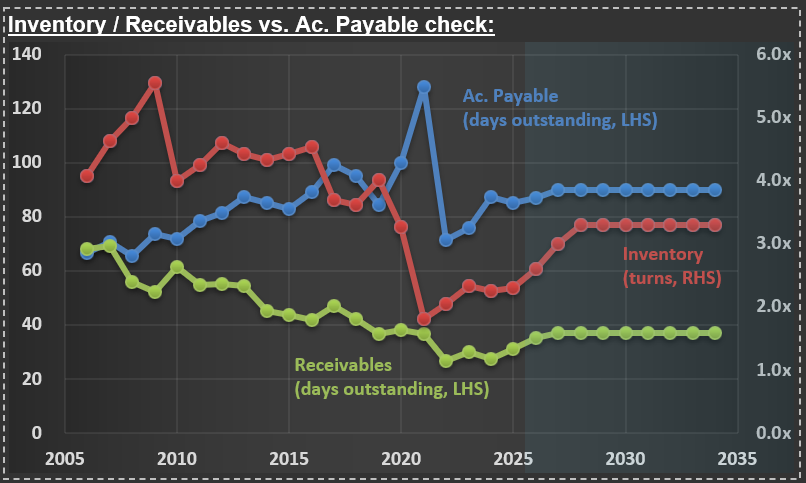

Stanley Black & Decker's Balance Sheet Battle: Unwinding Pandemic-Era Inventory Excesses

I’m working on $SWK [Stanley Black & Decker] today. It is incredible to see what the pandemic did to key lines of companies' balance sheets. The chart shows a massive drop in “inventory turns” (red line) in 2021, meaning that the company overproduced (and ordered excessively from manufacturing partners) tools and whatever it sold. They are bringing inventory to more normal levels, but it will be a multi-year exercise. Accounts Payable (blue line) are close to normal levels but look at the massive peak during the pandemic.

J.B. Hunt's Equipment Dilemma: Pandemic Expansion Meets Post-Boom Reality

Look at what $JBHT management said during the last conference call: “…we still have really significant capacity that’s underutilized. And the cost to store that equipment is a significant headwind for us. And so as we continue to scale and grow our volumes, while also improving pricing, that’s going to be our focus and our effort. The Walmart equipment, we reported – I think we reported just over 122,000 containers at the end of 4Q. When we onboarded the Walmart equipment, all of that equipment requires a modification and we haven’t completed that work. Clearly, we just did the acquisition in, I think, the second quarter of – or end of first quarter, second quarter last year. And that equipment is tucked away in storage right now because frankly, we’re still trying to grow into the 122,000 containers that you can see we own today.”

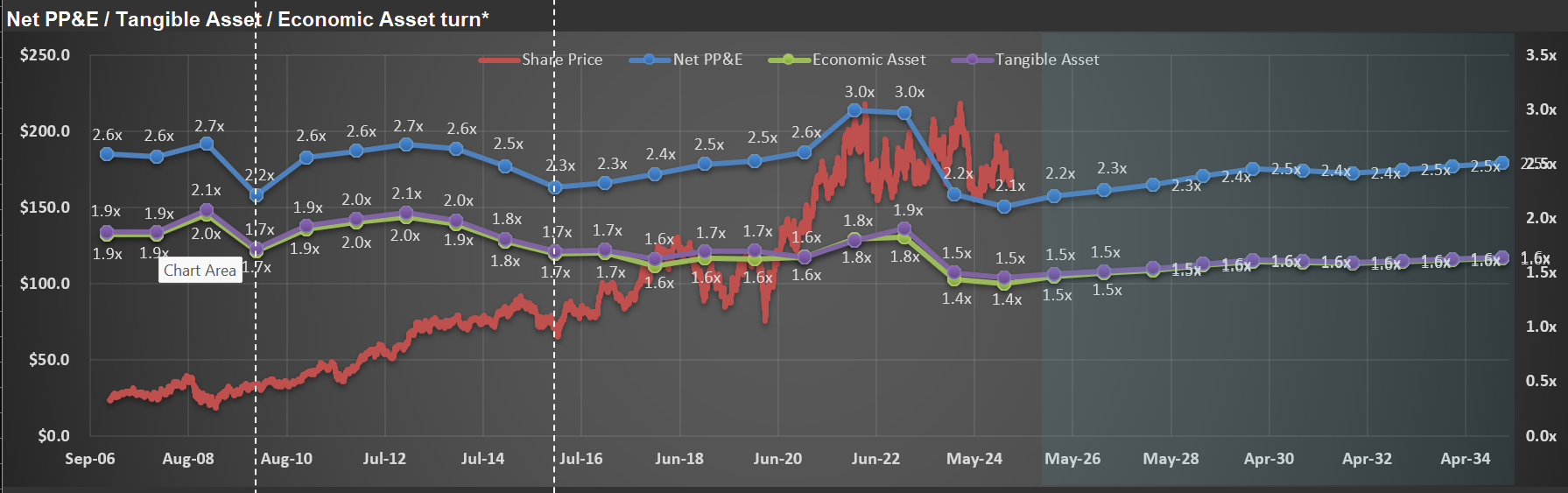

This was a classic over-investment situation, given the strong cycle for trucking companies during the pandemic (mostly on pricing, as companies were willing to pay anything to secure transportation capacity). The result: a very low “Net PP&E turnover”—see the blue line on the chart. It is as low as in the deep recession years of 2009.