A 1990s Redux? Comparing Walmart’s Current Valuation to the Tech Bubble

A recent article in the Wall Street Journal highlighted concerns regarding the potential overvaluation of Walmart. The article can be accessed here. The author primarily focuses on the forward price-to-earnings ratio, contrasting Walmart’s metrics with those of various technology firms, a clever comparison intended to suggest that there may be an issue with WMT’s stock valuation. Are Walmart’s shares overpriced? Indeed, they are; however, at RIM, given the thoroughness and sophistication of our proprietary models, we rely on more than just multiples, which serve as a simplified valuation reference.

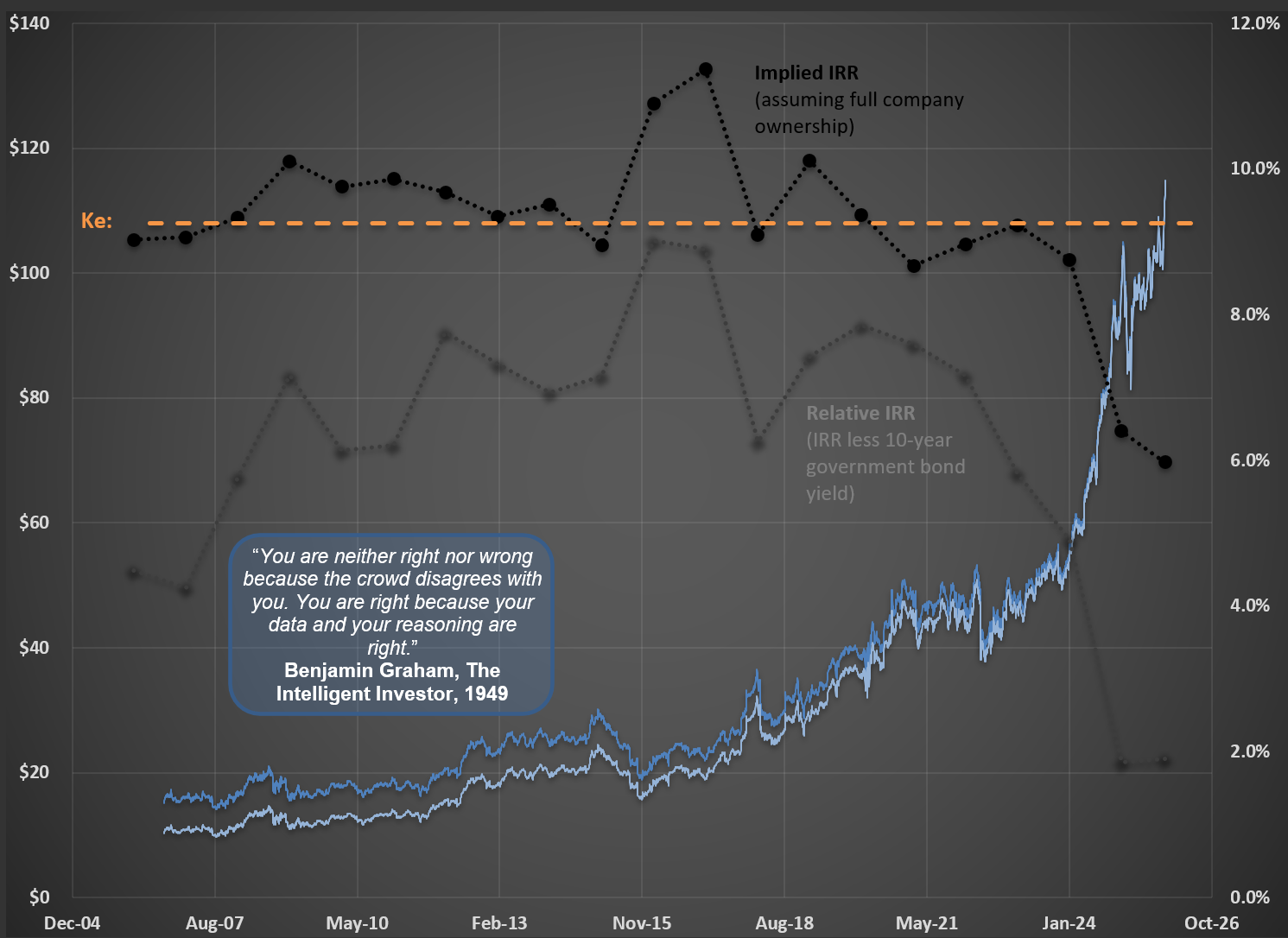

What should be of primary interest to investors is the Internal Rate of Return (IRR) that an investment can generate. Naturally, purchasing an asset at a low price and selling it at a higher price without fully understanding the underlying value may yield a high IRR, but this is not investing—it is merely a fortunate chance. True investing requires acquiring assets only when one believes the underlying business can deliver a historically high IRR, assuming reasonable operational performance.

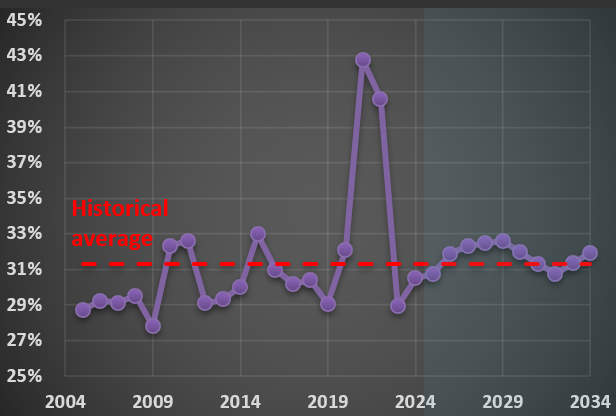

I dedicate extensive time to researching and modelling companies because I aim to invest in businesses where the implied IRR is substantial—approximately 15% annual gains if one were to acquire the entire business, based solely on genuine cash flow to the owner. Where does Walmart stand on this measure today? The first chart provides the answer: Walmart currently offers an IRR close to 6%, the lowest at any fiscal year-end in the past twenty years (indicated by the dark-dotted line). Historically, Walmart shareholders have enjoyed an implied IRR of around 9.2%. This 3.2% difference significantly impacts cumulative returns over time (the calculations are detailed in this post).

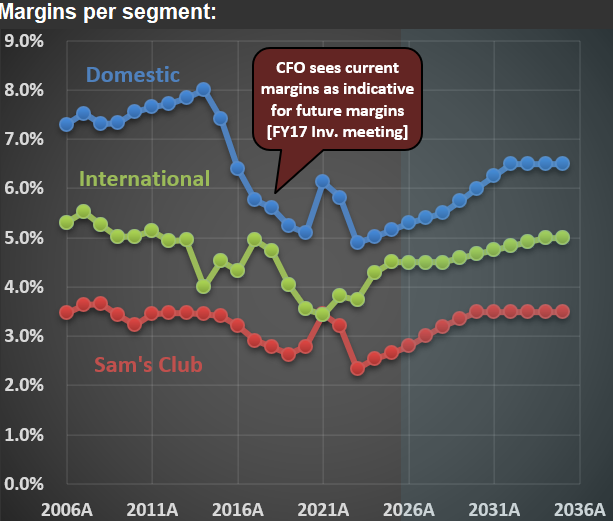

The implied IRRs presented above are derived from RIM’s base-case scenario, which assumes Walmart will improve its margins going forward. The second chart illustrates Walmart’s margins across various segments. It is noteworthy that Walmart’s CFO discussed the prospect of higher margins (approximately 6%) for its domestic business as early as 2017. Except for a few pandemic years, the company has not consistently achieved such margins. Thus, assuming margins increase to levels not regularly seen in over a decade is quite optimistic.

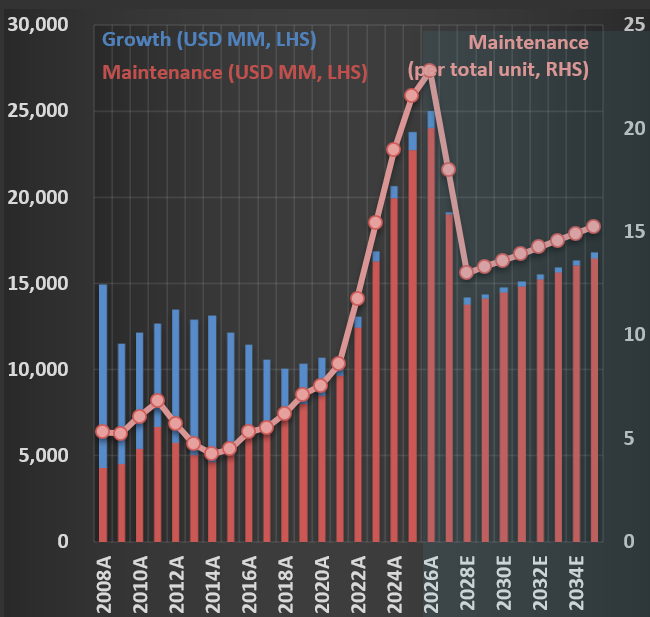

Equally critical to IRRs is the amount of capital expenditure required to attain these margins. The final chart displays Walmart’s capital expenditures over the past two decades and projections for the next ten years. The recent surge in investments is substantial, implying that, all else being equal, higher investment levels reduce cash available to shareholders.

When considering all factors—share price, margins, growth (which has been limited for a mature business like Walmart), and investments—the implied IRR for Walmart stands at a modest 6%. Some may argue that valuations are irrelevant; however, I disagree. As demonstrated in this post, during the 1990s tech bubble, Walmart shares—and a few others—were highly valued. Shareholders who disregarded these elevated valuations at that time experienced poor returns, a scenario that is quite plausible for current Walmart investors purchasing at today’s prices.

$FLS Share Price Surge: Nuclear Hype Meets AI Mania

This past week, $FLS (Flowserve Corporation) released earnings that clearly illustrate how the AI race and associated mania can spill over into even traditional companies, particularly in the industrial sector. Flowserve is a classic industrial company that sells technical equipment to its corporate clients. It specializes in precision-engineered equipment that manages the movement, control, and protection of industrial fluids and gases in critical infrastructure applications. The company operates through two primary business segments: the Flowserve Pumps Division (FPD), which focuses on highly custom-engineered pumps, and the Flow Control Division (FCD), which designs, manufactures, and services industrial valves.

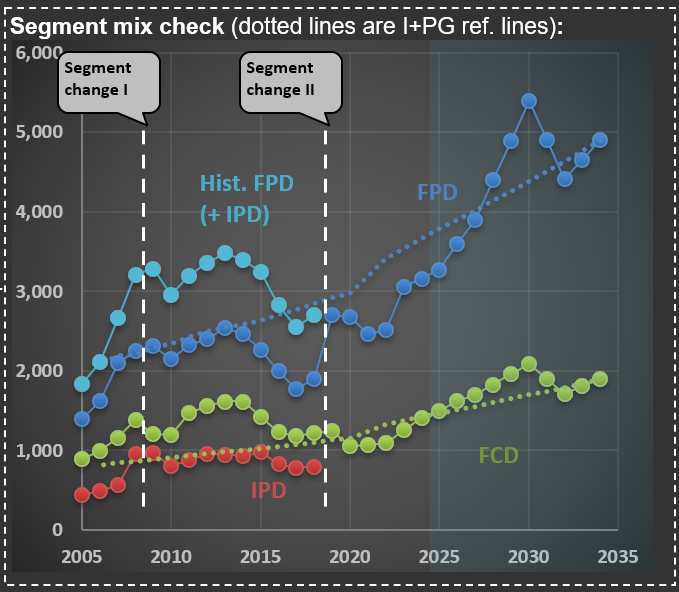

The first chart shows sales over the two main segments. But you can also see a line that ends abruptly—that is their IPD (Industrial Products Segment; the red dotted line in the chart), which was merged into FPD. It isn’t uncommon for companies to change segments—Flowserve did so twice in the past 20 years. I find it challenging when this happens, as it makes it harder to track the progression of sales and margins over the years.

A case in point is what happened when they released their earnings for 3Q 2025. Shares jumped more than 30%. This is more than three times what was observed during earnings releases when the company surprised the market positively over the past decade. The reason: the focus on nuclear energy. At the end of the post, you see the cover of their earnings release presentation—that is a nuclear power plant.

The word “nuclear” was mentioned 25 times in its earnings presentation and 59 times during the conference call transcript. And the market was excited with phrases like “we believe that nuclear flow control opportunity set could be $10-billion-plus over the next decade,” pushing share prices up abnormally. Now, do you know how much nuclear-related sales Flowserve has? They sold $160 million in pumps and valves in 2024, somewhat related to nuclear facilities. This is 3.5% of their sales (of $4.6 billion). So, do you think that a company that isn’t relevant in the nuclear space should increase in value by more than 30% because they mentioned the word “nuclear” in their earnings release?

Because of AI’s high electricity consumption, there is widespread speculation that countries like the US will reignite their nuclear power programs. First, a long-term renewed interest in nuclear energy is already a speculative assumption. Second, nuclear facilities construction takes years (usually measured in decades) to complete. And even if it does happen, the chances of Flowserve meaningfully participating are small.

The mere mention of a word in a release leading to significant share price appreciation reminds me of 1999, when companies were adding “.com” to their names and instantly increasing in value. What happened with Flowserve might be something similar. A company that only tangentially touches the nuclear space increased its valuation by disproportionately associating itself with this field. This is what a mania looks like.

