CofC: Materials - Materials

Forecasting $EXP Sales: How Home Starts and Industry Behavior Intersect

Sometimes clients wonder why I devote so much time to producing (and updating) a wide array of industry-wide analyses. For example, you’ve likely seen the posts I’ve published covering the housing (here) or transportation (here) sectors. The reason is simple: industry dynamics are typically the critical force shaping sales for any individual company.

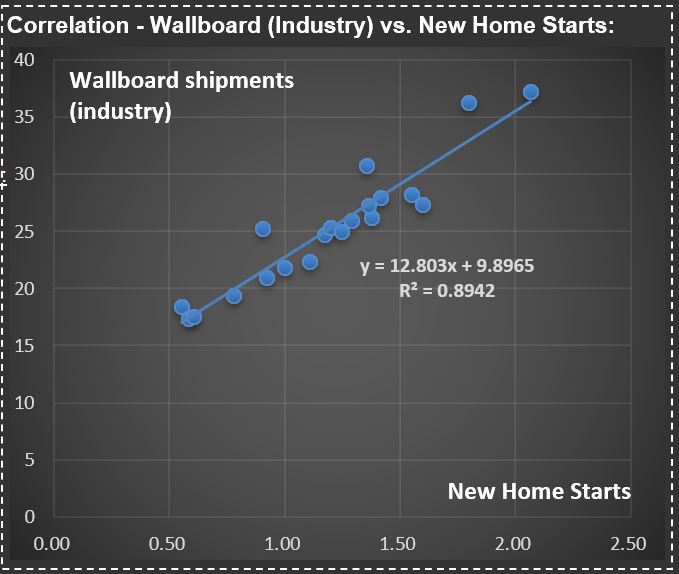

Take today’s focus: $EXP (Eagle Materials), a leading U.S. producer of wallboard and cement, with additional operations in concrete and aggregates. See the first scatter plot.  It highlights the strong correlation between U.S. wallboard sales and new home starts (that is, newly constructed houses). While not all wallboard goes into new housing, this single variable explains nearly 90% of total sales, reflecting the interconnectedness of adjacent areas within the housing complex.

It highlights the strong correlation between U.S. wallboard sales and new home starts (that is, newly constructed houses). While not all wallboard goes into new housing, this single variable explains nearly 90% of total sales, reflecting the interconnectedness of adjacent areas within the housing complex.

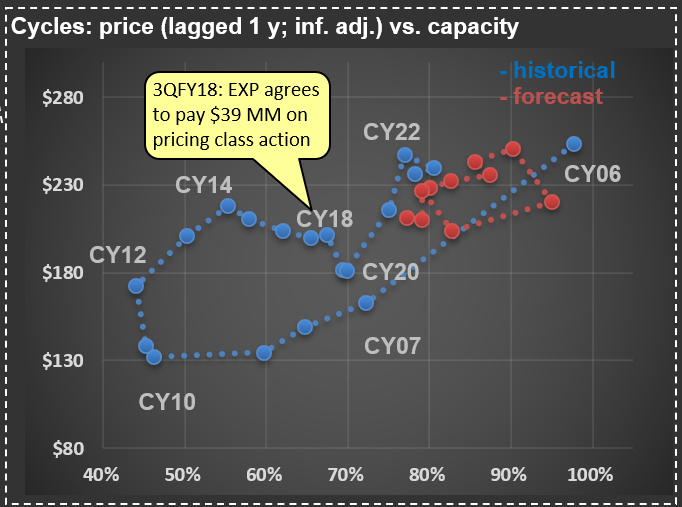

This is why understanding the cycles of new home starts in the U.S. is essential for accurately forecasting sales for Eagle Materials’ wallboard segment. From there, it’s a straightforward process to estimate $EXP’s market share and, with further analysis, explore the dynamics between capacity utilization and wallboard pricing—take a look at the second chart for a visual depiction.

During the mid-2000s housing boom, capacity utilization at $EXP and its competitors reached very high levels (as did the price of wallboard). As the cycle turned and housing starts collapsed, utilization rates dropped—and prices followed. Then, something unusual happened: in the early 2010s, wallboard prices climbed sharply, even though the industry’s fundamentals seemed weak. For a while, my analysis questioned its relevance—until, almost a decade later, Eagle Materials (along with USG, the market leader) was fined tens of millions of dollars in a class action for price-fixing. In short, the major players had been colluding.

