CofC: Consumer Discretionary - Consumer Services

From Shorts to Opportunity: Tracking $SBUX's Turnaround Journey

$SBUX (Starbucks) finds itself in a turnaround phase, and management’s language on the latest conference call was telling. They repeatedly described this as the “early stages of our turnaround in the US”—part of a “multiyear effort” to “rebuild” and get “Back to Starbucks.” When executives use words like “rebuild,” it signals they’re addressing fundamental challenges rather than operating from a position of strength.

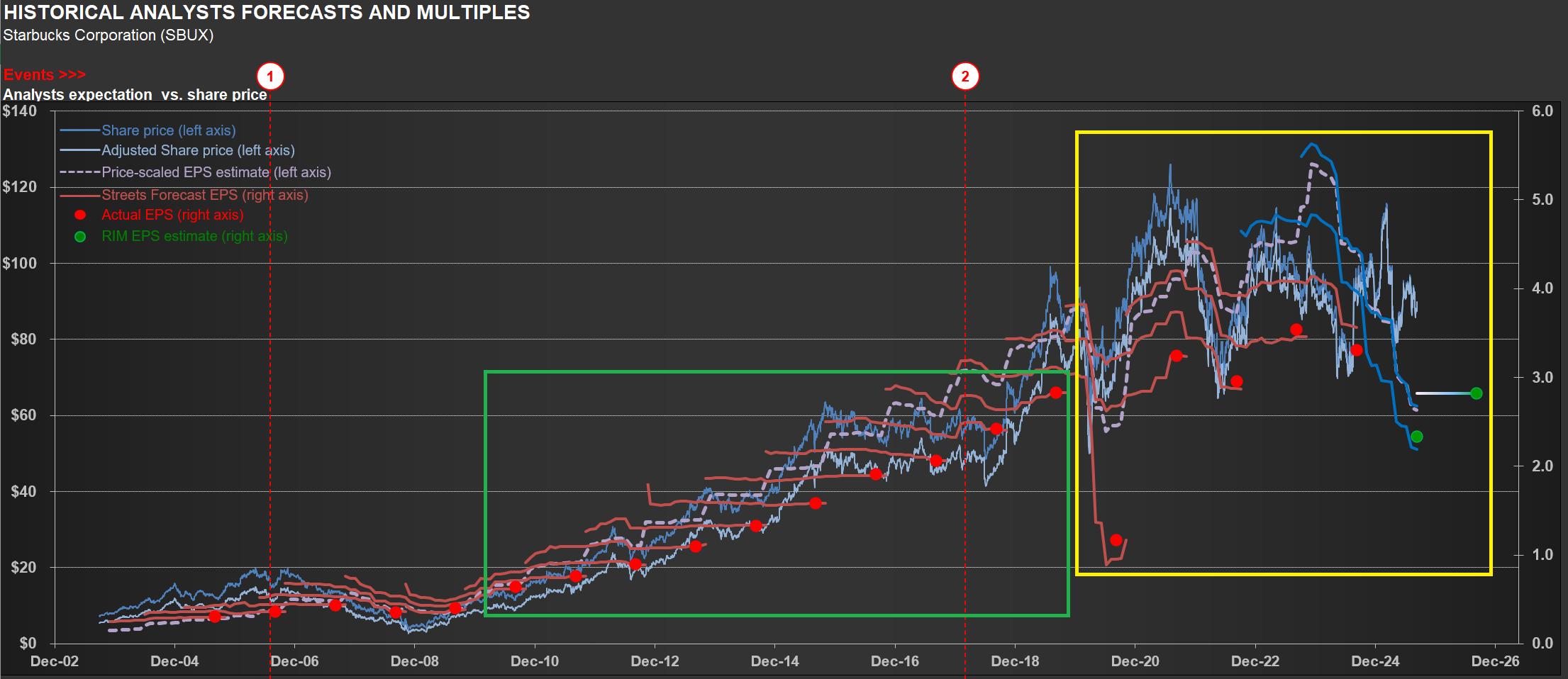

The company’s financials clearly reflect this reality. Take a look at the chart below—one you’ll recognize from my previous analyses. It tracks the company’s earnings versus share price over time. Notice how earnings estimates have become much more volatile recently (yellow rectangle) compared to the pre-pandemic, post-GFC period (green rectangle). While volatility during the pandemic’s peak was understandable, why the continued decline now?

The EPS drop stems primarily from significant operating margin contraction, driven by deleverage and substantial strategic investments in the “Back to Starbucks” initiative. Management describes this as a comprehensive plan aimed at transforming both the business and its culture—ultimately building a stronger, more resilient, and consistently growing company. Chairman and CEO Brian Niccol calls it “the right plan,” grounded in customer and partner feedback and rooted in the company’s core identity as a welcoming coffeehouse serving fine coffee handcrafted by skilled baristas.

But transformation comes with costs. The effort includes over $0.5 billion in additional labor hours for the Green Apron Service rollout and significant spending on Leadership Experience 2025—an event that brought together 14,000 coffeehouse leaders. Will it work? Time will tell, but we should expect continued volatility in earnings expectations along the way.