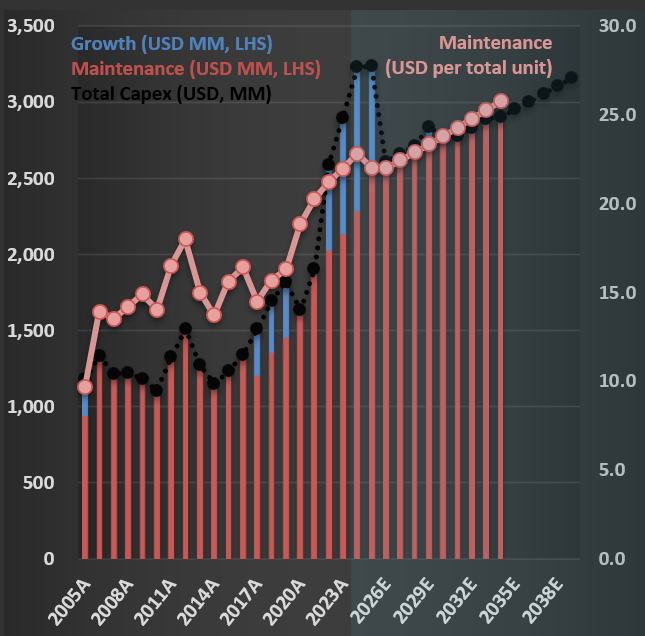

Government Spending and Mortgage Rates: Understanding the Connection That Matters

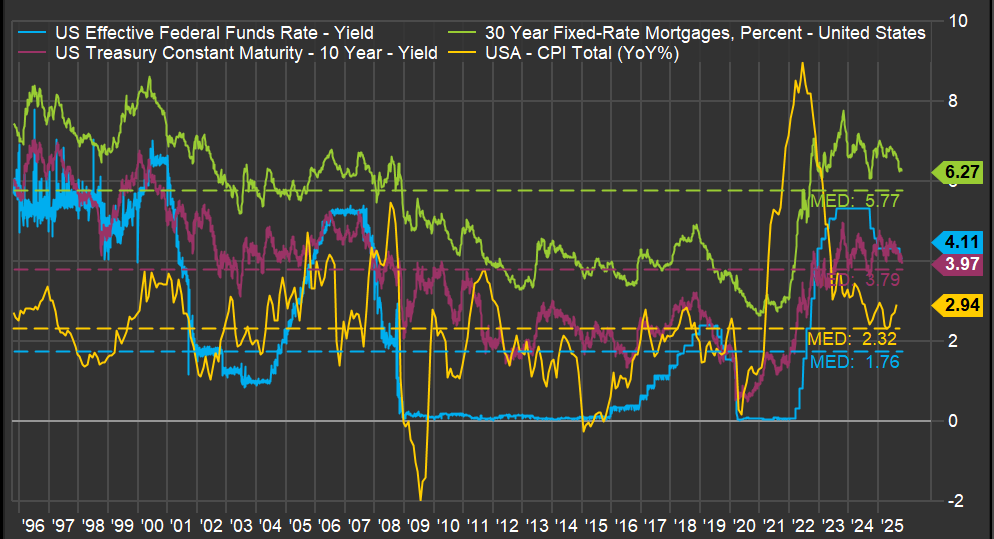

One of the key variables for the housing market is the 30-year mortgage rate. It isn’t uncommon to see posts on social media about the movement of such a rate in a single day. However, rates like this need to be viewed over a much longer timeframe. Below is a chart showing key series over three decades. In green is the 30-year mortgage rate. Note how it maintains a particular spread from the 10-year Treasury note (in magenta). Also interesting is the blue line—the Fed Funds Rate—which shows a more step-like pattern as the Federal Reserve uses it to achieve its dual mandate of inflation control and employment.

But the most critical line is the yellow one: inflation. A spike in inflation drove the jump in the 30-year mortgage rate, which had a profound impact on the existing home sales market, as I discussed in a previous post (here). But what caused such a sudden spike in inflation? The ferocious money-printing during the pandemic years.

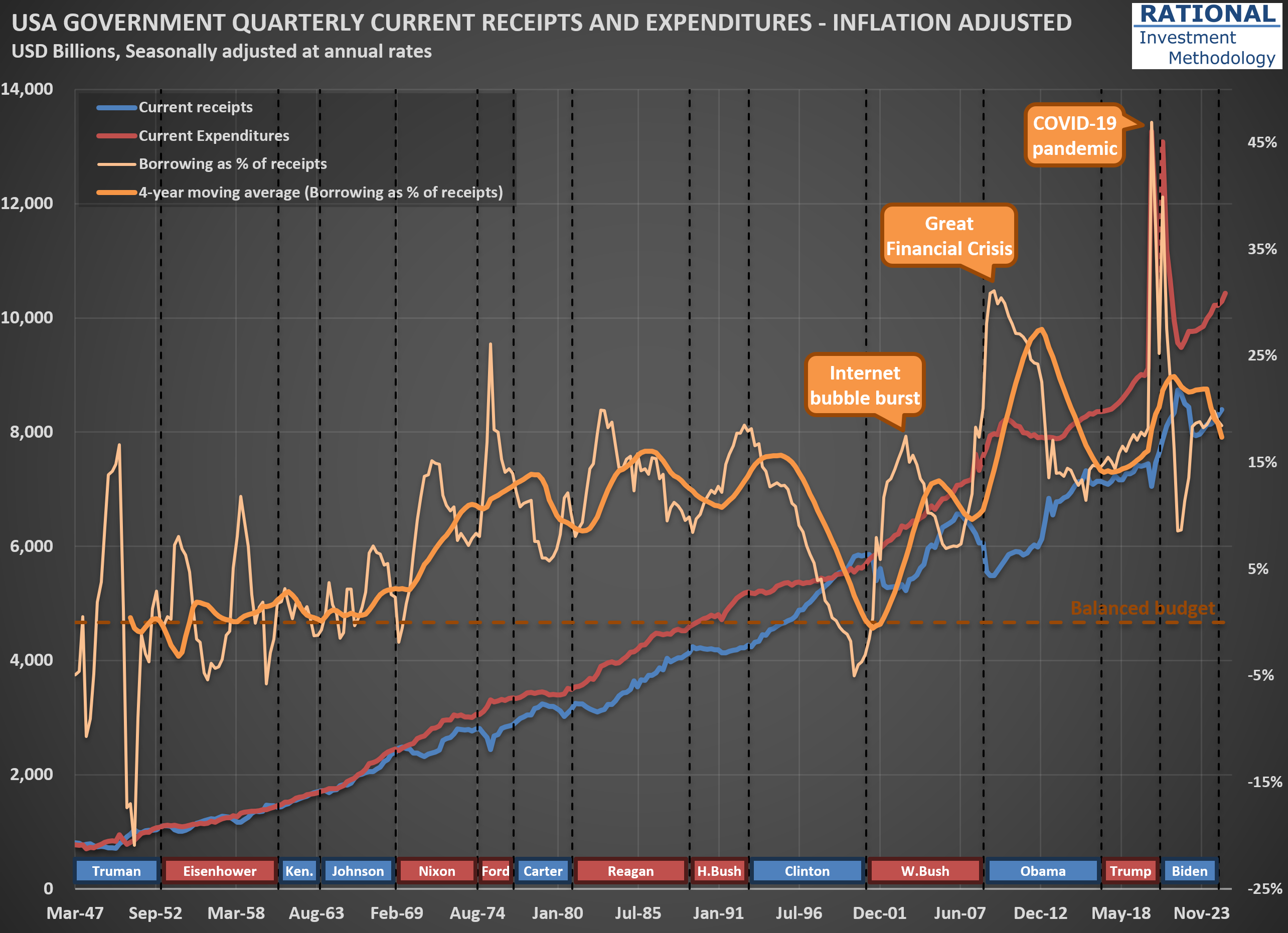

The question one needs to answer regarding the 30-year mortgage rate isn’t what it will do today, or even next year. The driver of all the lines you see in the first chart is how much the US government continues spending above its tax receipts. And the trend isn’t encouraging. The second chart shows (in orange) how much the US government has borrowed to cover its expenses, which include all transfers—think Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid. Note how spending increases with each crisis, with a massive 47% ratio (meaning the government spent 47% above its income) during the acute phase of the COVID-19 pandemic.

What is particularly concerning is that, apart from the late years of the Clinton administration when receipts increased substantially due to the internet bubble, the US has largely ignored fiscal discipline since the 1970s. One might argue, “Well, the US can do it because its currency is the global reserve.” However, no government in history has managed to abuse the monetary system indefinitely. The question is not “if” but “when” we will see stress on government bond yields. When that happens, the housing market will suffer significantly, and we will likely embark on another recession led by the housing market—which, as I’ve shown, has been part of many US economic crises (see here).

So what should an investor do? Focus on companies that, over decades, have navigated crises and emerged fully operational on the other side. Not necessarily unscathed—it is common for a company’s earnings to suffer during a recession—but healthy enough to continue business as usual after the storm passes. That is what I work on every day (for the past 20 years), spending countless hours running company-specific analyses. It isn’t fun or easy, but it is necessary.

When “Hedges” Hurt: Lessons from $GLD and $SLV Cycles

Clients, friends, and anyone who knows I work with investments often ask for a view on the price of gold. The answer is consistent: not much, because gold prices sit outside my circle of competence. To have a view on any commodity, it is essential to know who the suppliers are, how much they can produce, and at what cost—in other words, to build a cost curve for the commodity in question. Without that information, any allocation to such a commodity could be too speculative, even if the true intention is to provide a hedge against inflation or as a diversification within a broader portfolio.

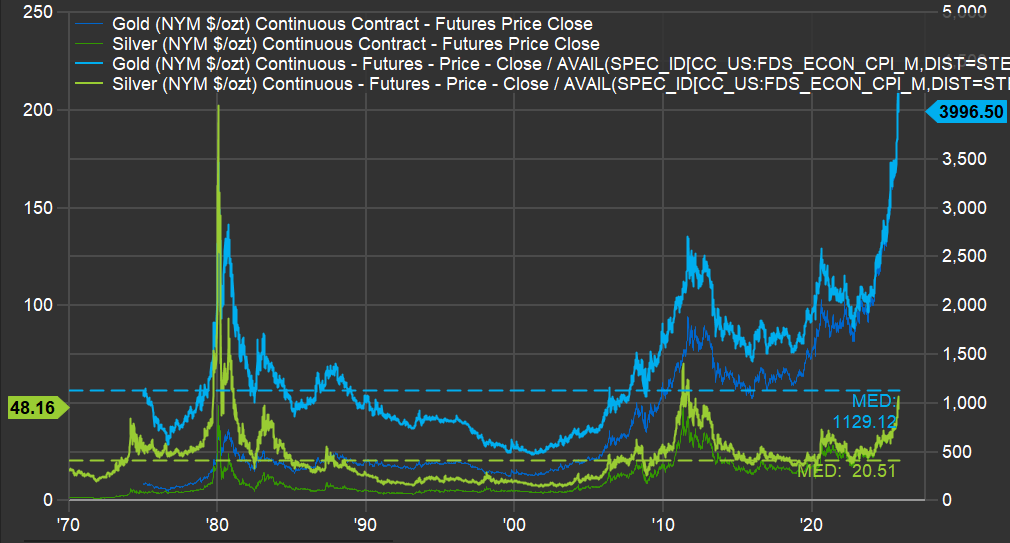

However, a long-term perspective on how gold prices (and their often-mentioned companion, silver) behaved—particularly during the U.S. inflation run-up in the 1970s and 1980s—can still be useful; look at the chart, which shows gold (dark blue), gold adjusted for inflation (light blue), silver (dark green), and silver adjusted for inflation (light green).

First, on gold: when inflation was rampant in the late 1970s, gold, in today’s dollars, reached roughly $2,800 per ounce; today’s level sits about 43% above that prior peak. However, that peak was 45 years ago, implying a real return close to 1% per year since then. What followed should give current gold holders pause: prices declined for roughly 20 years, reaching around $500 per ounce in the early 2000s—an 82% drawdown, leaving about 18% of the original investment two decades later.

Silver is even more extreme. It is around $50 per ounce today, after having surpassed $200 per ounce (in today’s dollars) in 1980; by the 2000s, it traded near $8 per ounce—a roughly 96% decline from that earlier level. Imagine looking at an “inflation hedge” bucket and finding only 4% of it remained.

That’s as far as this analysis goes for these two precious metals: invest with care, recognizing that prices can always rise, but extended speculative phases can produce negative returns for decades. In silver’s case, the closest it came to its 1980 record was about $60 per ounce in the early 2010s—still roughly 70% below the peak.

Why $HSY Defies Conventional Forecasting Wisdom

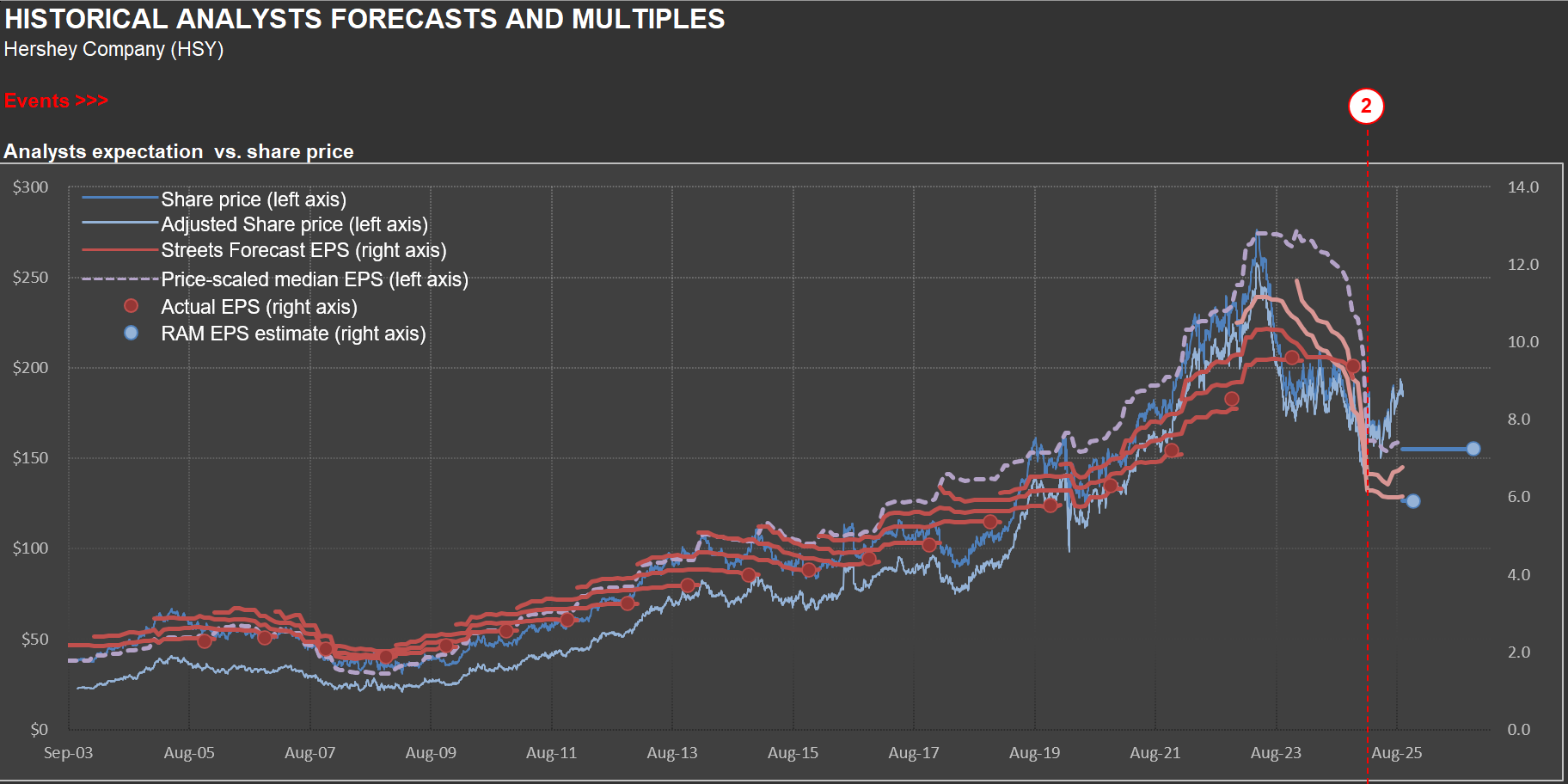

In early 2023, Hershey’s shares were trading near $275—the same vicinity where RIM’s short position kicked off (the position has since been closed). By Q1 2025, they’d slumped below $150, underscoring the perils of overconfidence in a seemingly stable business. Nowhere was this more evident than in 2Q 2024, when Hershey reported its worst quarterly sales decline in twenty years: a steep −16.7%.