Looking ahead, pricing should remain relatively disciplined, especially with fewer homes expected to be built in the coming years (see my recent analysis on U.S. Census Bureau data and future new home starts - here). That said, if significant industry players resume collusive behavior, all bets are off—so I’ll be keeping a close eye on price developments in this segment.

Navigating Cycles: Insights from $OLN’s Volatile Industry

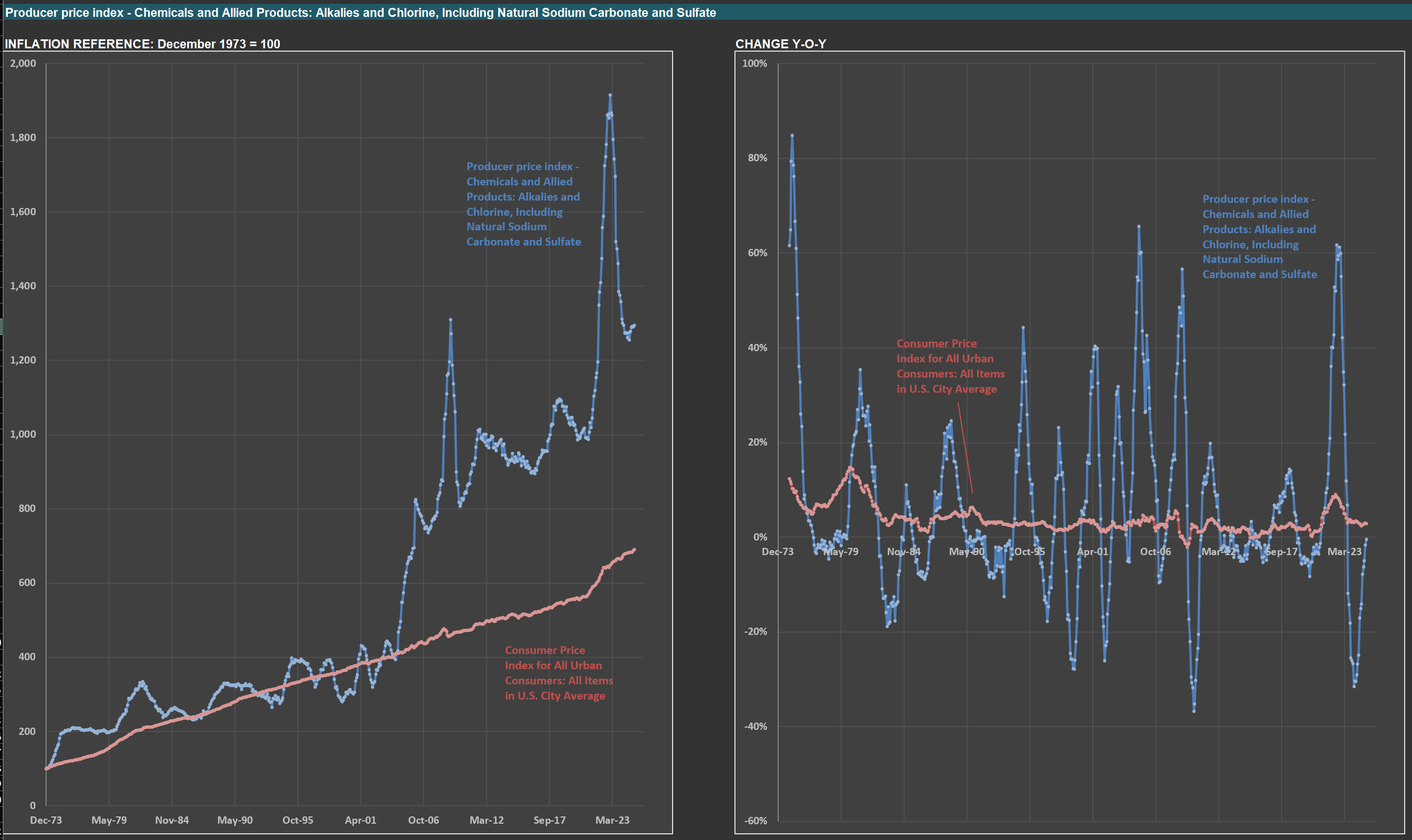

Today, I’m analyzing $OLN (Olin), a company specializing in chlorine, caustic soda, vinyls, and other chlorinated organics, as well as epoxy materials and their precursors. The charts below illustrate the challenges of operating in a cyclical industry—and what that means for investors.

