Government Spending and Mortgage Rates: Understanding the Connection That Matters

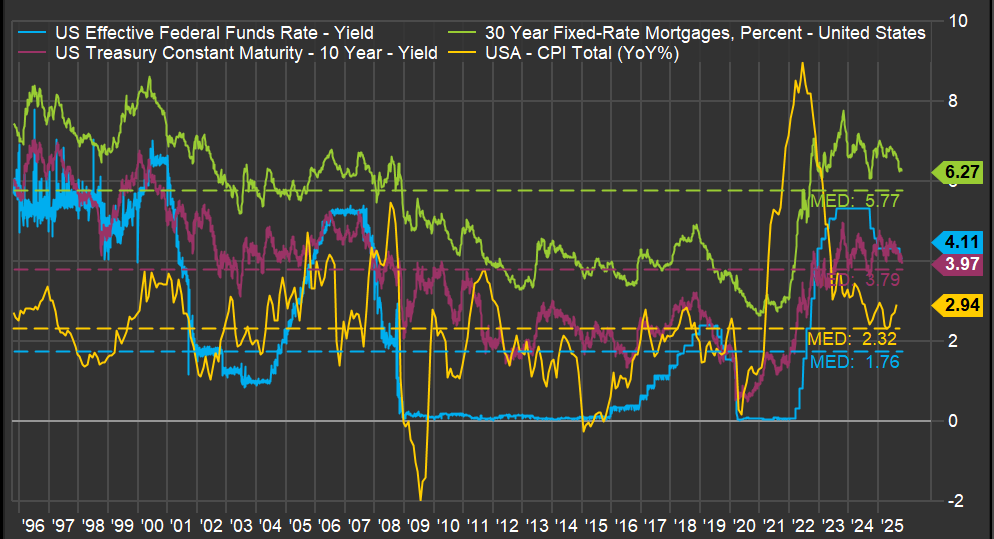

One of the key variables for the housing market is the 30-year mortgage rate. It isn’t uncommon to see posts on social media about the movement of such a rate in a single day. However, rates like this need to be viewed over a much longer timeframe. Below is a chart showing key series over three decades. In green is the 30-year mortgage rate. Note how it maintains a particular spread from the 10-year Treasury note (in magenta). Also interesting is the blue line—the Fed Funds Rate—which shows a more step-like pattern as the Federal Reserve uses it to achieve its dual mandate of inflation control and employment.

But the most critical line is the yellow one: inflation. A spike in inflation drove the jump in the 30-year mortgage rate, which had a profound impact on the existing home sales market, as I discussed in a previous post (here). But what caused such a sudden spike in inflation? The ferocious money-printing during the pandemic years.