Here’s what makes this interesting from an investment perspective: if the turnaround succeeds, this volatility could create opportunities to acquire shares at a substantial margin of safety. The last time I owned $SBUX shares was back in 2009. My last three positions on the name were shorts—all successful trades, but that’s the past.

The key question now is whether management can execute on its vision while navigating the inevitable bumps ahead.

The Surprising Upside for $CHH (Choice Hotels) in a Soft Market

I’ve just finished updating my analysis on $CHH (Choice Hotels). The company franchises a wide range of hotel brands—including Comfort (Inn, Suites), Quality Inn, Econo Lodge, Rodeway Inn, Sleep Inn, Country Inn & Suites, Ascend Hotel Collection, Clarion (including Clarion Pointe), WoodSpring Suites, and MainStay Suites. These brands span the spectrum from economy to upscale. Altogether, CHH has nearly 8,000 properties, representing over 650,000 rooms.

On the most recent conference call, management was asked about the softness in leisure and lower-end chain scales—an outcome that runs counter to expectations of “trade-down” in a weaker economy. The CEO’s response was telling: in uncertain economic periods, Choice’s established brands with strong name recognition tend to attract more independent hotels looking to join a larger system.

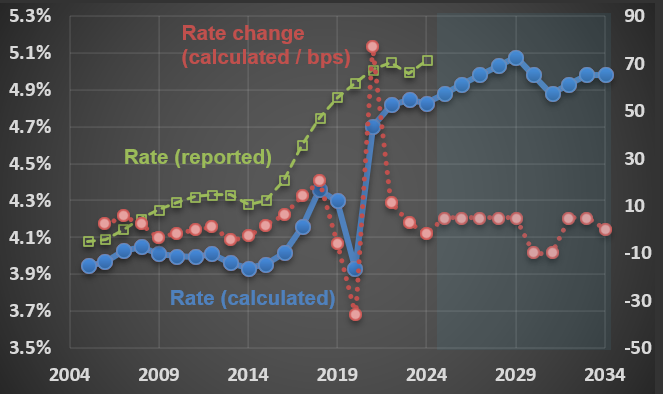

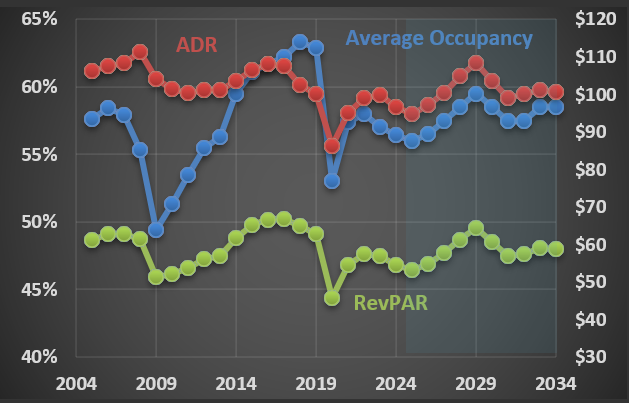

To illustrate just how much “economic times”—something no company can control—can affect business (sometimes positively), take a look at the first chart below. The blue line shows the actual royalty rate that CHH charges hotel owners to be part of its system. While Choice Hotels was already working to increase fees, it was able to raise them by about 25% (from ~4% to ~5%) almost instantly during the pandemic.

What stands out is that this increase in fees happened during a period when both average occupancy and ADR (Average Daily Rate) were lower than pre-pandemic levels (all figures in USD are adjusted for inflation). These two ratios combine to produce RevPAR (Revenue Per Available Room*), which remains below pre-pandemic years—nearly 20% lower in 2024 compared to 2017 (the peak year over the past two decades).

In other words, it wasn’t a boom in business that drove thousands of independent hotels to join the Choice system. Rather, Choice Hotels’ brands are strong enough that, even with significantly higher royalty fees than before the pandemic, the net return for hotel owners is still attractive.

