CofC: Consumer Discretionary - Retailing

Cross-Checking Industry Trends: Lowe’s and Home Depot

The reason I follow multiple companies within the same industry is, among other things, to cross-check whether trends observed in one company are also evident in another. For example, take a look at the chart below, which illustrates $LOW (Lowe’s) sales per square foot. Focus on the green series—it represents sales adjusted for inflation and square footage growth. The adjustment for square footage growth is less significant now, as Lowe’s (and Home Depot) have largely saturated their markets. The second chart, which shows year-over-year sales per square foot, highlights the extraordinary growth in 2020—nearly 24%.

Now, compare this with what I recently wrote about $HD (Home Depot) (here). In the top chart, you’ll see a similar series for Home Depot’s sales adjusted for inflation and square footage growth (in red). Notice how closely the patterns align between the two companies?

These similarities suggest that both Lowe’s and Home Depot were impacted by the same macroeconomic trends during the pandemic. This indicates that neither company’s management was implementing uniquely effective strategies to drive sales during that period. Instead, the rapid growth was fueled by pandemic-related excesses, which are now tapering off.

Looking ahead, it’s a matter of waiting for the next unusual factor—whether positive or negative—that will influence sales. However, what truly matters when conducting meaningful analysis is finding arguments to support a long-term perspective. In the case of Lowe’s and Home Depot, understanding their market saturation is key. Spectacular growth is likely a thing of the past for both companies.

Benjamin Graham's Wisdom Applied: Why I Differ on $HD

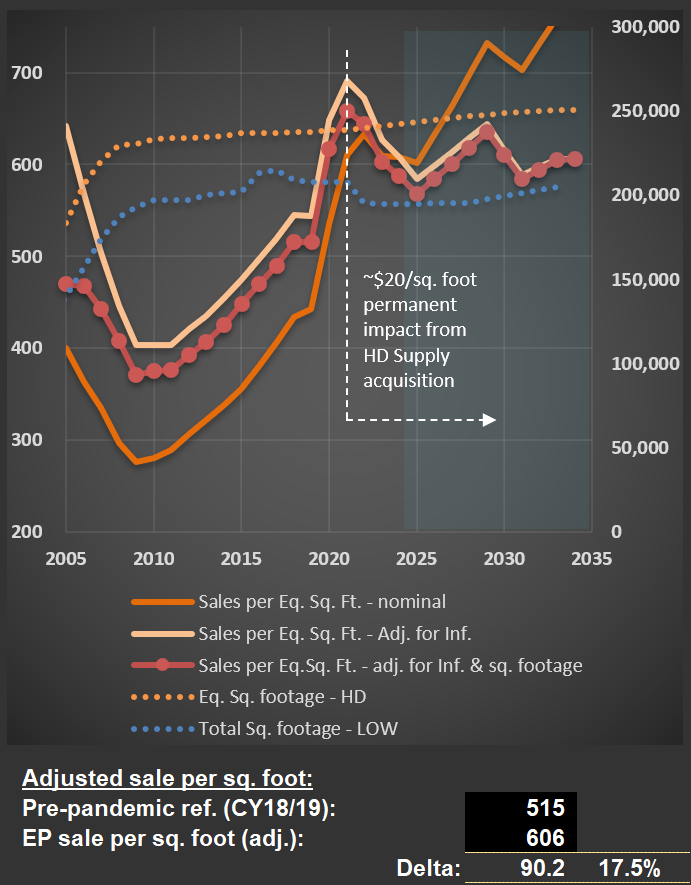

I just finished updating my analysis on $HD (Home Depot), and the outlook for 2025 suggests it will mark the fourth consecutive year of declining sales per square foot, adjusted for inflation. The last comparable period of sustained decline was between 2006 and 2009. You can see this trend clearly in the chart below—focus on the red data series with dots.

This decline reflects the normalization following the post-pandemic boom. During that period, extremely low interest rates, substantial stimulus measures, and increased time spent at home drove a surge in sales for Home Depot and $LOW (Lowe’s). Even factoring in the additional $20 per square foot from Home Depot’s acquisition of HD Supply, my analysis assumes average sales will remain about $70 higher than pre-pandemic levels (see calculations below the first chart). I also assume (not shown in the charts) that the company will maintain healthy margins. I.e., if anything, I’m being aggressive in my forecasts.