On the left, you’ll see a price index for alkalies and chlorine (in blue), $OLN’s core product category, alongside a broad consumer price index (in red). On the right, the year-over-year changes for both series are displayed. The stark variability in commodity prices compared to broader price indexes is evident. The most recent spike was driven by two factors: heightened consumption during the pandemic—fueled by oversized government stimulus—and a fire at a major U.S. plant producing similar chemicals.

This volatility highlights how challenging it is to manage a business in such an environment. For investors, however, there’s an upside. These sharp price and volume swings can significantly impact $OLN’s profitability, leading to fluctuations in EPS and stock prices. For those willing to put in the work, these cycles create opportunities to buy or sell with a meaningful “margin of safety.” Of course, understanding these dynamics requires careful analysis and a great deal of patience.

$SEE’s Product Care Segment: A Warning Sign and The Market's Overreaction

$SEE (Sealed Air) is a name you’re likely familiar with, even if you don’t realize it. They’re the company behind Bubble Wrap—the iconic packaging material that’s as fun to pop as it is practical. Beyond Bubble Wrap, SEE provides materials and machines that streamline packaging processes across industries. If you’ve purchased food or products recently, chances are they were packaged using SEE’s solutions. You can find more examples of their offerings on their website.

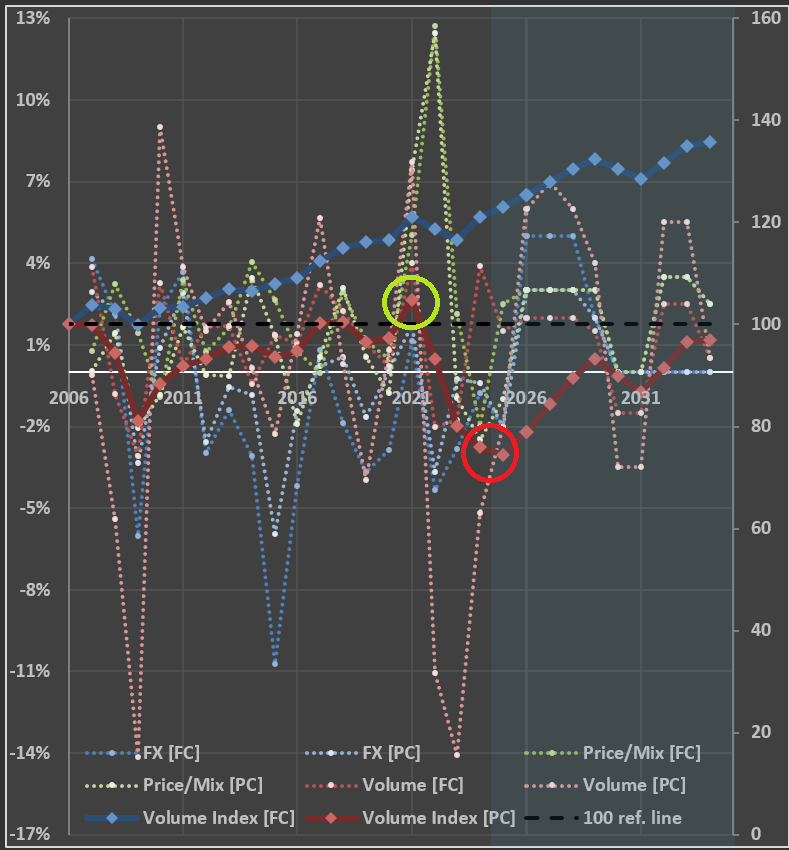

Take a look at the chart below, which breaks down key metrics for SEE’s two segments: Product Care [PC] and Food Care [FC]. The dotted lines represent the impact of volume, price, and foreign exchange (FX) on sales. Meanwhile, the solid lines show cumulative volume indices for both segments (2006 = 100).

The blue line for Food Care reflects stability—no major surprises there. But the dark red line for Product Care tells a different story. After recovering from the lows of 2009, there was a modest uptick in 2021 (highlighted by the green circle), driven by pandemic-era stimulus. However, the red circle draws attention to concerning figures for 2024 and projected 2025. The index for Product Care volume is around 75—25% below its 2006 level (two decades ago) and even lower than the 81 seen in 2009.

This decline raises important questions. Packaging products and equipment is undoubtedly a competitive space, but SEE remains a key player in the industry. The drop in Product Care volume seems less likely to stem from a sudden loss of market share and more likely to signal broader economic trends—perhaps another indicator of a consumer recession. Despite this, the market appears to have punished SEE’s valuation, focusing narrowly on its current depressed earnings per share (EPS). Could this reaction be overly pessimistic?