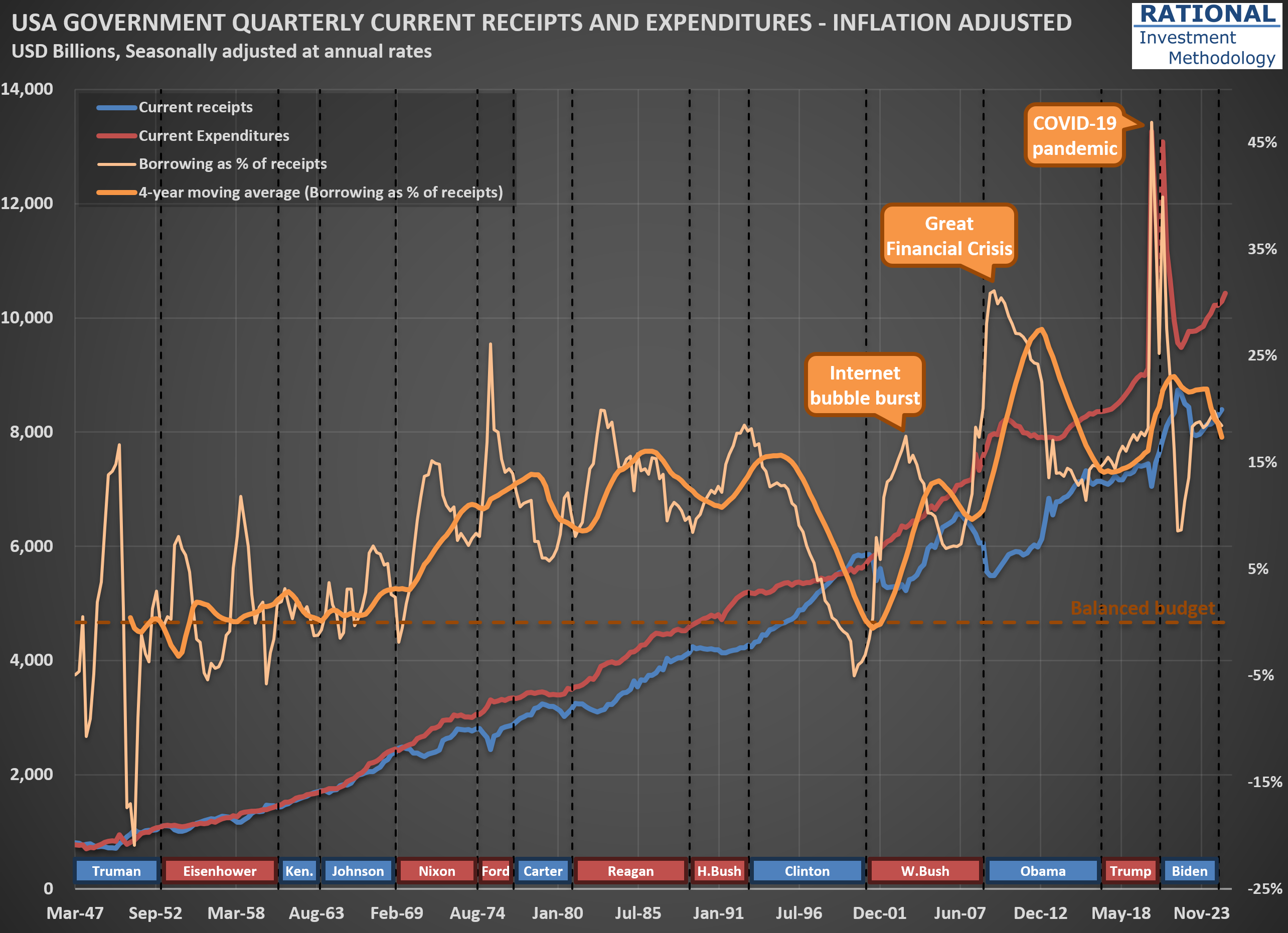

The question one needs to answer regarding the 30-year mortgage rate isn’t what it will do today, or even next year. The driver of all the lines you see in the first chart is how much the US government continues spending above its tax receipts. And the trend isn’t encouraging. The second chart shows (in orange) how much the US government has borrowed to cover its expenses, which include all transfers—think Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid. Note how spending increases with each crisis, with a massive 47% ratio (meaning the government spent 47% above its income) during the acute phase of the COVID-19 pandemic.

What is particularly concerning is that, apart from the late years of the Clinton administration when receipts increased substantially due to the internet bubble, the US has largely ignored fiscal discipline since the 1970s. One might argue, “Well, the US can do it because its currency is the global reserve.” However, no government in history has managed to abuse the monetary system indefinitely. The question is not “if” but “when” we will see stress on government bond yields. When that happens, the housing market will suffer significantly, and we will likely embark on another recession led by the housing market—which, as I’ve shown, has been part of many US economic crises (see here).

So what should an investor do? Focus on companies that, over decades, have navigated crises and emerged fully operational on the other side. Not necessarily unscathed—it is common for a company’s earnings to suffer during a recession—but healthy enough to continue business as usual after the storm passes. That is what I work on every day (for the past 20 years), spending countless hours running company-specific analyses. It isn’t fun or easy, but it is necessary.