Management broke down the drivers of that plunge as follows: ERP-driven inventory cuts (approximately 9 points), retailer timing shifts (approximately 6–7 points), discretionary spending pullback, channel migration, merchandising cuts, and category softness.

Just as sales surprises can upend forecasts for a chocolate maker, cost fluctuations add another layer of uncertainty. In 2Q 2025, Hershey’s adjusted gross margin plunged 510 basis points, driven by cocoa price spikes, elevated manufacturing costs, and tariffs. Those headwinds largely offset price increases, productivity gains, and transformation savings. Looking ahead, management projects full-year gross margin erosion of 675–700 basis points—an eye-watering swing that few analysts anticipated twelve months prior - the chart above shows how fast earnings were revised down (dragging with it HSY’s shares).

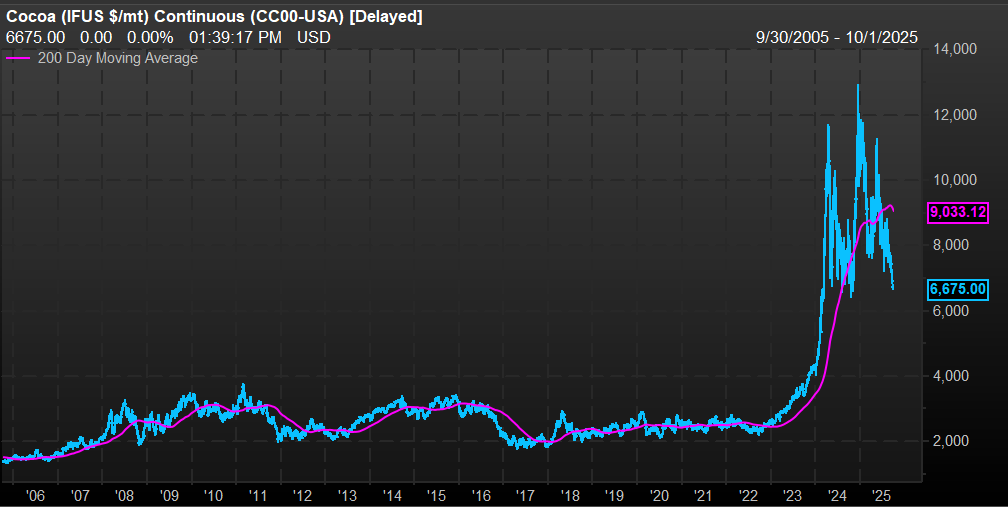

The Hershey’s saga offers a cautionary tale for forecasting any business: even “mundane” companies confront complexity at every turn, exposing how little control companies might have over outcomes. A case in point is the price of cocoa (see the second chart). Prices surpassed $12,000 per metric ton in late 2014, from an average of around $2,500 per metric ton in prior years. Hershey uses derivatives to try to control commodity price volatility, but something of that magnitude, impacting the most important commodity used in their manufacturing process, can’t be neutralized.

If projecting Hershey’s sales and profits—with its nearly century-old brands and predictable seasonality—can trip up analysts, imagine the challenge of forecasting fast-evolving technology ventures. So approach new and uncharted territories carefully.

Forecasting $EXP Sales: How Home Starts and Industry Behavior Intersect

Sometimes clients wonder why I devote so much time to producing (and updating) a wide array of industry-wide analyses. For example, you’ve likely seen the posts I’ve published covering the housing (here) or transportation (here) sectors. The reason is simple: industry dynamics are typically the critical force shaping sales for any individual company.

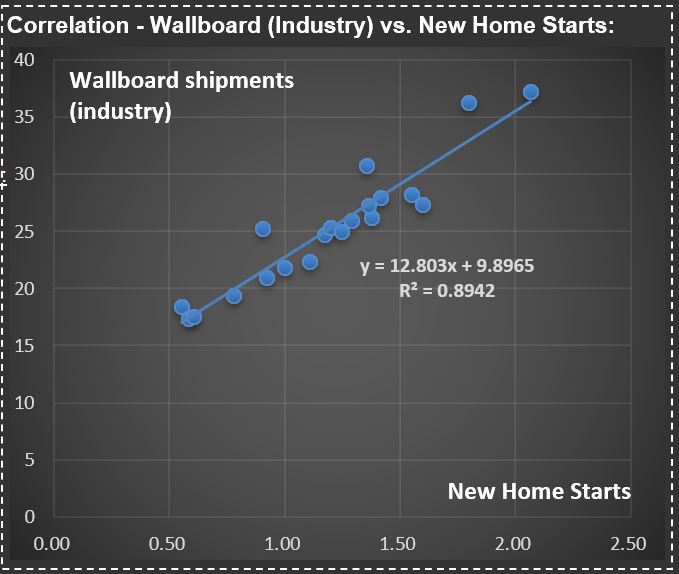

Take today’s focus: $EXP (Eagle Materials), a leading U.S. producer of wallboard and cement, with additional operations in concrete and aggregates. See the first scatter plot.  It highlights the strong correlation between U.S. wallboard sales and new home starts (that is, newly constructed houses). While not all wallboard goes into new housing, this single variable explains nearly 90% of total sales, reflecting the interconnectedness of adjacent areas within the housing complex.

It highlights the strong correlation between U.S. wallboard sales and new home starts (that is, newly constructed houses). While not all wallboard goes into new housing, this single variable explains nearly 90% of total sales, reflecting the interconnectedness of adjacent areas within the housing complex.

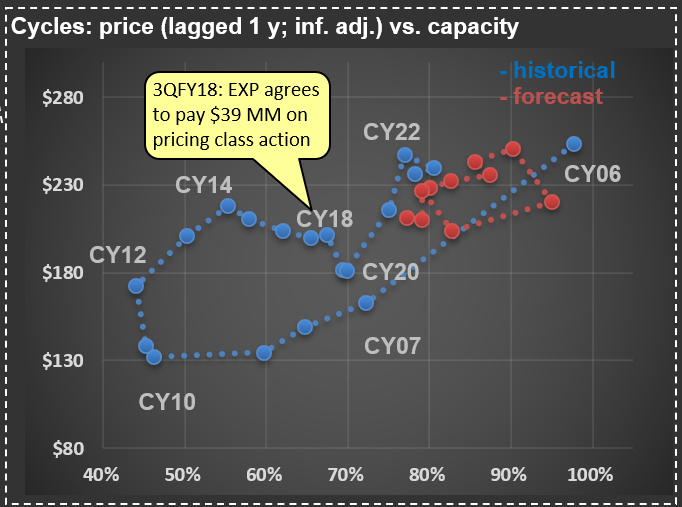

This is why understanding the cycles of new home starts in the U.S. is essential for accurately forecasting sales for Eagle Materials’ wallboard segment. From there, it’s a straightforward process to estimate $EXP’s market share and, with further analysis, explore the dynamics between capacity utilization and wallboard pricing—take a look at the second chart for a visual depiction.

During the mid-2000s housing boom, capacity utilization at $EXP and its competitors reached very high levels (as did the price of wallboard). As the cycle turned and housing starts collapsed, utilization rates dropped—and prices followed. Then, something unusual happened: in the early 2010s, wallboard prices climbed sharply, even though the industry’s fundamentals seemed weak. For a while, my analysis questioned its relevance—until, almost a decade later, Eagle Materials (along with USG, the market leader) was fined tens of millions of dollars in a class action for price-fixing. In short, the major players had been colluding.

Looking ahead, pricing should remain relatively disciplined, especially with fewer homes expected to be built in the coming years (see my recent analysis on U.S. Census Bureau data and future new home starts - here). That said, if significant industry players resume collusive behavior, all bets are off—so I’ll be keeping a close eye on price developments in this segment.

Did $EXPD Miss the Storm? Lessons from Their Q&A

As I updated my work on $EXPD (Expeditors; I discussed the company’s business in a prior post—here), I searched for their latest Q&A documents. Expeditors doesn’t host analyst conference calls, but you can send them questions that management periodically responds to. The most intriguing responses came from their January 13, 2025, Q&A.

What stood out was how a group of logistics specialists didn’t anticipate the tariff storm that was about to hit the industry. Here’s the exchange:

Question: Regarding Trump 2.0, what concerns are you hearing from customers? How are things different this time around? Has your perspective changed on the likelihood of increased tariffs and a possible trade war? And is there an upside with regard to additional complexity being good for Expeditors?

Answer: Our perspective is that shippers now know what to expect from a Trump administration. Tariffs were certainly a very real issue during his first term, when it often seemed that new rules were being issued nearly every day. But the reality is that many of the tariffs implemented during the first Trump administration were continued and, in some cases, tightened under the Biden administration. Historically, complexity has usually been very good for Expeditors. We are experts at helping our customers navigate complex environments.

At the time, they didn’t know that the tariff changes in Trump’s first term would pale in comparison to what followed. It’s a reminder of how unpredictable economic cycles can be—and how companies must adapt swiftly. Below is a chart showing $EXPD’s historical and forecast net margin. 2021 and 2022 stand out as exceptional years; 2025 is projected to align closer to their long-term average. So far, the current tariff complexity hasn’t been “very good” for margins, but it hasn’t derailed the company, either.

From Shorts to Opportunity: Tracking $SBUX's Turnaround Journey

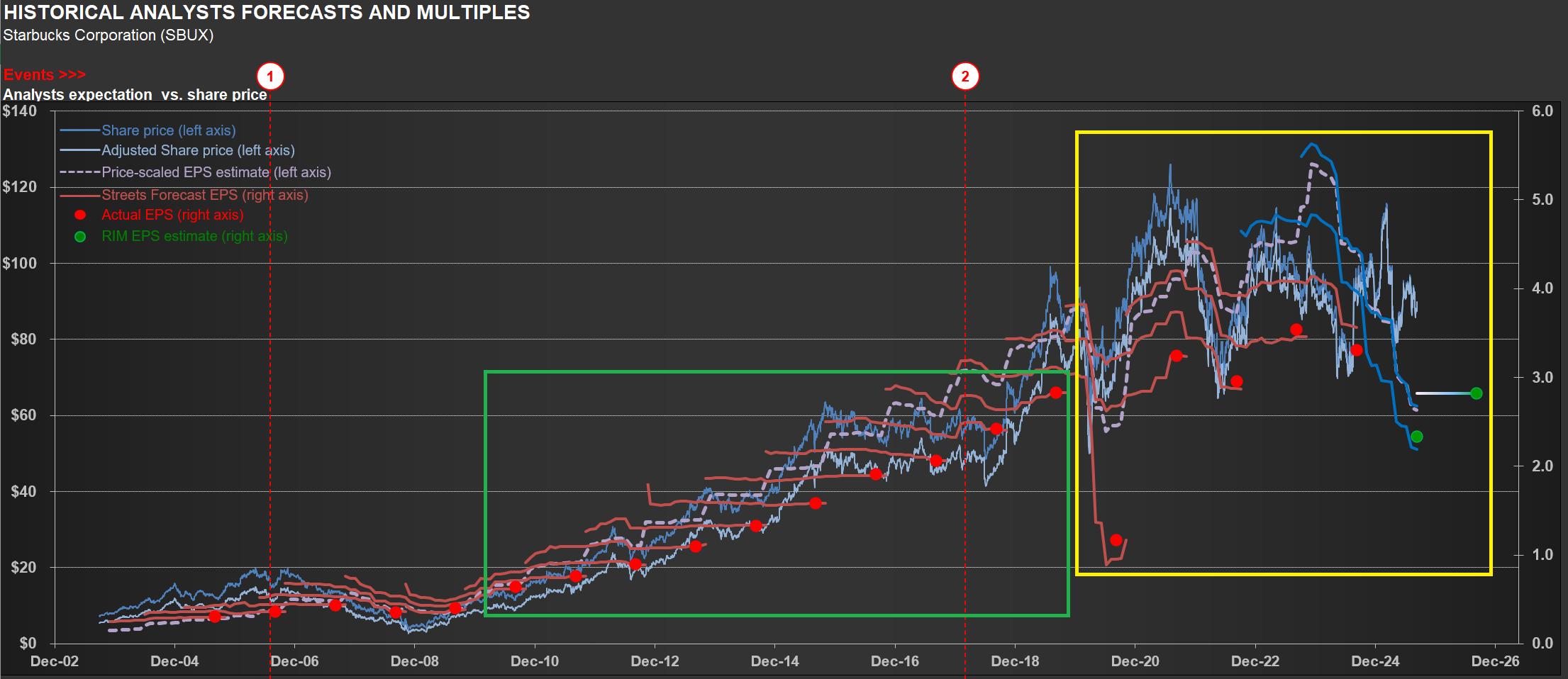

$SBUX (Starbucks) finds itself in a turnaround phase, and management’s language on the latest conference call was telling. They repeatedly described this as the “early stages of our turnaround in the US”—part of a “multiyear effort” to “rebuild” and get “Back to Starbucks.” When executives use words like “rebuild,” it signals they’re addressing fundamental challenges rather than operating from a position of strength.