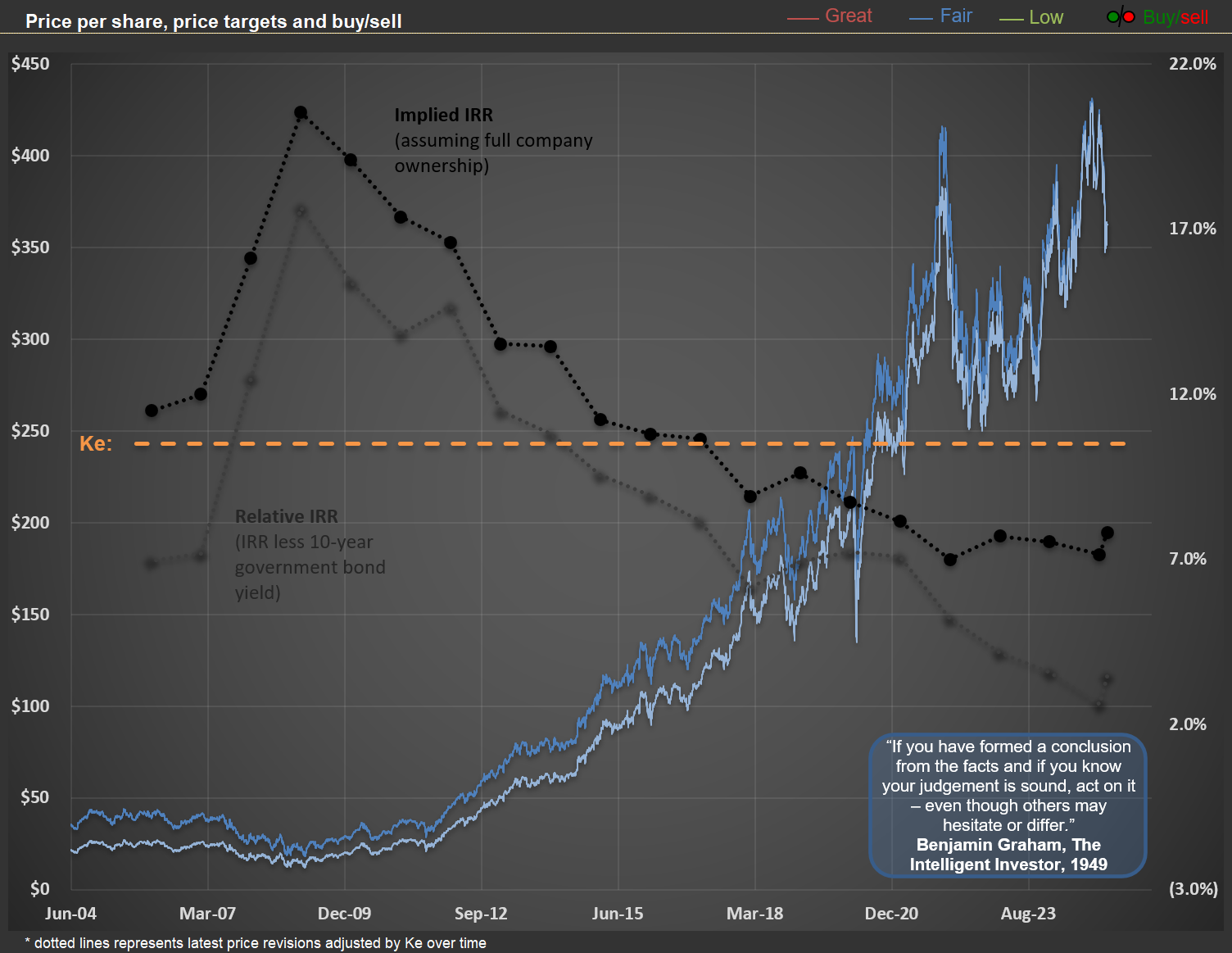

Despite this relatively optimistic assumption regarding future sales and margins, current share prices for HD suggest that long-term investors may achieve modest returns. Based on my base-case scenario, the future IRR (Internal Rate of Return) is projected to be approximately 7% per year. For context, you can read my earlier post on understanding implicit IRRs here.

The second chart below illustrates implicit IRRs for HD at 20 different year-end points. As expected, higher share prices correspond to lower IRRs—this is simply math. If your base-case scenario is well-calibrated, any given share price implies a specific IRR for long-term owners. Historically, the best time to buy HD (and LOW) shares was in 2009, when the implied IRR reached 20.5%. For perspective, this offered a real return (assuming an annual inflation rate of 2.5%) equivalent to multiplying your investment by five over a decade. I presented this analysis at a Value Investing Event in Trani, Italy, although few attendees were enthusiastic about these ideas at the time.