Where Did the Cash from Operations Go?

Today, I’m diving into my analysis of $PKG (Packaging Corporation of America), a company that offers an interesting case study in how businesses deploy their cash beyond dividends and share buybacks. One common strategy is acquiring other businesses, typically within the same industry. This approach aligns with the broader trend in the U.S., a country I often refer to as “the land of oligopolies,” where many industries are dominated by a handful of major players. However, not all acquisitions are created equal—some management teams venture outside their area of expertise, attempting to diversify into uncorrelated industries. These moves frequently result in losses.

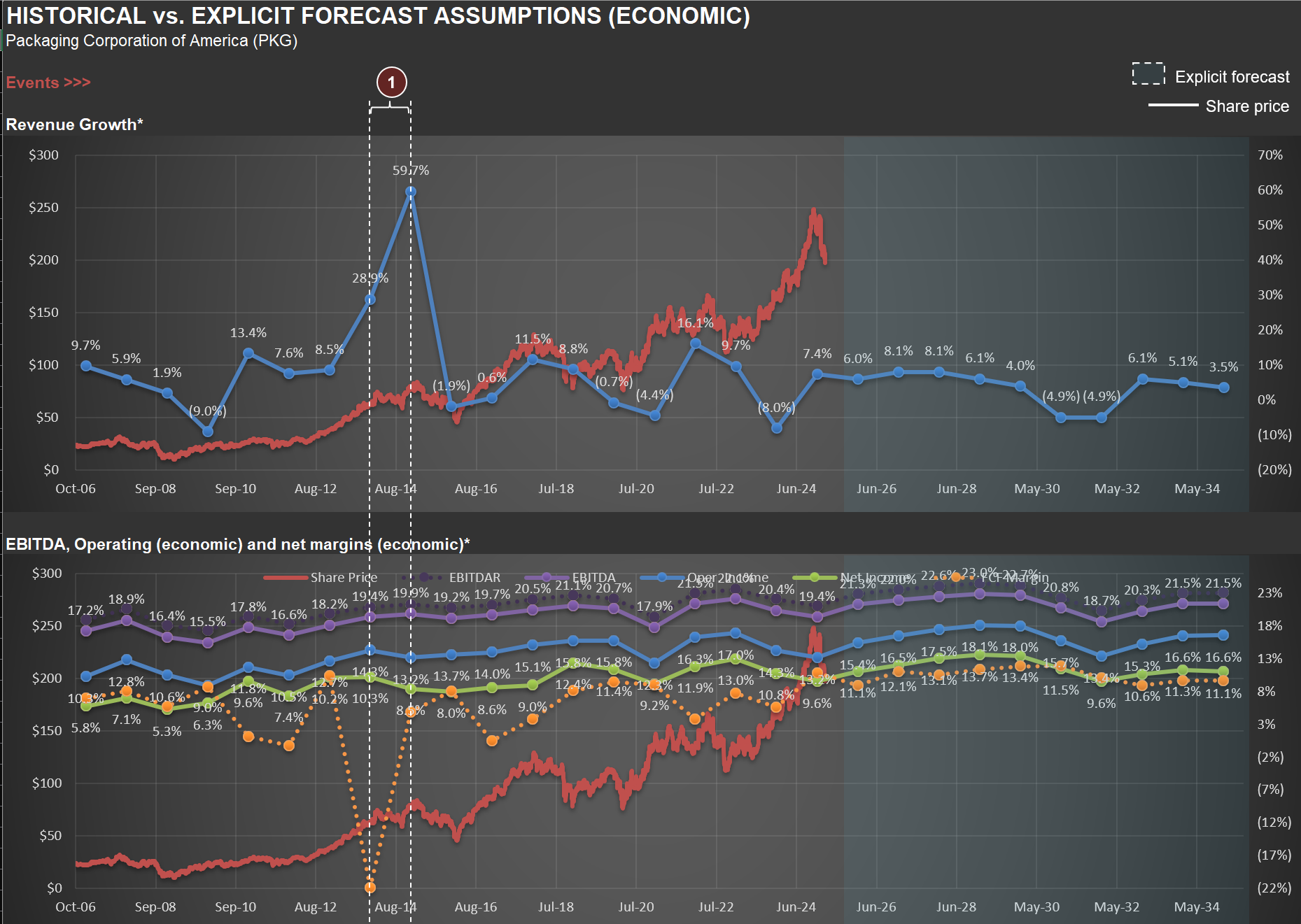

In contrast, PKG’s management opted for a more logical and focused strategy. In late 2013, they acquired Boise Inc., another paper and packaging company, for $1.3 billion. Since then, PKG has made additional acquisitions within its core industry, albeit at smaller scales.