The company’s financials clearly reflect this reality. Take a look at the chart below—one you’ll recognize from my previous analyses. It tracks the company’s earnings versus share price over time. Notice how earnings estimates have become much more volatile recently (yellow rectangle) compared to the pre-pandemic, post-GFC period (green rectangle). While volatility during the pandemic’s peak was understandable, why the continued decline now?

The EPS drop stems primarily from significant operating margin contraction, driven by deleverage and substantial strategic investments in the “Back to Starbucks” initiative. Management describes this as a comprehensive plan aimed at transforming both the business and its culture—ultimately building a stronger, more resilient, and consistently growing company. Chairman and CEO Brian Niccol calls it “the right plan,” grounded in customer and partner feedback and rooted in the company’s core identity as a welcoming coffeehouse serving fine coffee handcrafted by skilled baristas.

But transformation comes with costs. The effort includes over $0.5 billion in additional labor hours for the Green Apron Service rollout and significant spending on Leadership Experience 2025—an event that brought together 14,000 coffeehouse leaders. Will it work? Time will tell, but we should expect continued volatility in earnings expectations along the way.

Here’s what makes this interesting from an investment perspective: if the turnaround succeeds, this volatility could create opportunities to acquire shares at a substantial margin of safety. The last time I owned $SBUX shares was back in 2009. My last three positions on the name were shorts—all successful trades, but that’s the past.

The key question now is whether management can execute on its vision while navigating the inevitable bumps ahead.

Census Bureau’s 2023 Data Points to Weaker Household Growth—A Closer Look

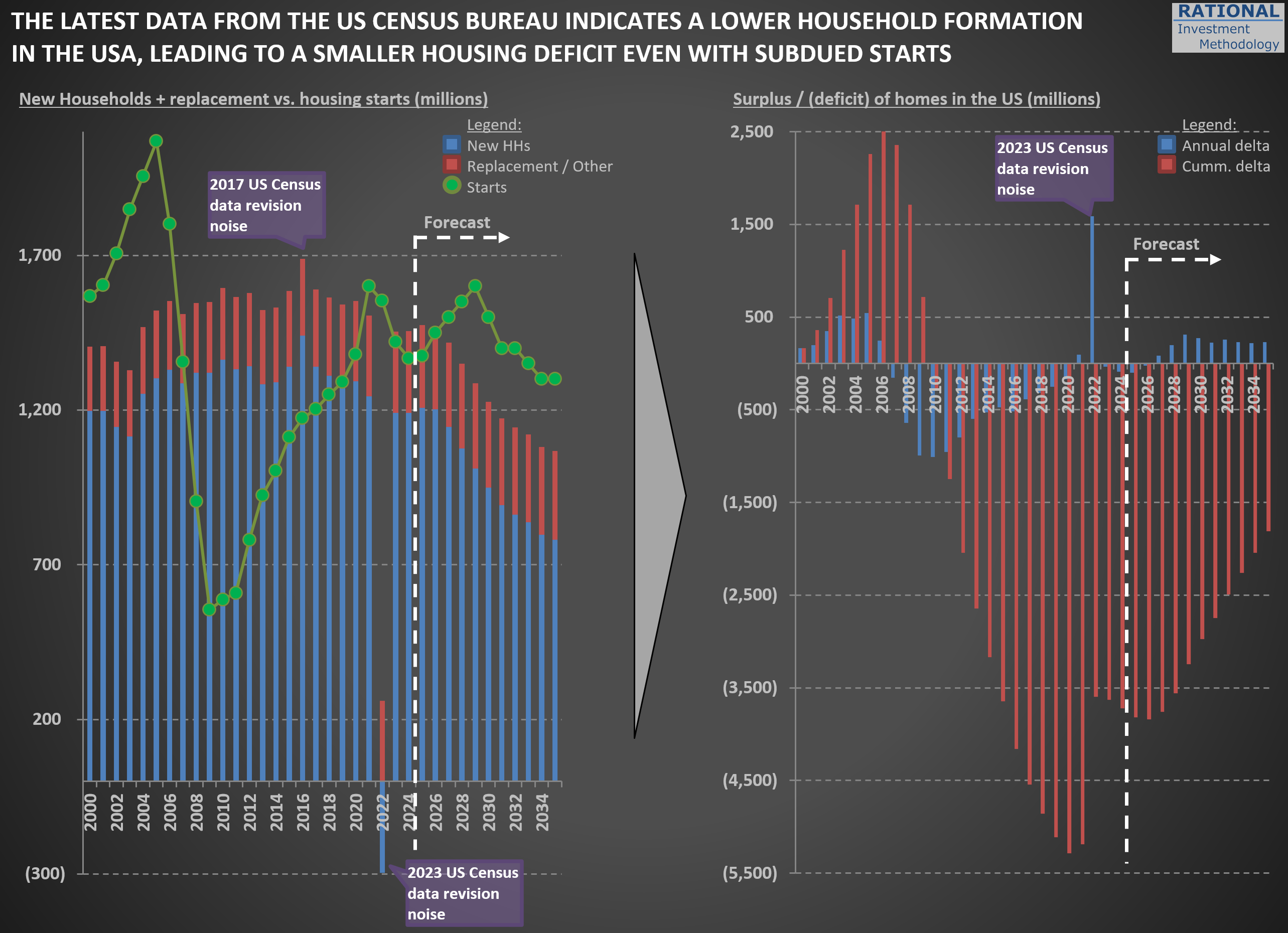

I’ve incorporated the US Census Bureau’s 2023 National Population Projections (you can explore the full dataset here) into my estimates of new household formation in the US. Typically, these revisions are minor—but not this time. Back in February, I highlighted the shrinking cohort of young families when discussing challenges for Carter’s ($CRI) in this post. The new projections, however, point to a broader slowdown in household formation.

The chart below reflects these updates. First, you’ll notice a spike in “noise” around the 2022 figures (and a much smaller one in 2016). Although the data was published in 2023, the Census Bureau sometimes revises prior-year numbers—and I always use the most recent figures available, even for past years.

The key takeaway is that new household formation will grow much more slowly than it has over the past 25 years. That suggests future New Home Starts (green dots) may be lower than in recent decades. Even with subdued starts, any lingering home‐building deficit from the Global Financial Crisis will shrink significantly—so there won’t be a significant unmet demand waiting to be filled.

In my models, I’ve adjusted the normalized New Home Starts assumption from 1.5 million per year to 1.3 million per year. That change implies slightly lower long-term sales for housing‐related materials. While the valuation impact is modest—given how gradually this trend unfolds—it’s crucial to incorporate these shifting demographics when projecting decades‐ahead performance. I will also eagerly wait for data revisions given recent changes in immigration dynamics, as scenarios the US Census Bureau calls “low immigration” and “zero immigration” might become the new reality.

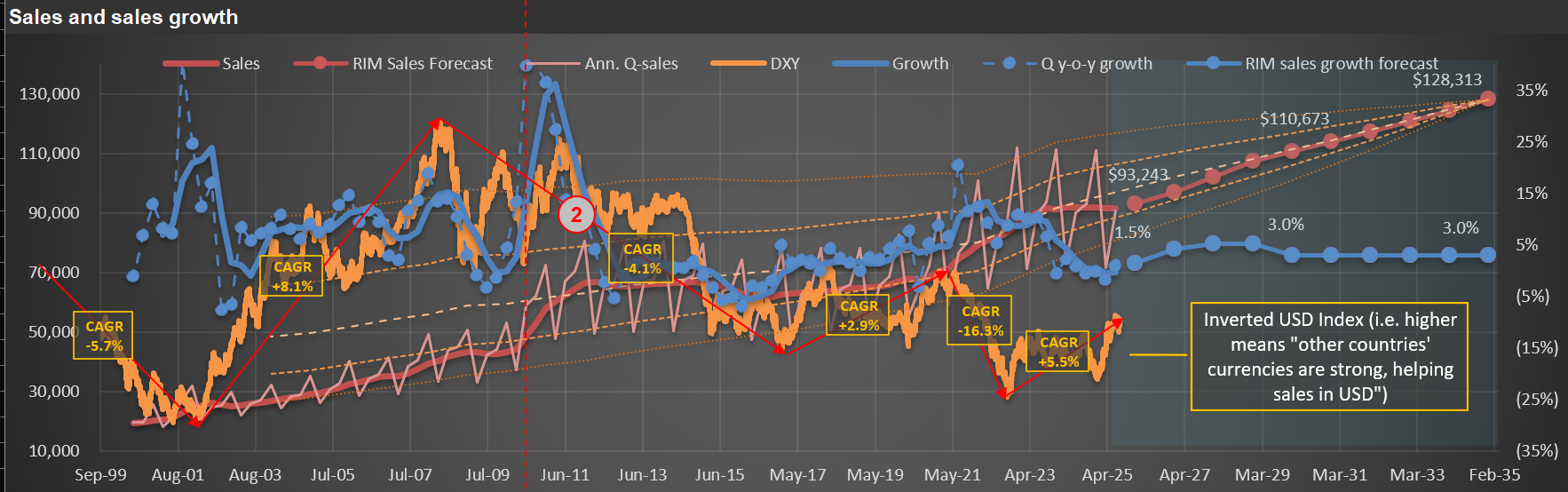

Seeing Through Currency Noise: Interpreting $PEP Sales Trends

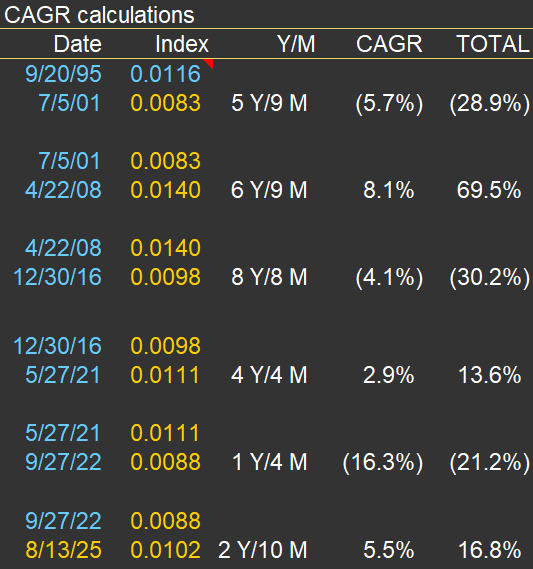

In many of my sales charts for companies with significant international exposure, I include a “USD index”—like the orange line on the chart below. In this case, the chart is for $PEP (PepsiCo). The annotations and text box on the chart highlight periods of substantial change in the USD’s value versus a currency basket (I use the DXY, which includes the EUR, JPY, GBP, CAD, SEK, and CHF). The accompanying table below the chart details the specific dates and quantifies the total and annual appreciation or declines during each cycle.

The index is “inverted,” so it moves higher as foreign currencies strengthen against the USD. It means that when the orange line rises, companies like Pepsi—which report sales in USD—get a boost from currency translation on their international sales. Conversely, when the line declines, it acts as a headwind for reported international sales.

I don’t use this chart to make predictions. Instead, it’s a tool for context. If international sales, reported in USD, look strong, it’s worth checking whether this is due to real underlying growth or simply a weaker dollar. That was certainly the case in the early 2000s. But since mid-2008, the USD has strengthened considerably against other major currencies, so international sales growth, in USD terms, has slowed or even reversed.

Last, there’s been plenty of commentary in 2025 about the “unprecedented” weakness of the USD. While there’s some truth to that, the DXY index is not far from its late-2016 peak—and, in fact, the USD only reached a higher high (represented by a lower point for the orange line) in 2022.

The takeaway? It’s essential to maintain a long-term perspective on FX rates. As the table below demonstrates, cycles of appreciation and depreciation can persist for many years (see the years and months for each cycle listed in the table).

$MLKN and the “AI Arms Race”: Why Tech Spend and Furniture Sales No Longer Move Together