Today’s elevated prices prompt me to recall Benjamin Graham’s timeless advice from The Intelligent Investor, written in 1949: “If you have formed a conclusion from the facts and if you know your judgement is sound, act on it – even though others may hesitate or differ.” In contrast to many analysts nowadays, I believe $HD and $LOW are not attractive investments at current valuations. If sales continue to decline or fail to rebound meaningfully, perhaps the market will eventually acknowledge that these prices imply lower-than-deserved returns for holding these assets.

Are Investors Overpaying for Growth? O'Reilly's SSS Under the Microscope

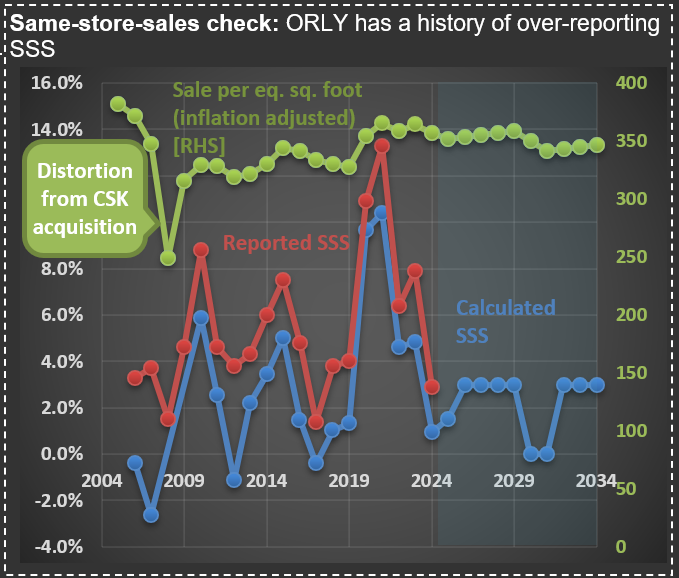

When analyzing retailers' sales, it is necessary to adjust “same-store sales” (SSS) by the age of the square footage. This adjustment is required because newer stores typically generate lower sales per square foot than established locations, as it takes time for customers to discover and frequent newly opened convenient locations.

Without these adjustments, there’s a significant risk of overestimating actual sales growth. In my analysis of $ORLY (O’Reilly Automotive), I’ve consistently calculated lower growth figures than what they’ve reported for several years now. As you can see in the picture below, ORLY’s reported figures (red line) consistently outpace the properly adjusted metrics (blue line).

Over the past two decades, ORLY has reported impressive average SSS growth of 5.6% annually. However, my calculations suggest they’ve overestimated this growth by approximately 2.9% per year. This means their true SSS growth rate is closer to 2.7%—essentially tracking with inflation.

This discrepancy may have contributed to ORLY’s current valuation, which stands at more than 30x earnings. At today’s price, an investor is accepting a potential return of only about 5.5% annually (from a business owner’s perspective, similar to how Warren Buffett would evaluate a complete acquisition). Is such a modest return sufficient for your investment goals?

Less cars but higher sales in real terms? Inflation confusion at play

After finishing my $AAP (Advance Auto Parts) work, I’m updating my analysis on $ORLY (O’Reilly Automotive). The difference in performance between these two stocks is staggering, but—given current price levels—you might be surprised which offers materially better prospects for higher IRRs (Internal Rate of Return) for the long-term holder.