[*] RevPAR = Occupancy x ADR

From Pizza to Tesla: When Founders Shape—and Shake—Brands

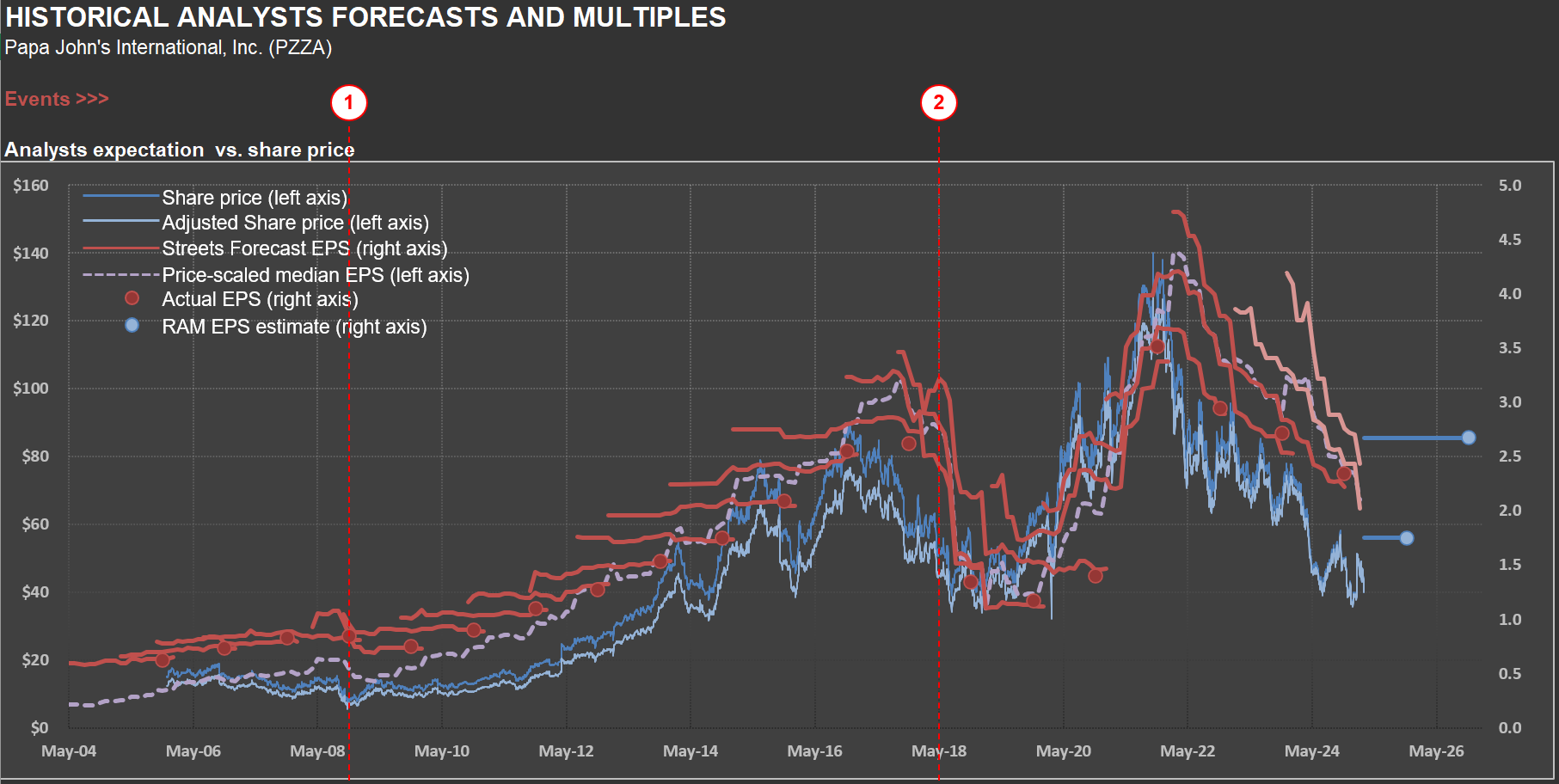

Every time I’m tempted to think a company has a straightforward business model, I revisit my analysis of $PZZA (Papa John’s). Selling pizza might seem simple, but the story behind this company proves otherwise. Below is a chart familiar to those who follow RIM’s approach, showing the correlation between share price and average sell-side analyst estimates. I’ve previously discussed how market prices are often biased by short-term EPS projections here.

Papa John’s earnings over the past decade have been anything but steady. The company was coming off a strong growth phase when its founder and former CEO, John Schnatter, made racially insensitive remarks during a May 2018 conference call. This scandal, revealed in a July Forbes article, triggered widespread backlash. Schnatter’s image was swiftly removed from the company’s branding and advertisements. Just days later, Forbes published another article detailing allegations of sexual harassment within Papa John’s offices. On the same day, Wendy’s announced it would not pursue a potential merger with Papa John’s.

Event #2 on the chart highlights the month leading up to these revelations. Sales plummeted, dragging earnings—and share prices—down with them. The company faced an uphill battle to distance itself from Schnatter’s legacy when an unexpected twist changed its fortunes: the pandemic. As restaurants closed nationwide, pizza delivery became one of the few ways people could enjoy prepared meals at home—a small slice of normalcy for many during uncertain times. Sales surged, margins improved, and EPS hit new highs. The founder’s scandal faded into history.

Fast-forward to today: Papa John’s is grappling with more challenges. Sales are normalizing after their pandemic peak, and the broader consumer environment remains weak—something I’ve touched on in recent posts about the recessionary pressures facing American consumers. Even for a seemingly simple business like pizza, there’s no such thing as “normal.”

This brings me to $TSLA (Tesla) and Elon Musk—a case study in what might be called “key man risk” on steroids. Much like Papa John’s in 2018-2019, Tesla is deeply tied to its founder’s vision and personality. Founders often drive rapid growth because they care deeply about their creations. But when their actions alienate customers—whether justified or not—the fallout can be significant. From pizzas to electric cars, businesses are far more intricate than they appear at first glance. And when emotions start influencing a brand, complexity grows exponentially.