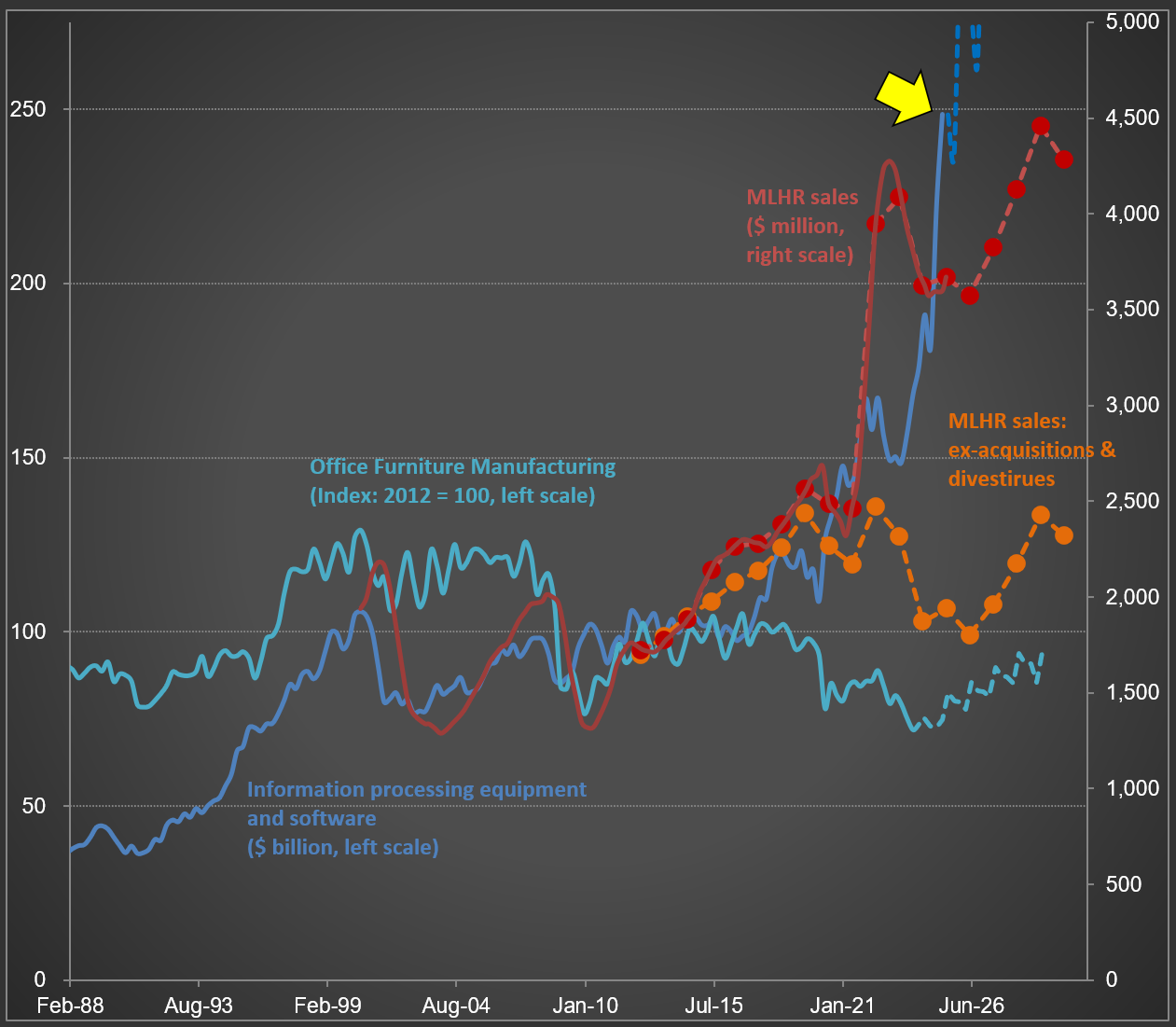

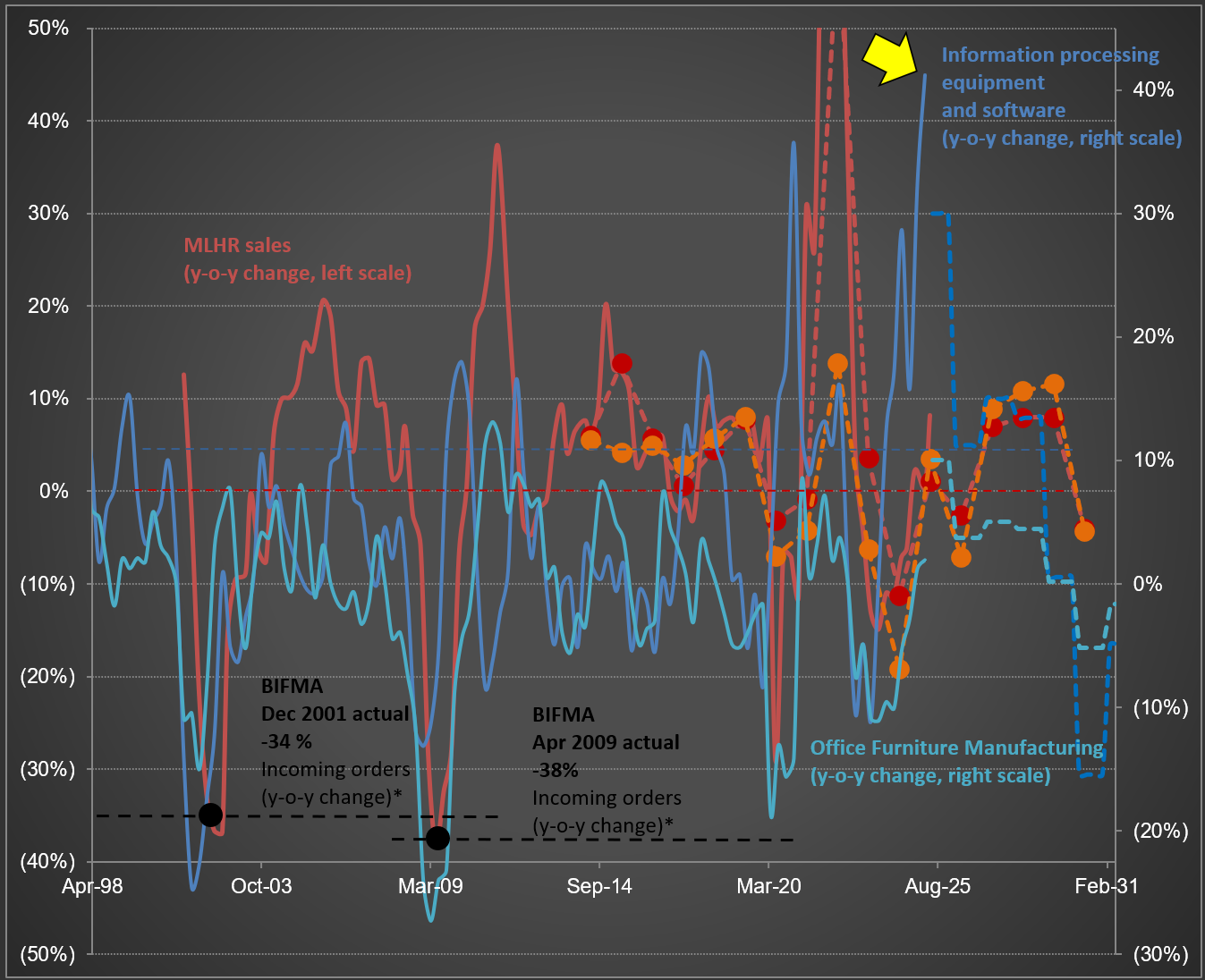

While updating my analysis for $MLKN (MillerKnoll; the largest office furniture company in the Western hemisphere), I was struck by the sharp rise in Information Processing Equipment and Software spending (dark blue line)—take a look at the first chart below. The most recent datapoint, highlighted by the yellow arrow, shows annualized sales reaching $250 billion.

The second chart, which tracks year-over-year changes, illustrates why I’ve included not only MillerKnoll’s sales but also two broader industry data series (including Office Furniture Manufacturing). Notice how the volatility in the blue lines closely mirrors the swings in MillerKnoll sales (in red), and even lines up with significant industry downturns reported by BIFMA (the Business and Institutional Furniture Manufacturers Association) in both 2001 and 2009.

Perhaps someday, Information Processing Equipment and Software spending will once again move in step with office furniture sales. For now, though, it seems primarily driven by today’s “AI arms race.” The latest year-over-year increase surpassed 41%—the highest on record for this data series. It’s also striking that if you adjust for inflation, this series remained at a similar level from the post-Internet 1.0 bust in 2002 up until early 2020. The dramatic surge started only after that point. It will be interesting to see in the coming years how sustainable (or not) this pace really is.

Why “Simple” Numbers Lie: Lessons from $FDX and the Art of Financial Analysis

Why do I devote so much effort to detailed financial analysis of the companies in RIM’s CofC(*)? It’s because companies are constantly evolving, and off-the-shelf calculations like “sales growth” or “margin trends” frequently become meaningless in the real world.

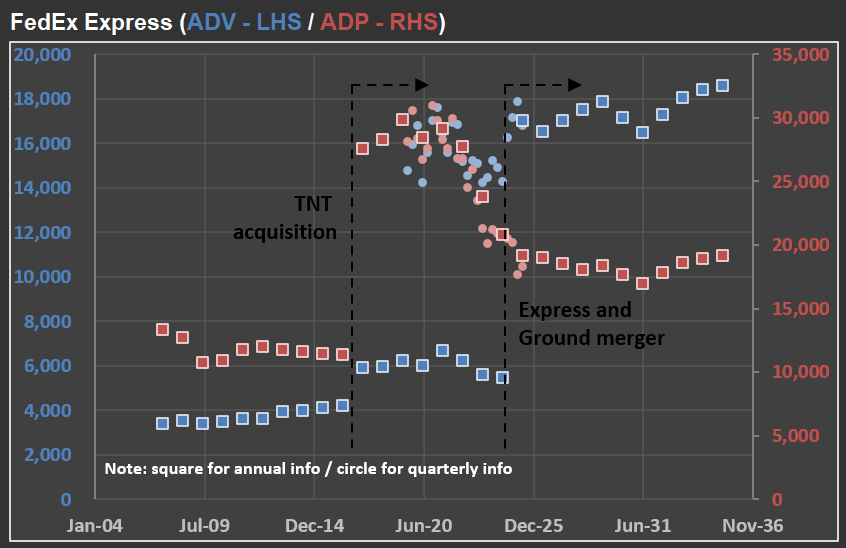

Take $FDX (FedEx) as an example. In the picture below, you’ll see how FedEx has reported ADV (Average Daily Volume) and ADP (Average Daily Packages) for their Express segment over the last 20 years, along with “base case scenario” forecasts for the coming decade.

First, notice the significant jump in ADP in 2017. That spike came right after the acquisition of TNT Express—a major European operator. The timing, however, was unfortunate: only months later, FedEx was hit by the NotPetya ransomware attack, which severely impacted TNT’s IT systems. Nearly every hub, facility, and depot had to have its systems rebuilt from scratch. The recovery was extensive, and FedEx estimated immediate losses of at least $300 million due to reduced shipping volumes, lost revenue, and higher remediation costs.

Fast-forward to recent years, and the numbers became complicated again. FedEx has merged its Ground and Express segments, moving closer to the model used by UPS (which already operates a unified network) and adjusting to changing parcel volumes after the ecommerce surge. Although no new company was acquired this time, the way FedEx reports its numbers has changed—once again making direct year-over-year comparisons challenging.

That’s why I continuously adapt my valuation models to account for these reporting changes. If I don’t understand exactly what changed (and when), the risk of producing misleading forecasts rises dramatically. Back to the model…

(*) CofC = Circle of Competence

The Manufacturing Construction Surge: Signal or Noise for $FAST?