The two charts below illustrate the impact of the Boise acquisition on PKG’s financials. The first chart highlights a notable surge in sales growth over the two years following the deal’s closure. This increase reflects the integration of Boise’s sales into PKG’s financials. The second chart shows a significant negative Free Cash Flow (FCF) margin during this period. FCF margin is calculated as (i) Net Cash from Operating Activities minus (ii) Net Cash from Investing Activities, divided by (iii) Sales.

The $1.3 billion spent on Boise is captured under “Net Cash from Investing Activities” pushing the total figure into negative territory. The key question is whether this acquisition will ultimately pay off—a question that demands detailed valuation work. After assessing the rationale behind a deal, it’s essential to adjust future projections to account for the new assets and business operations.

Getting this process right increases your chances of buying or selling a company at prices aligned with your investment thesis—whether long or short. Missing critical details or skipping a robust forecast can lead to mediocre performance at best. And if you happen to make money despite a flawed forecast? Recognize it for what it is: luck.

At its core, the job of an investment manager is to minimize reliance on luck by rigorously analyzing and projecting logical outcomes. Yet even when your analysis is spot on, patience and discipline are vital—it can take years for your thesis to play out fully.

Fundamental Analysis Spotlight: $OI and Market Mispricing

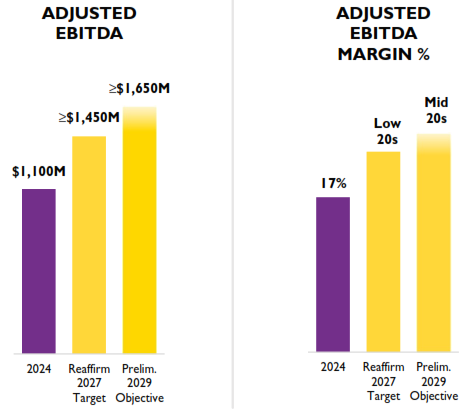

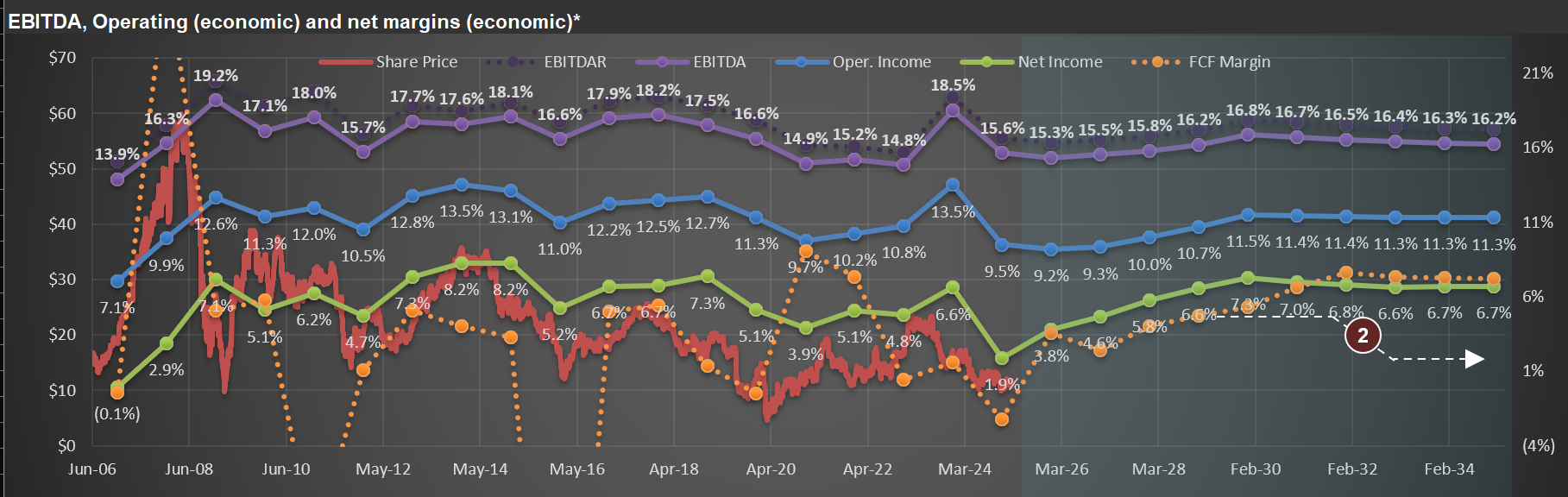

I attended the $OI (OI-Glass) investor day event and wanted to share some interesting insights. Look at the first chart below, which I pulled from their extensive 91-page presentation. Notice the projections for 2029: management targets EBITDA margins in the “mid 20s,” so let’s call it “around 25%.”