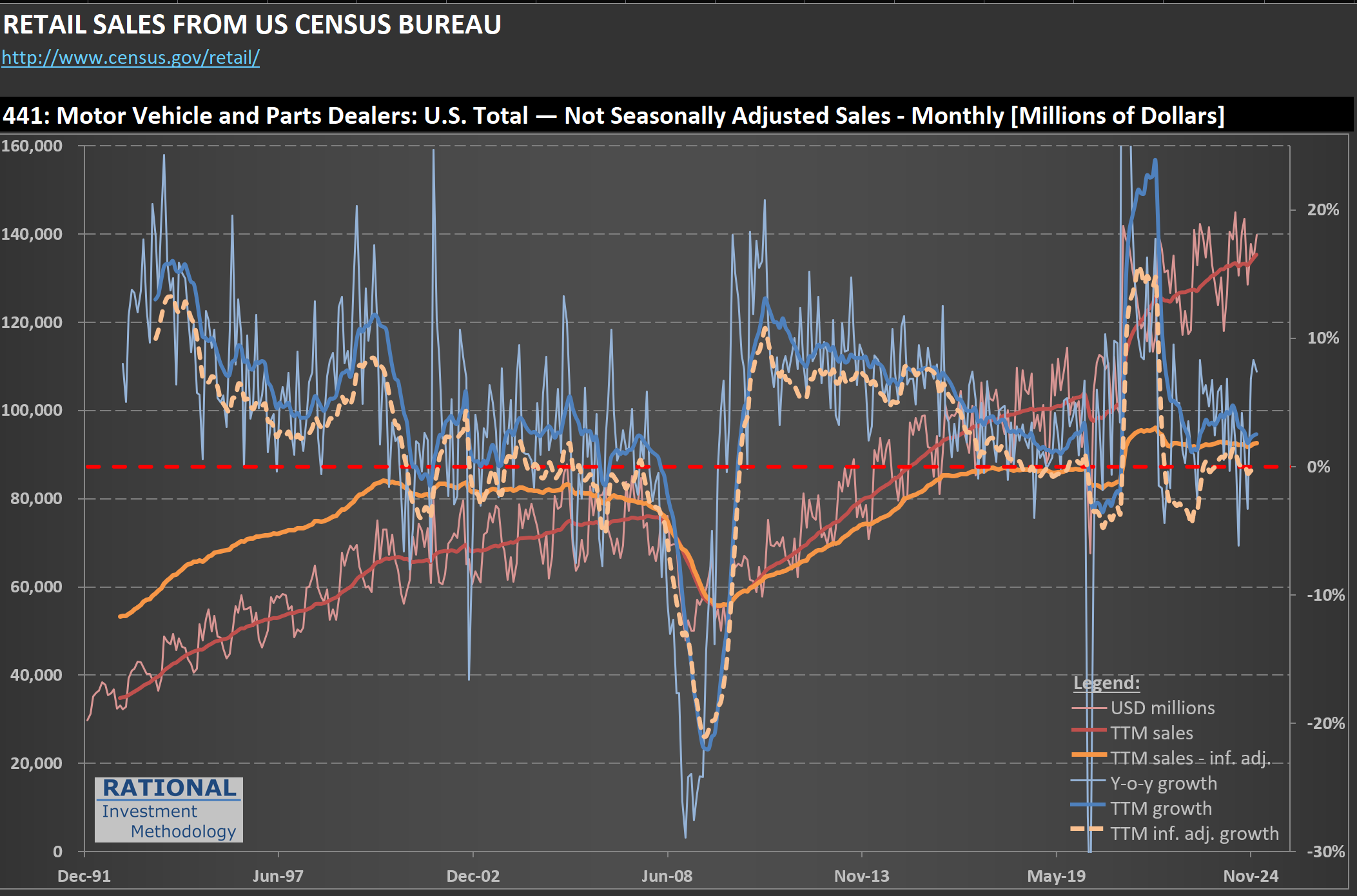

The chart I’m sharing below offers a high-level view of motor vehicle (and parts—a small part of these figures) sales. The line to focus on is the orange one: it shows sales adjusted for inflation. Now if you look at the last post (here) showing the number of vehicle sales, you will see a discrepancy. I.e., the number of vehicle sales is lower (by -7,5%) while the total dollars spent is higher (by +6.4%) compared to pre-pandemic levels.

A change in mix (more expensive cars, less cheap cars) could explain part of the delta. But another factor is at play: the overall inflation ratio (which I use to normalize sales) doesn’t capture the actual inflation in car prices. These more expensive (in real terms) cars lead to lower unit sales than before. It doesn’t help that the American consumer is also in a recession - I discussed it on a post yesterday (here).