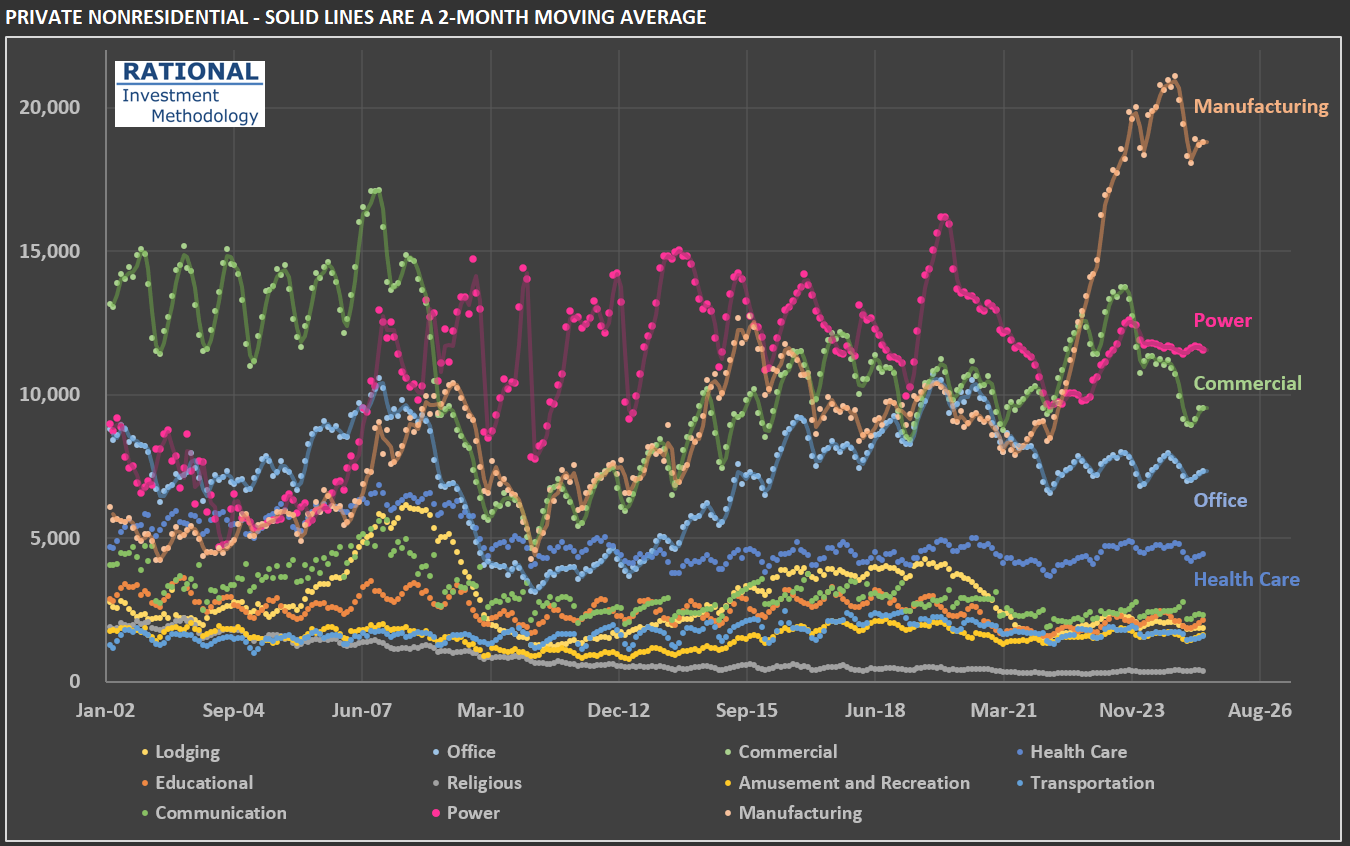

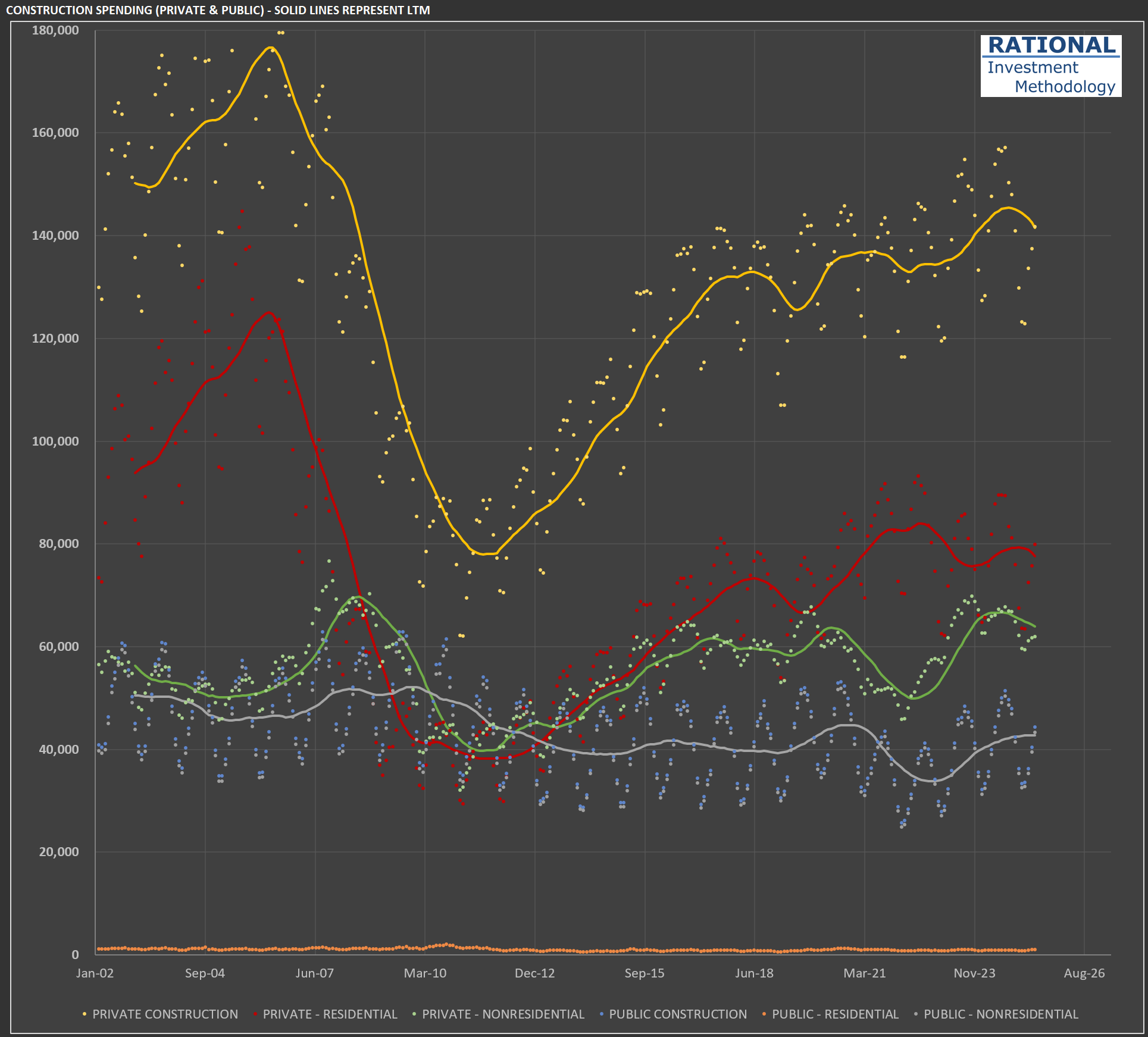

As I work on my analysis of $FAST (Fastenal)—a major industrial and construction supply distributor specializing in fasteners and related maintenance, repair, and operations (MRO) products—I’ve decided to update my analysis tracking construction spending in the USA. After all, the more activity there is in this sector, the more demand Fastenal might see for its products.

The data, from the US Census Bureau, begins in the early 2000s. The first chart below shows subcategories of a broader category: private non-residential construction. I’m highlighting this first because it reveals the abnormal increase in manufacturing-related construction. Manufacturing spending, measured in millions of dollars per month, doubled from around $10 billion to almost $20 billion per month in just a couple of years[*]. The increase starts in 2022 for a clear reason: the CHIPS and Science Act, the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), and the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA) provided substantial federal subsidies, tax credits, and direct funding specifically aimed at boosting domestic manufacturing, particularly in sectors such as semiconductors and clean energy technologies.

However, it’s essential to put this increase in a broader context, hence the second chart. The green line represents the sum of all private non-residential investments, totaling more than $60 billion per month—a level it has maintained since recovering from the significant decline during the GFC[**]. Notice, however, that private residential construction (in red) is the most prominent subcategory in this chart, with almost $80 billion in monthly spending. When you combine both private-residential and private-nonresidential, you get more than $140 billion in monthly construction spending. The other lines refer to public construction, which is dominated by nonresidential projects (such as highways, sewage, and water treatment). However, this represents a relatively minor component of construction spending, totaling approximately $40 billion per month.

So, is a $10 billion increase in manufacturing-related construction significant? When you combine both private and public spending (totaling around $185 billion), it represents slightly more than 5% of the total. It’s not nothing, but it shouldn’t be the reason for someone to expect a massive increase in construction activity nationwide. The government might intervene even further with additional subsidies. However, the country’s level of debt and current twin deficit should make it more challenging to do so. But we live in times where fiscal restraint appears irrelevant to governments, so time will tell how much more abnormal activity we’ll see in this subsegment of the construction space.

[*] All figures in this chart are adjusted for inflation and population growth [**] Global Financial Crisis

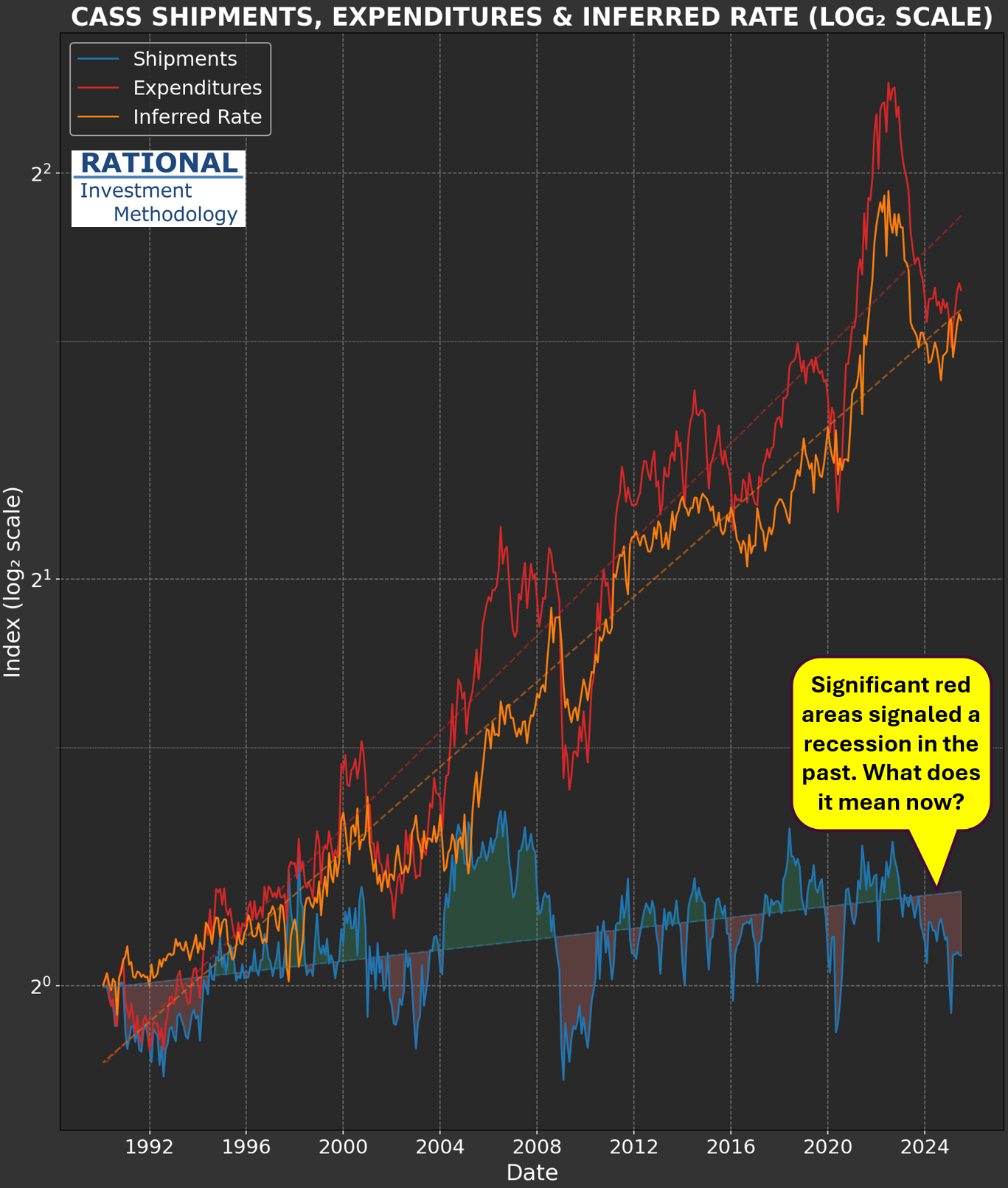

The Cass Transportation Index: Interpreting the New Wave of Red

A few months ago, I introduced you to the Cass Transportation Index. If you’d like a refresher on the various time series Cass releases, you can revisit my earlier post here.

Today, I’m turning the spotlight to the shipments series—take a look at the chart below. The line in blue tracks shipments and has now logged its 29th consecutive negative year-over-year print. For this update, I opted to display the series as-is (in my previous chart, I had multiplied it by three) to emphasize the significant inflation we’ve seen in U.S. transportation services. Simply put, shipment volumes have increased far less than costs (as illustrated by the red line). The primary factor here is the sharp rise in the “inferred rate,” which reflects the actual price that shippers are paying to move goods.

You’ll also notice on the blue series: whenever the data runs above the trendline, the gap turns green. When it dips below, the area is filled with red. Historically, when the red area became substantial, it coincided with recession—think early 1990s, late 2000s, and the coronavirus pandemic period. Conversely, a dominant green area marked periods of above-trend economic activity, most notably in the early/mid-2000s during the first housing bubble.

So, what should we make of the fact that the red area is now so pronounced? Is this recession territory? If so, why don’t GDP figures show a slowdown? At first, you could argue it’s the economy “working off” the excesses of the pandemic. But this red patch is already much larger than the green area seen when government stimulus was being poured out. Even if we start to see a recovery in transportation volumes, the size of the red area will continue to grow for some time yet.

As earnings season gets underway, I’ll be watching closely for commentary from companies regarding overall activity levels. I sense that few will sound especially optimistic about the landscape in their sector.

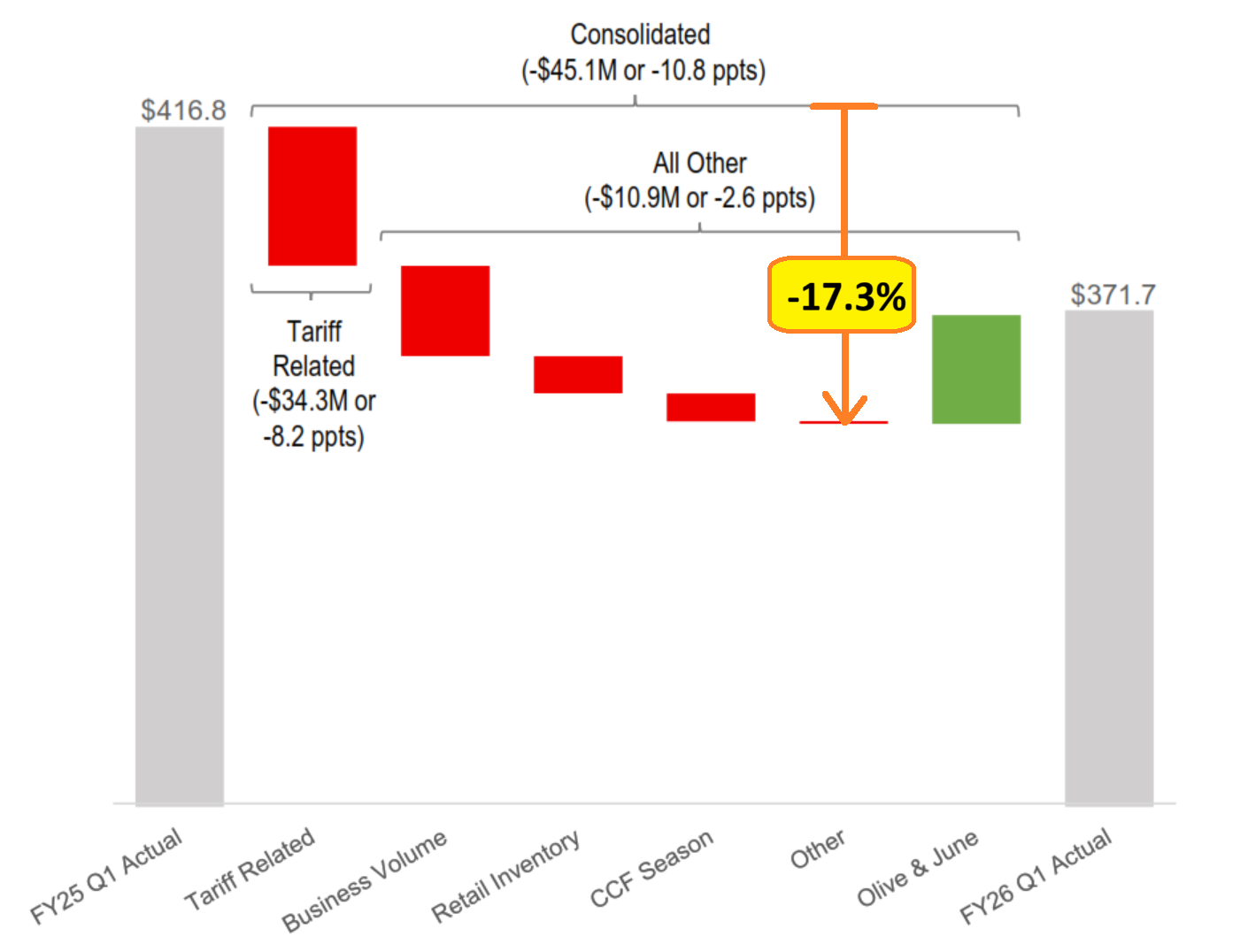

Consumer Weakness and Tariff Pressures: Inside $HELE’s Latest Results

Yesterday brought the first quarterly earnings release from $HELE (Helen of Troy), and the impact of tariffs was unmistakable. The company reported its 1QFY26 results[*], and the numbers were sobering. Excluding the effect of its recent acquisition, sales declined 17.3% year-over-year (see picture below).