Now, check out the second image—this one shows my base-case scenario for OI-Glass. By 2029, my estimated EBITDA margin stands at 16.8%. I’m slightly more conservative in calculating EBITDA than management, as I leave some expenses on my calculations that they might exclude. So let’s round up my estimate to 17%.

But here’s the impressive part: OI-Glass appears substantially undervalued even using my conservative margin of 17% (or 8 percentage points below management’s target). Historically, the market has valued companies similar to OI-Glass—assuming my base-case scenario—at around 4 to 5 times today’s valuation. It would be much more with EBITDA margins of 25%!

This is a perfect illustration of market inefficiencies. The market isn’t fully pricing future profitability improvements implied by OI-Glass management’s expectations. Instead, share prices often reflect current EPS disproportionately. This is precisely where fundamental analysis adds value. If you’re skilled at (and have the time to dedicate to) understanding businesses and accurately forecasting long-term earnings potential, you’ll be well-positioned to identify opportunities (long or short) that eventually get recognized by the Market’s mechanical pricing heuristics.

Hence, I focus on first understanding what companies do and in which context (e.g., their competitive environment). Only after that do I spend time modeling a company in excruciating detail (also a necessary step to quantify your understanding of the business). With such an approach, I hope to be an “investor” and not a “speculator " (who blindly hopes that share prices move in their favor).

Glass Half Full: OI's Strategic Pivot Promises Value Amid Historic Low P/E

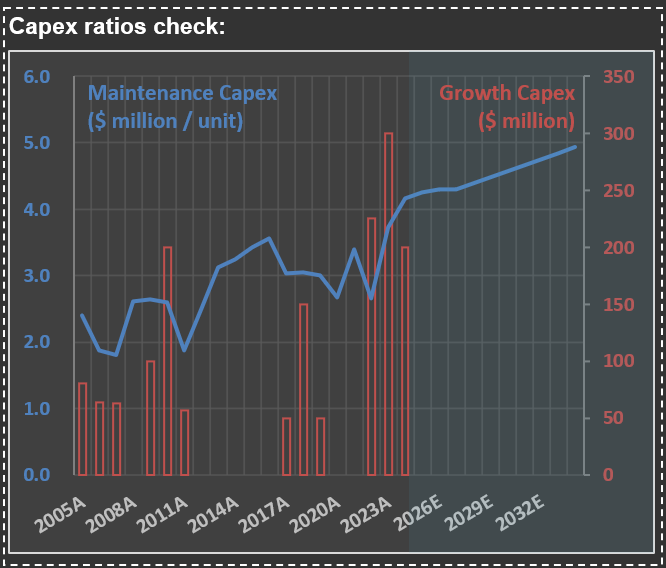

Never underestimate how much money CEOs can burn (and still be paid millions to do so!). Below is my check for Capex for $OI [OI-Glass], the biggest glass containers manufacturer in the world. The company battled massive asbestos liabilities for years. When that got solved, what was the prior CEO plan? Burn almost $1 billion (these are the sum of the two last groups of the red bars) in a new technology called MAGMA.

Here is what the new CEO just said about it: “With regard to MAGMA, we continue to ramp up production at our first greenfield line in Bowling Green, Kentucky. The achievement of key operating and financial milestones at this site over the course of 2025 will be critical as we chart the future of the MAGMA program. As we focus on these milestones at Bowling Green, we have paused the development of Generation 3. As with any capital project, MAGMA will be required to generate returns of at least WACC plus 2%. We will provide more details on our long-term strategic plan next month at our Investor Day.”

In other words, MAGMA didn’t work (as I’m assuming it doesn’t generate returns above WACC). So I will be in New York on March 14th - at the NYSE - to participate on the company’s Investor Day. I hope they will provide information that will increase investors confidence. As of now, if they achieve their $1.45 billion EBITDA guidance for 2017, it means that the company is trading at less than 3x P/E! I don’t use multiples to calculate fair values for companies at RIM. But such a low figure called my attention!