Understanding long-term drivers for auto parts sales

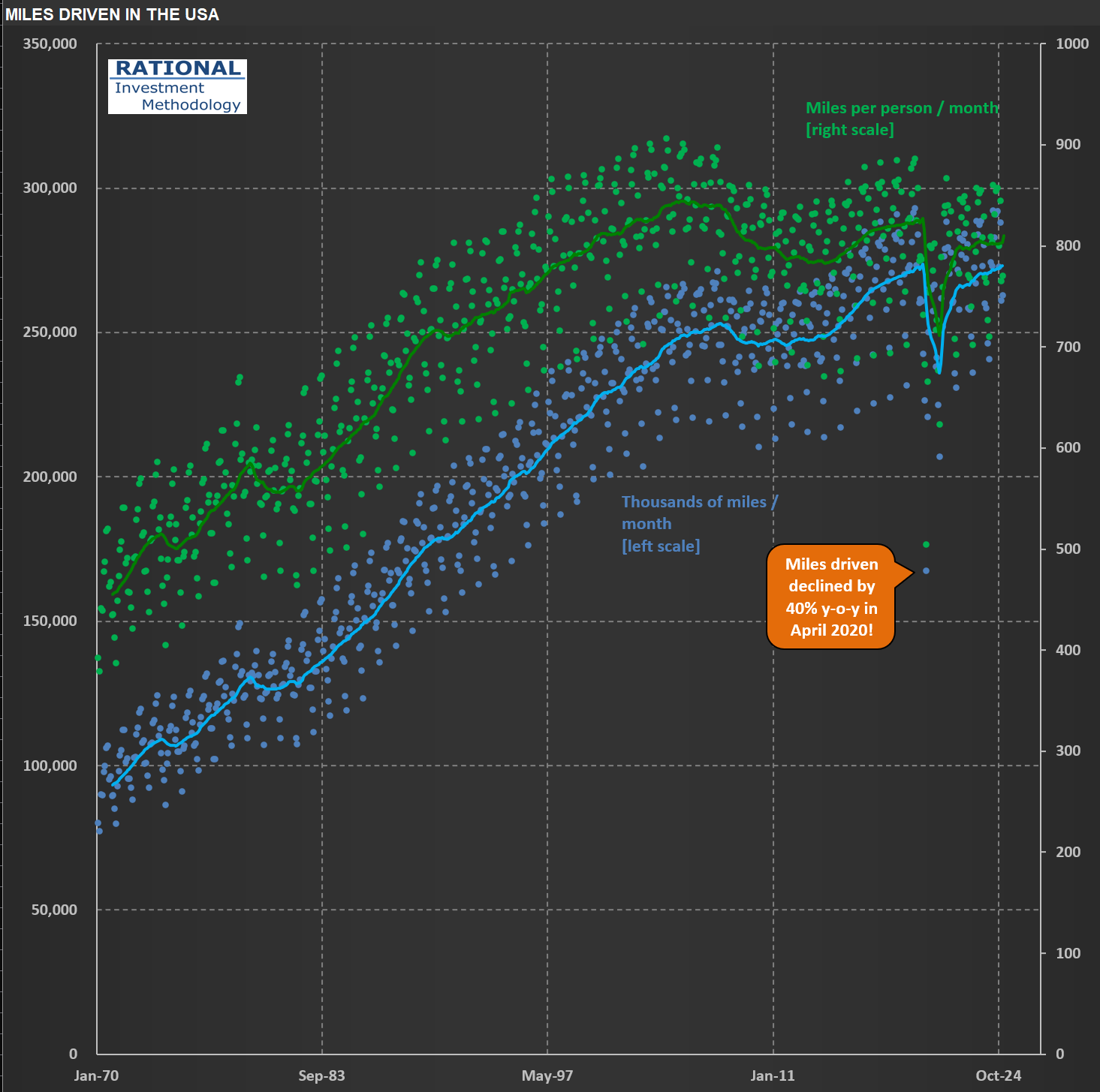

I’m working on $AAP (Advance Auto Parts) today, one of the top three auto parts retailers - more on the business later. Now I’m sharing two charts I have in my analysis to ensure I’m aware of some secular trends affecting the industry.

The first shows total miles driven (in blue) and miles driven per person (in green). The lines are a trailing 12-month figure. Total miles driven still grows, but not by much. It is interesting to note, however, that miles driven per person peaked in 2005—two decades ago!

If people drive less, they should be buying fewer cars—at least per capita, right? We observe this in the data—see the second chart. The blue dots show cars sold per month. In red, an index of how many cars were bought per capita is shown. The peak of car purchases in the US happened in the summer of 1979! The last peak of absolute numbers of vehicles sold in 12 months happened 25 years ago, in the summer of 2000.

These figures help me calibrate the underlying potential auto parts sales. On top of the drivers I just shared, I still need to consider how long cars last nowadays. For example, if one observes that we have an “aging fleet” in the US and concludes that they are going to need more auto parts, that might not be the case if cars just last longer. Technology has made parts more durable. Hence you have to consider a cascade of effects when trying to understand what will impact sales in the long run.