Helen of Troy markets a range of consumer goods through brands you likely recognize. In their Home & Outdoor segment, they own OXO, Osprey, and Hydro Flask. In Beauty & Wellness, they own or have the rights to brands such as Revlon, Honeywell, Vicks, Braun, Olive & June, and others. If you’re curious, you can browse their products here.

What stands out from the report is the company’s ability to pinpoint sales lost directly to tariffs. Some clients deliberately held off on orders, hoping to ride out the current tariff environment and replenish inventory later—ideally at a lower tariff rate, but without sacrificing sales in the meantime.

Not all of the sales decline could be tied to specific customer actions. The company also classified portions as “business volume” losses and “retail inventory” adjustments. Regardless of the breakdown, this marks the fourth consecutive year of declining sales at $HELE. The first two years could be chalked up to post-pandemic normalization. Still, the last two years reinforce a trend I’ve highlighted here before: American consumers are simply not consuming at pre-pandemic levels.

Even if, over time, imported products are replaced by domestic alternatives, the initial effect is predictably negative. For $HELE, it’s highly unlikely their contract manufacturers will relocate production to the US—labor costs are simply too high for US-based factories to compete with Asian manufacturers, even if tariffs reach triple digits.

It remains to be seen how the shifting US tariff landscape will ultimately shape the broader economy.

[*] Their fiscal quarters end in February, May, August, and November.

The Surprising Upside for $CHH (Choice Hotels) in a Soft Market

I’ve just finished updating my analysis on $CHH (Choice Hotels). The company franchises a wide range of hotel brands—including Comfort (Inn, Suites), Quality Inn, Econo Lodge, Rodeway Inn, Sleep Inn, Country Inn & Suites, Ascend Hotel Collection, Clarion (including Clarion Pointe), WoodSpring Suites, and MainStay Suites. These brands span the spectrum from economy to upscale. Altogether, CHH has nearly 8,000 properties, representing over 650,000 rooms.

On the most recent conference call, management was asked about the softness in leisure and lower-end chain scales—an outcome that runs counter to expectations of “trade-down” in a weaker economy. The CEO’s response was telling: in uncertain economic periods, Choice’s established brands with strong name recognition tend to attract more independent hotels looking to join a larger system.

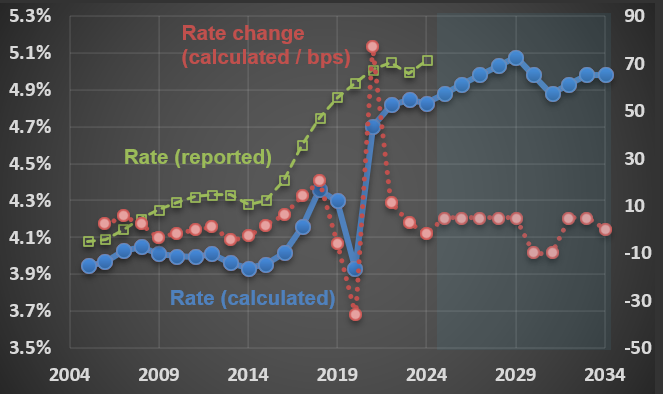

To illustrate just how much “economic times”—something no company can control—can affect business (sometimes positively), take a look at the first chart below. The blue line shows the actual royalty rate that CHH charges hotel owners to be part of its system. While Choice Hotels was already working to increase fees, it was able to raise them by about 25% (from ~4% to ~5%) almost instantly during the pandemic.

What stands out is that this increase in fees happened during a period when both average occupancy and ADR (Average Daily Rate) were lower than pre-pandemic levels (all figures in USD are adjusted for inflation). These two ratios combine to produce RevPAR (Revenue Per Available Room*), which remains below pre-pandemic years—nearly 20% lower in 2024 compared to 2017 (the peak year over the past two decades).

In other words, it wasn’t a boom in business that drove thousands of independent hotels to join the Choice system. Rather, Choice Hotels’ brands are strong enough that, even with significantly higher royalty fees than before the pandemic, the net return for hotel owners is still attractive.

[*] RevPAR = Occupancy x ADR

How Government Incentives Are Shaping $WM’s Capital Decisions

Today, I’m deep into my analysis of $WM (Waste Management). On any given day, the company’s teams collect waste and recyclables from 21 million homes and businesses, operate fleets along set routes, and move materials to processing or disposal facilities.

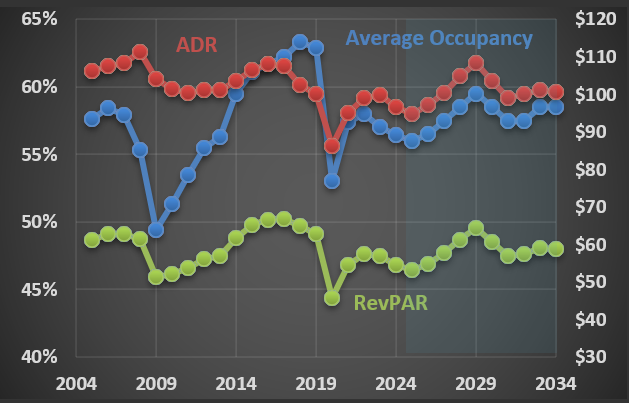

As I incorporate insights from the latest Investor Day, I’m reminded how influential—and sometimes questionable—regulations can be from an economic perspective. Back in 2016, nearly a decade ago, I added a note on the CapEx (capital expenditure) section of the WM’s model: “Since 2005, organic growth has been mostly negative—therefore, I will assume no Growth CapEx; this means that recent CapEx is an excellent estimate of necessary Maintenance CapEx.”

That forecast primarily held. For years, most of Waste Management’s CapEx focused on maintaining existing operations. If you look at the first chart below, you’ll see that CapEx was, until 2022, dominated by red (Maintenance CapEx), with only a modest amount in blue (Growth CapEx). But in 2022, there’s a clear uptick in growth investment. What changed?

The answer lies in the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), which introduced a range of incentives for renewable energy. RNIs (Renewable Identification Numbers) and LCFS (Low Carbon Fuel Standard) credits now make producing RNG (Renewable Natural Gas) from landfills “economically” attractive.

Why the quotation marks around “economically”? If you dig into the actual costs of producing RNG from landfills, estimates range from $ 7.50 to $ 21.50 per MMBtu. For context, take a look at the second figure below, which shows the price of natural gas in the U.S. over the last 20 years. The green line marks the lowest cost to produce RNG—notice how it compares to market prices. In other words, without incentives, RNG production is not profitable.

The key risk for Waste Management is that if government incentives are withdrawn, these new assets could quickly become uneconomical, even if we treat the initial CapEx as a sunk cost. Time will tell whether this was a prudent long-term investment.

The Magnificent-7 and the Rest: What History Suggests for Investors

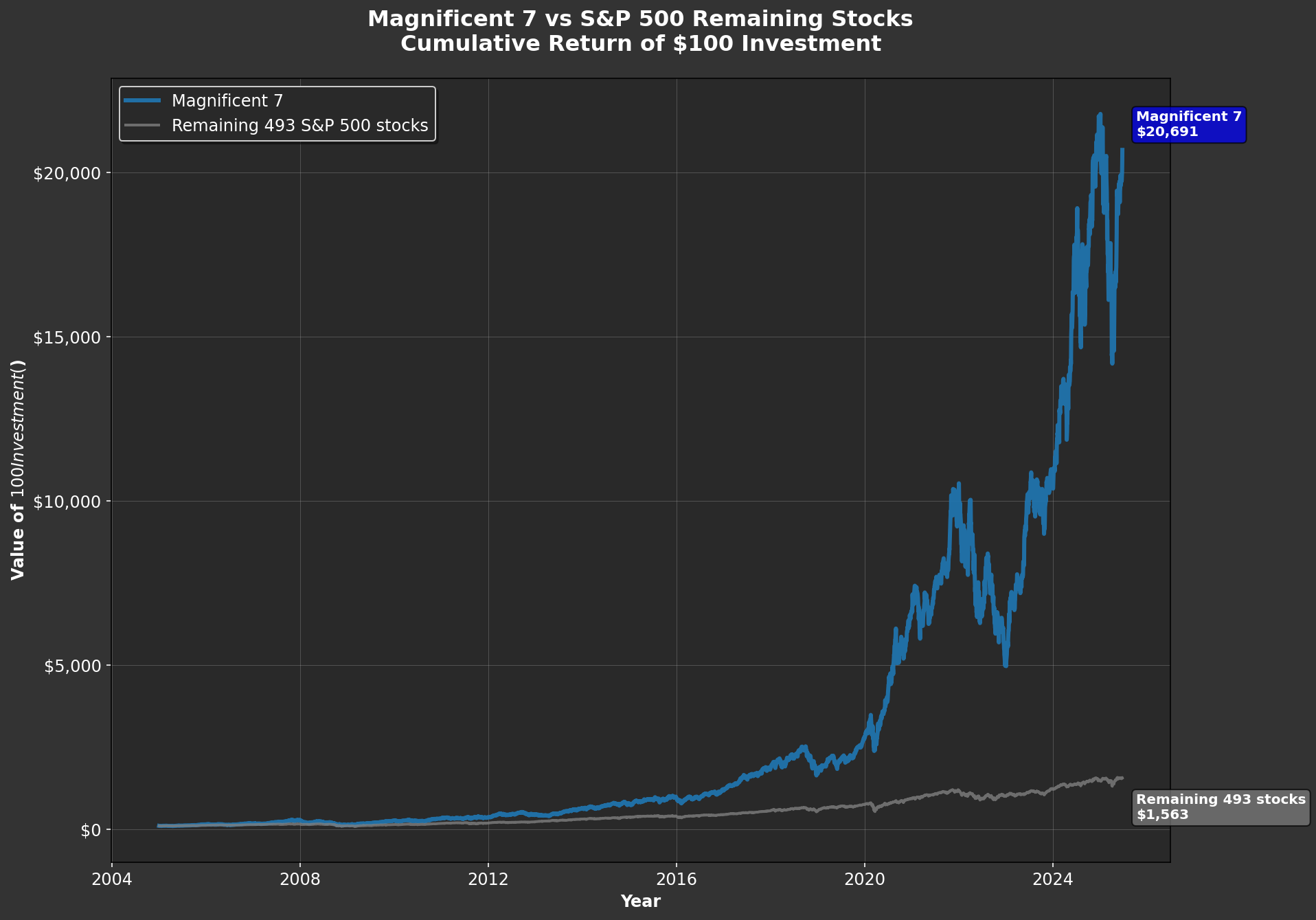

As some broad indexes (like the Nasdaq and S&P 500) approach all-time highs, I wanted to share a few thoughts on what’s driving these moves. We’re living through a highly unusual period, where a small group of companies have achieved extraordinary scale, profitability, and market valuations. I’m referring to the Magnificent-7 ($AAPL, $MSFT, $GOOGL, $AMZN, $NVDA, $META, and $TSLA), whose performance has had an outsized impact on the indexes mentioned above.

The first chart below highlights just how significant this has been: it shows the cumulative performance of the Magnificent-7 compared to the other 493 companies currently in the S&P 500(*). The gap is remarkable—since 2005, the Magnificent-7 have outperformed the rest by a factor of 13.7. It’s easy to forget how difficult it would have been to predict, twenty years ago, just how dominant these businesses would become. But what about more recently? Take a look at the second chart, which starts the clock in January 2020. Even over this shorter period, the Magnificent-7 outpaced the rest of the S&P 500 by 3.7 times—surpassing their outperformance during the entire prior 15 years (which was 3.6 times).

I’m not here to tell you whether these companies are overvalued—that’s outside my “Circle of Competence,” and I have no stake in whether their valuations are justified. However, I do worry about the potential consequences if their valuations were to come under pressure. The best parallel I can draw is with what happened after the Internet Bubble burst in 2000.

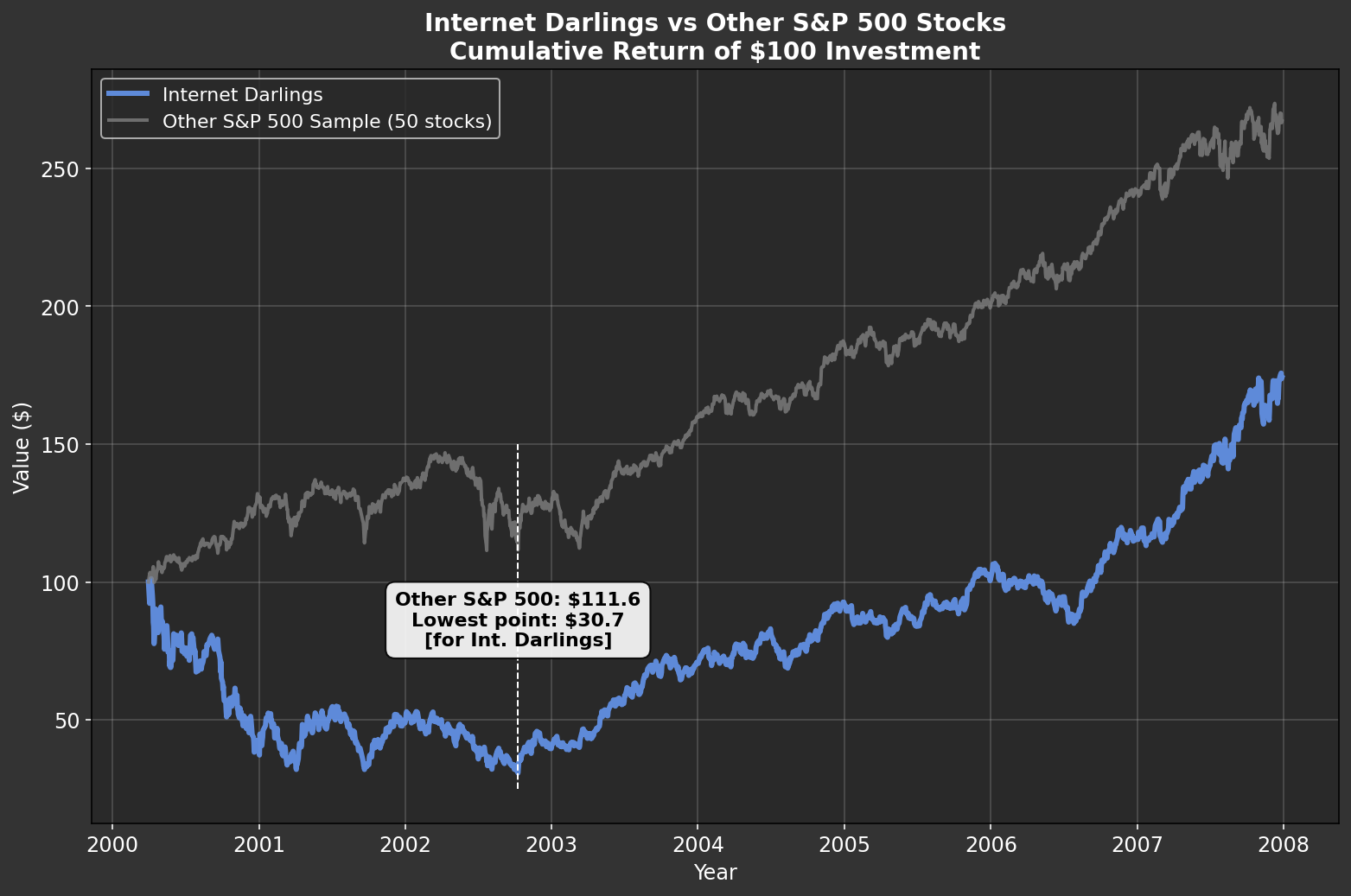

The third chart below compares two groups. In blue, the “Internet Darlings”: Amazon, eBay, Microsoft, Cisco Systems, Intel, Oracle, Apple, Qualcomm, Adobe, and Priceline (now Booking Holdings). These are all survivors—I’ve excluded any high-flyers that later imploded, which actually improves the group’s performance. The grey line represents 50 companies that could be considered “value names”—think Coca-Cola, Pepsi, Home Depot, Walmart, Pfizer, and so on. I’ve even included some companies in this group that were expensive at the time (as I discussed in a previous post here), so the comparison is not stacked in their favor.

The results are striking. Over the next two and a half years, the Internet Darlings declined by 70%. Meanwhile, holders of the more “mundane” companies saw their investments appreciate by 11%—not spectacular, but certainly preferable to being left with only 30% of your capital. Will history repeat itself? There’s no way to know for sure. Still, I find some comfort in knowing that my investments today are much more closely aligned with the kinds of companies represented by the gray line in the early 2000s.

(*) All calculations are performed using Python—let me know if you’d like a copy of the code. All figures include dividends.

$FLS and the New Oil Order: Why Middle East Turmoil Might Have a Smaller Impact Than Before

As part of my ongoing analysis of $FLS (Flowserve Corporation), a global leader in the design, manufacture, and service of flow control systems—including pumps, valves, seals, automation, and related services for the oil and gas, chemical, power, and water industries—it’s essential to understand the broader energy market context in which the company operates.

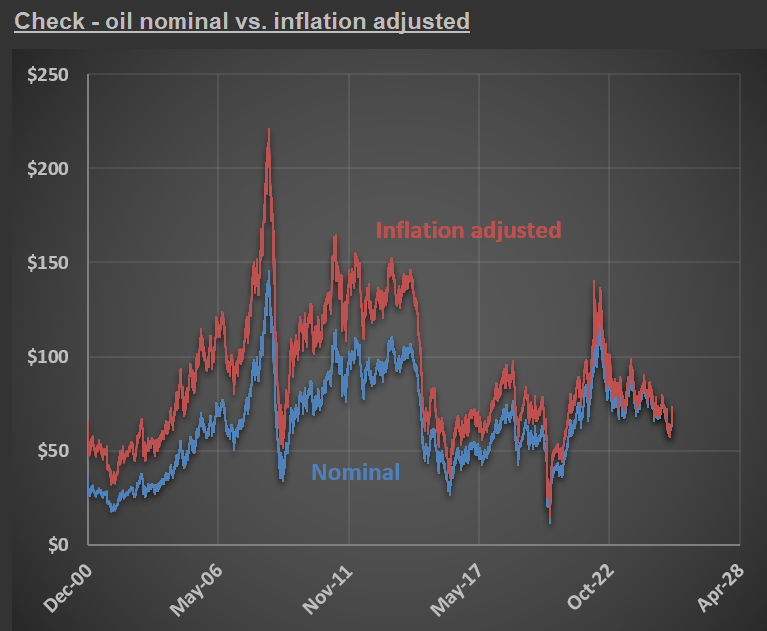

The first chart compares the price of oil in both nominal terms (blue line) and inflation-adjusted terms (red line). A striking feature of the chart is the dramatic spike in oil prices during mid-2008, when the inflation-adjusted price of oil exceeded $220 per barrel. In contrast, current oil prices are significantly lower, both in nominal and real terms, highlighting how much less expensive oil is today compared to that historic peak.

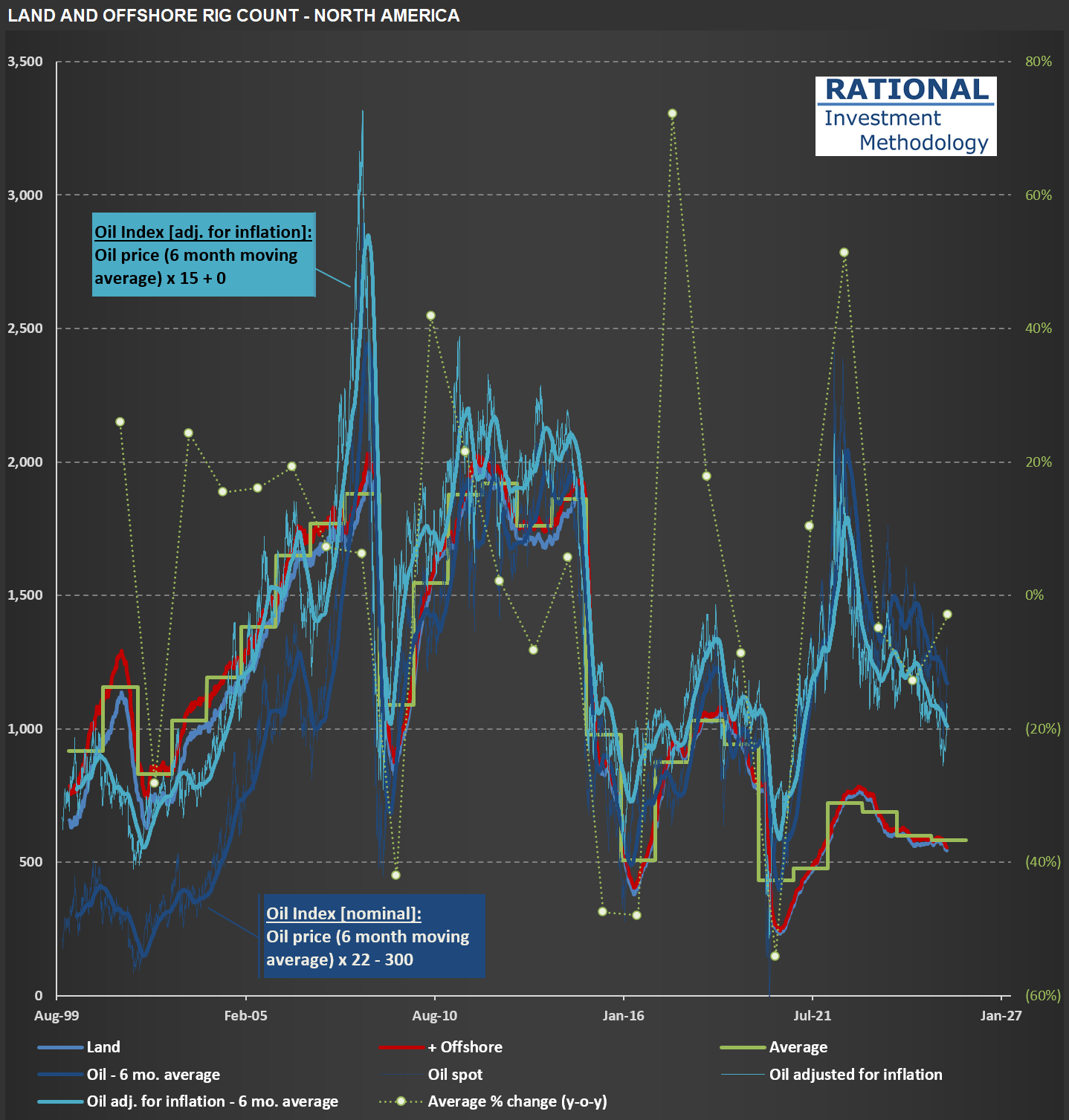

Turning to the second chart, we see the evolution of land and offshore rig counts in North America. Historically, geopolitical tensions in the Middle East have had a pronounced impact on the US economy, mainly due to the country’s reliance on imported oil. However, the shale revolution has fundamentally altered this dynamic. The 2000s saw a substantial increase in the number of rigs operating in the US, coinciding with significant advancements in hydraulic fracturing (fracking) technology. This surge in domestic production has reduced the US economy’s vulnerability to external oil shocks and has been a key driver of energy independence.

Interestingly, the most recent spike in oil prices did not result in a proportional increase in rig count, as seen in previous cycles. This could suggest several things:

- Higher Break-Even Prices: Many fracking wells now require higher oil prices to be economically viable, as the most accessible reserves were tapped during the initial fracking boom.

- Productive Well Inventory: A substantial inventory of productive wells may still exist, reducing the immediate need for new drilling activity.

- Industry Caution: Operators may be exercising greater capital discipline, focusing on maximizing returns from existing assets rather than aggressively expanding capacity.

For Flowserve, these dynamics are highly relevant. The company’s growth prospects are impacted by capital spending cycles in the oil and gas sector, which are influenced by both oil prices and geopolitical stability. While current Middle East tensions have injected fresh volatility into the market, the structural resilience provided by U.S. shale production and a more cautious approach to new drilling may temper the impact on equipment demand in the near term.

Consumer Confidence and RV Sales: Insights from Thor Industries ($THO)

I just finished updating my analysis of $THO (Thor Industries), the largest manufacturer of RVs (Recreational Vehicles) in the US. The U.S. RV market is dominated by a few major players, often called the “Big 3”: Thor, Forest River (a Berkshire Hathaway company), and Winnebago, an iconic name in the RV world.

Thor’s management shared in their latest earnings release that retail demand has generally aligned with expectations, despite some challenges in the first half of FY25 (August 2024 to January 2025). While there was improvement in the second half, it was less than initially anticipated, prompting a revision of prior guidance. The slight increase in consumer confidence in May 2025 is a positive sign for retail demand through the end of FY25 (July 2025). However, aggressive tariff policies could weigh on demand in the latter half of the calendar year if their impact on Average Sales Prices (ASPs) is not effectively managed industry-wide. They also expect the first quarter of fiscal 2026 (June to August 2025) to be challenging.

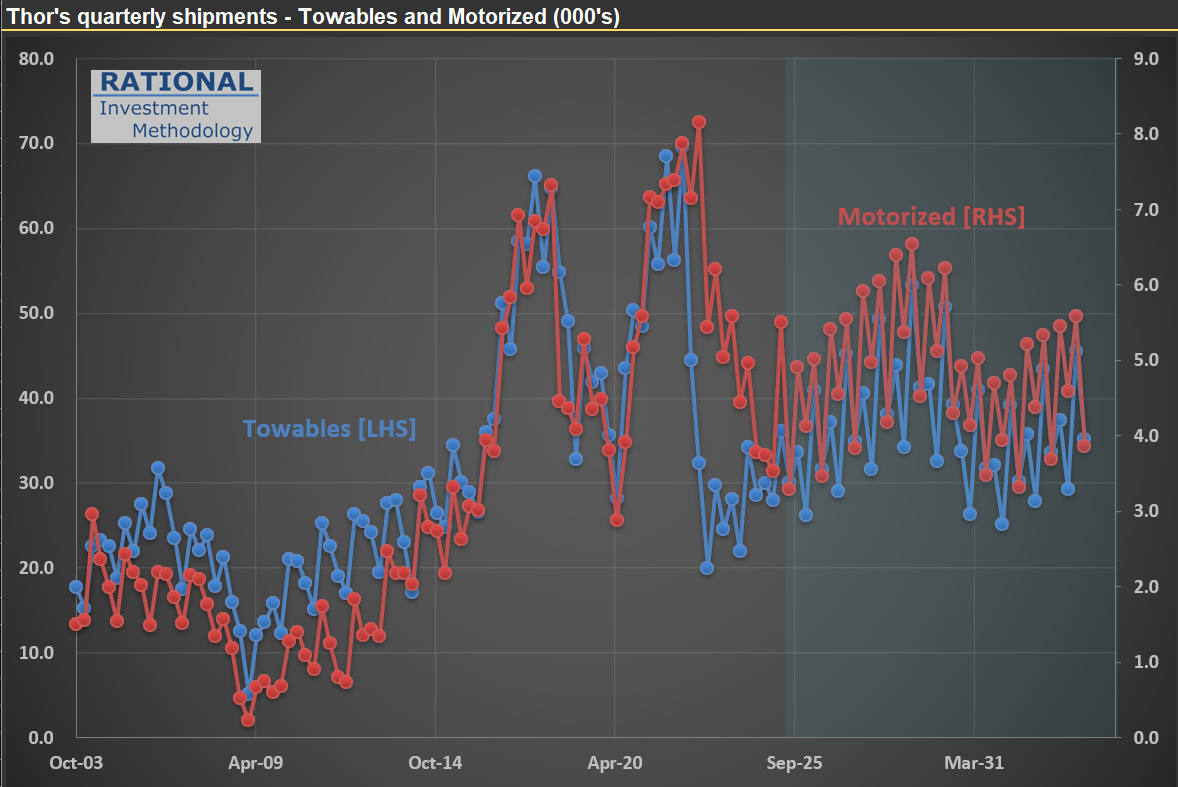

The main reason for this cautious outlook? Tariff uncertainties. Now, consider that Thor has already been navigating significant fluctuations in demand—see the picture below. The blue line illustrates quarterly deliveries in their “towables” segment, the company’s largest. Imagine running a production line that must handle between 20,000 and 70,000 units every three months, without knowing in advance when demand will be strong or weak.

Thor sells highly discretionary products—you don’t really need an RV! Because of this, their sales levels serve as a strong indicator of real consumer confidence. I’ll be watching their numbers closely as we move through what remains an unnecessarily volatile economic and operational environment.